Spring Batch Introduction

Many applications within the enterprise domain require bulk processing to perform business operations in mission critical environments. These business operations include:

-

Automated, complex processing of large volumes of information that is most efficiently processed without user interaction. These operations typically include time-based events (such as month-end calculations, notices, or correspondence).

-

Periodic application of complex business rules processed repetitively across very large data sets (for example, insurance benefit determination or rate adjustments).

-

Integration of information that is received from internal and external systems that typically requires formatting, validation, and processing in a transactional manner into the system of record. Batch processing is used to process billions of transactions every day for enterprises.

Spring Batch is a lightweight, comprehensive batch framework designed to enable the development of robust batch applications vital for the daily operations of enterprise systems. Spring Batch builds upon the characteristics of the Spring Framework that people have come to expect (productivity, POJO-based development approach, and general ease of use), while making it easy for developers to access and leverage more advance enterprise services when necessary. Spring Batch is not a scheduling framework. There are many good enterprise schedulers (such as Quartz, Tivoli, Control-M, etc.) available in both the commercial and open source spaces. It is intended to work in conjunction with a scheduler, not replace a scheduler.

Spring Batch provides reusable functions that are essential in processing large volumes of records, including logging/tracing, transaction management, job processing statistics, job restart, skip, and resource management. It also provides more advanced technical services and features that enable extremely high-volume and high performance batch jobs through optimization and partitioning techniques. Spring Batch can be used in both simple use cases (such as reading a file into a database or running a stored procedure) as well as complex, high volume use cases (such as moving high volumes of data between databases, transforming it, and so on). High-volume batch jobs can leverage the framework in a highly scalable manner to process significant volumes of information.

Background

While open source software projects and associated communities have focused greater attention on web-based and microservices-based architecture frameworks, there has been a notable lack of focus on reusable architecture frameworks to accommodate Java-based batch processing needs, despite continued needs to handle such processing within enterprise IT environments. The lack of a standard, reusable batch architecture has resulted in the proliferation of many one-off, in-house solutions developed within client enterprise IT functions.

SpringSource (now Pivotal) and Accenture collaborated to change this. Accenture’s hands-on industry and technical experience in implementing batch architectures, SpringSource’s depth of technical experience, and Spring’s proven programming model together made a natural and powerful partnership to create high-quality, market-relevant software aimed at filling an important gap in enterprise Java. Both companies worked with a number of clients who were solving similar problems by developing Spring-based batch architecture solutions. This provided some useful additional detail and real-life constraints that helped to ensure the solution can be applied to the real-world problems posed by clients.

Accenture contributed previously proprietary batch processing architecture frameworks to the Spring Batch project, along with committer resources to drive support, enhancements, and the existing feature set. Accenture’s contribution was based upon decades of experience in building batch architectures with the last several generations of platforms: COBOL/Mainframe, C++/Unix, and now Java/anywhere.

The collaborative effort between Accenture and SpringSource aimed to promote the standardization of software processing approaches, frameworks, and tools that can be consistently leveraged by enterprise users when creating batch applications. Companies and government agencies desiring to deliver standard, proven solutions to their enterprise IT environments can benefit from Spring Batch.

Usage Scenarios

A typical batch program generally:

-

Reads a large number of records from a database, file, or queue.

-

Processes the data in some fashion.

-

Writes back data in a modified form.

Spring Batch automates this basic batch iteration, providing the capability to process similar transactions as a set, typically in an offline environment without any user interaction. Batch jobs are part of most IT projects, and Spring Batch is the only open source framework that provides a robust, enterprise-scale solution.

Business Scenarios

-

Commit batch process periodically

-

Concurrent batch processing: parallel processing of a job

-

Staged, enterprise message-driven processing

-

Massively parallel batch processing

-

Manual or scheduled restart after failure

-

Sequential processing of dependent steps (with extensions to workflow-driven batches)

-

Partial processing: skip records (for example, on rollback)

-

Whole-batch transaction, for cases with a small batch size or existing stored procedures/scripts

Technical Objectives

-

Batch developers use the Spring programming model: Concentrate on business logic and let the framework take care of infrastructure.

-

Clear separation of concerns between the infrastructure, the batch execution environment, and the batch application.

-

Provide common, core execution services as interfaces that all projects can implement.

-

Provide simple and default implementations of the core execution interfaces that can be used 'out of the box'.

-

Easy to configure, customize, and extend services, by leveraging the spring framework in all layers.

-

All existing core services should be easy to replace or extend, without any impact to the infrastructure layer.

-

Provide a simple deployment model, with the architecture JARs completely separate from the application, built using Maven.

Spring Batch Architecture

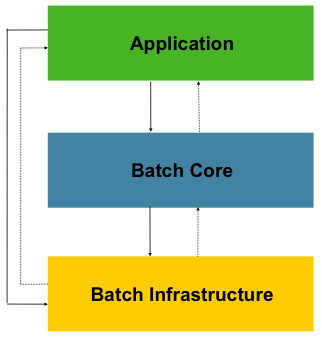

Spring Batch is designed with extensibility and a diverse group of end users in mind. The figure below shows the layered architecture that supports the extensibility and ease of use for end-user developers.

This layered architecture highlights three major high-level components: Application,

Core, and Infrastructure. The application contains all batch jobs and custom code written

by developers using Spring Batch. The Batch Core contains the core runtime classes

necessary to launch and control a batch job. It includes implementations for

JobLauncher, Job, and Step. Both Application and Core are built on top of a common

infrastructure. This infrastructure contains common readers and writers and services

(such as the RetryTemplate), which are used both by application developers(readers and

writers, such as ItemReader and ItemWriter) and the core framework itself (retry,

which is its own library).

General Batch Principles and Guidelines

The following key principles, guidelines, and general considerations should be considered when building a batch solution.

-

Remember that a batch architecture typically affects on-line architecture and vice versa. Design with both architectures and environments in mind using common building blocks when possible.

-

Simplify as much as possible and avoid building complex logical structures in single batch applications.

-

Keep the processing and storage of data physically close together (in other words, keep your data where your processing occurs).

-

Minimize system resource use, especially I/O. Perform as many operations as possible in internal memory.

-

Review application I/O (analyze SQL statements) to ensure that unnecessary physical I/O is avoided. In particular, the following four common flaws need to be looked for:

-

Reading data for every transaction when the data could be read once and cached or kept in the working storage.

-

Rereading data for a transaction where the data was read earlier in the same transaction.

-

Causing unnecessary table or index scans.

-

Not specifying key values in the WHERE clause of an SQL statement.

-

-

Do not do things twice in a batch run. For instance, if you need data summarization for reporting purposes, you should (if possible) increment stored totals when data is being initially processed, so your reporting application does not have to reprocess the same data.

-

Allocate enough memory at the beginning of a batch application to avoid time-consuming reallocation during the process.

-

Always assume the worst with regard to data integrity. Insert adequate checks and record validation to maintain data integrity.

-

Implement checksums for internal validation where possible. For example, flat files should have a trailer record telling the total of records in the file and an aggregate of the key fields.

-

Plan and execute stress tests as early as possible in a production-like environment with realistic data volumes.

-

In large batch systems, backups can be challenging, especially if the system is running concurrent with on-line on a 24-7 basis. Database backups are typically well taken care of in the on-line design, but file backups should be considered to be just as important. If the system depends on flat files, file backup procedures should not only be in place and documented but be regularly tested as well.

Batch Processing Strategies

To help design and implement batch systems, basic batch application building blocks and patterns should be provided to the designers and programmers in the form of sample structure charts and code shells. When starting to design a batch job, the business logic should be decomposed into a series of steps that can be implemented using the following standard building blocks:

-

Conversion Applications: For each type of file supplied by or generated to an external system, a conversion application must be created to convert the transaction records supplied into a standard format required for processing. This type of batch application can partly or entirely consist of translation utility modules (see Basic Batch Services).

-

Validation Applications: Validation applications ensure that all input/output records are correct and consistent. Validation is typically based on file headers and trailers, checksums and validation algorithms, and record level cross-checks.

-

Extract Applications: An application that reads a set of records from a database or input file, selects records based on predefined rules, and writes the records to an output file.

-

Extract/Update Applications: An application that reads records from a database or an input file and makes changes to a database or an output file driven by the data found in each input record.

-

Processing and Updating Applications: An application that performs processing on input transactions from an extract or a validation application. The processing usually involves reading a database to obtain data required for processing, potentially updating the database and creating records for output processing.

-

Output/Format Applications: Applications that read an input file, restructure data from this record according to a standard format, and produce an output file for printing or transmission to another program or system.

Additionally, a basic application shell should be provided for business logic that cannot be built using the previously mentioned building blocks.

In addition to the main building blocks, each application may use one or more of standard utility steps, such as:

-

Sort: A program that reads an input file and produces an output file where records have been re-sequenced according to a sort key field in the records. Sorts are usually performed by standard system utilities.

-

Split: A program that reads a single input file and writes each record to one of several output files based on a field value. Splits can be tailored or performed by parameter-driven standard system utilities.

-

Merge: A program that reads records from multiple input files and produces one output file with combined data from the input files. Merges can be tailored or performed by parameter-driven standard system utilities.

Batch applications can additionally be categorized by their input source:

-

Database-driven applications are driven by rows or values retrieved from the database.

-

File-driven applications are driven by records or values retrieved from a file.

-

Message-driven applications are driven by messages retrieved from a message queue.

The foundation of any batch system is the processing strategy. Factors affecting the selection of the strategy include: estimated batch system volume, concurrency with on-line systems or with other batch systems, available batch windows. (Note that, with more enterprises wanting to be up and running 24x7, clear batch windows are disappearing).

Typical processing options for batch are (in increasing order of implementation complexity):

-

Normal processing during a batch window in off-line mode.

-

Concurrent batch or on-line processing.

-

Parallel processing of many different batch runs or jobs at the same time.

-

Partitioning (processing of many instances of the same job at the same time).

-

A combination of the preceding options.

Some or all of these options may be supported by a commercial scheduler.

The following section discusses these processing options in more detail. It is important to notice that, as a rule of thumb, the commit and locking strategy adopted by batch processes depends on the type of processing performed and that the on-line locking strategy should also use the same principles. Therefore, the batch architecture cannot be simply an afterthought when designing an overall architecture.

The locking strategy can be to use only normal database locks or to implement an additional custom locking service in the architecture. The locking service would track database locking (for example, by storing the necessary information in a dedicated db-table) and give or deny permissions to the application programs requesting a db operation. Retry logic could also be implemented by this architecture to avoid aborting a batch job in case of a lock situation.

1. Normal processing in a batch window For simple batch processes running in a separate batch window where the data being updated is not required by on-line users or other batch processes, concurrency is not an issue and a single commit can be done at the end of the batch run.

In most cases, a more robust approach is more appropriate. Keep in mind that batch systems have a tendency to grow as time goes by, both in terms of complexity and the data volumes they handle. If no locking strategy is in place and the system still relies on a single commit point, modifying the batch programs can be painful. Therefore, even with the simplest batch systems, consider the need for commit logic for restart-recovery options as well as the information concerning the more complex cases described later in this section.

2. Concurrent batch or on-line processing Batch applications processing data that can be simultaneously updated by on-line users should not lock any data (either in the database or in files) which could be required by on-line users for more than a few seconds. Also, updates should be committed to the database at the end of every few transactions. This minimizes the portion of data that is unavailable to other processes and the elapsed time the data is unavailable.

Another option to minimize physical locking is to have logical row-level locking implemented with either an Optimistic Locking Pattern or a Pessimistic Locking Pattern.

-

Optimistic locking assumes a low likelihood of record contention. It typically means inserting a timestamp column in each database table used concurrently by both batch and on-line processing. When an application fetches a row for processing, it also fetches the timestamp. As the application then tries to update the processed row, the update uses the original timestamp in the WHERE clause. If the timestamp matches, the data and the timestamp are updated. If the timestamp does not match, this indicates that another application has updated the same row between the fetch and the update attempt. Therefore, the update cannot be performed.

-

Pessimistic locking is any locking strategy that assumes there is a high likelihood of record contention and therefore either a physical or logical lock needs to be obtained at retrieval time. One type of pessimistic logical locking uses a dedicated lock-column in the database table. When an application retrieves the row for update, it sets a flag in the lock column. With the flag in place, other applications attempting to retrieve the same row logically fail. When the application that sets the flag updates the row, it also clears the flag, enabling the row to be retrieved by other applications. Please note that the integrity of data must be maintained also between the initial fetch and the setting of the flag, for example by using db locks (such as

SELECT FOR UPDATE). Note also that this method suffers from the same downside as physical locking except that it is somewhat easier to manage building a time-out mechanism that gets the lock released if the user goes to lunch while the record is locked.

These patterns are not necessarily suitable for batch processing, but they might be used for concurrent batch and on-line processing (such as in cases where the database does not support row-level locking). As a general rule, optimistic locking is more suitable for on-line applications, while pessimistic locking is more suitable for batch applications. Whenever logical locking is used, the same scheme must be used for all applications accessing data entities protected by logical locks.

Note that both of these solutions only address locking a single record. Often, we may need to lock a logically related group of records. With physical locks, you have to manage these very carefully in order to avoid potential deadlocks. With logical locks, it is usually best to build a logical lock manager that understands the logical record groups you want to protect and that can ensure that locks are coherent and non-deadlocking. This logical lock manager usually uses its own tables for lock management, contention reporting, time-out mechanism, and other concerns.

3. Parallel Processing Parallel processing allows multiple batch runs or jobs to run in parallel to minimize the total elapsed batch processing time. This is not a problem as long as the jobs are not sharing the same files, db-tables, or index spaces. If they do, this service should be implemented using partitioned data. Another option is to build an architecture module for maintaining interdependencies by using a control table. A control table should contain a row for each shared resource and whether it is in use by an application or not. The batch architecture or the application in a parallel job would then retrieve information from that table to determine if it can get access to the resource it needs or not.

If the data access is not a problem, parallel processing can be implemented through the use of additional threads to process in parallel. In the mainframe environment, parallel job classes have traditionally been used, in order to ensure adequate CPU time for all the processes. Regardless, the solution has to be robust enough to ensure time slices for all the running processes.

Other key issues in parallel processing include load balancing and the availability of general system resources such as files, database buffer pools, and so on. Also note that the control table itself can easily become a critical resource.

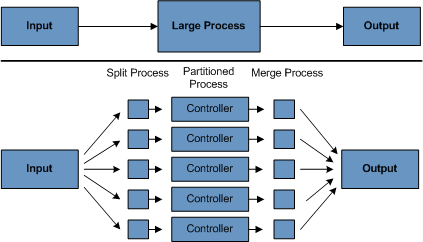

4. Partitioning Using partitioning allows multiple versions of large batch applications to run concurrently. The purpose of this is to reduce the elapsed time required to process long batch jobs. Processes that can be successfully partitioned are those where the input file can be split and/or the main database tables partitioned to allow the application to run against different sets of data.

In addition, processes which are partitioned must be designed to only process their assigned data set. A partitioning architecture has to be closely tied to the database design and the database partitioning strategy. Note that database partitioning does not necessarily mean physical partitioning of the database, although in most cases this is advisable. The following picture illustrates the partitioning approach:

The architecture should be flexible enough to allow dynamic configuration of the number of partitions. Both automatic and user controlled configuration should be considered. Automatic configuration may be based on parameters such as the input file size and the number of input records.

4.1 Partitioning Approaches Selecting a partitioning approach has to be done on a case-by-case basis. The following list describes some of the possible partitioning approaches:

1. Fixed and Even Break-Up of Record Set

This involves breaking the input record set into an even number of portions (for example, 10, where each portion has exactly 1/10th of the entire record set). Each portion is then processed by one instance of the batch/extract application.

In order to use this approach, preprocessing is required to split the record set up. The result of this split will be a lower and upper bound placement number which can be used as input to the batch/extract application in order to restrict its processing to only its portion.

Preprocessing could be a large overhead, as it has to calculate and determine the bounds of each portion of the record set.

2. Break up by a Key Column

This involves breaking up the input record set by a key column, such as a location code, and assigning data from each key to a batch instance. In order to achieve this, column values can be either:

-

Assigned to a batch instance by a partitioning table (described later in this section).

-

Assigned to a batch instance by a portion of the value (such as 0000-0999, 1000 - 1999, and so on).

Under option 1, adding new values means a manual reconfiguration of the batch/extract to ensure that the new value is added to a particular instance.

Under option 2, this ensures that all values are covered via an instance of the batch job. However, the number of values processed by one instance is dependent on the distribution of column values (there may be a large number of locations in the 0000-0999 range, and few in the 1000-1999 range). Under this option, the data range should be designed with partitioning in mind.

Under both options, the optimal even distribution of records to batch instances cannot be realized. There is no dynamic configuration of the number of batch instances used.

3. Breakup by Views

This approach is basically breakup by a key column but on the database level. It involves breaking up the record set into views. These views are used by each instance of the batch application during its processing. The breakup is done by grouping the data.

With this option, each instance of a batch application has to be configured to hit a particular view (instead of the master table). Also, with the addition of new data values, this new group of data has to be included into a view. There is no dynamic configuration capability, as a change in the number of instances results in a change to the views.

4. Addition of a Processing Indicator

This involves the addition of a new column to the input table, which acts as an indicator. As a preprocessing step, all indicators are marked as being non-processed. During the record fetch stage of the batch application, records are read on the condition that that record is marked as being non-processed, and once they are read (with lock), they are marked as being in processing. When that record is completed, the indicator is updated to either complete or error. Many instances of a batch application can be started without a change, as the additional column ensures that a record is only processed once.

With this option, I/O on the table increases dynamically. In the case of an updating batch application, this impact is reduced, as a write must occur anyway.

5. Extract Table to a Flat File

This involves the extraction of the table into a file. This file can then be split into multiple segments and used as input to the batch instances.

With this option, the additional overhead of extracting the table into a file and splitting it may cancel out the effect of multi-partitioning. Dynamic configuration can be achieved by changing the file splitting script.

6. Use of a Hashing Column

This scheme involves the addition of a hash column (key/index) to the database tables used to retrieve the driver record. This hash column has an indicator to determine which instance of the batch application processes this particular row. For example, if there are three batch instances to be started, then an indicator of 'A' marks a row for processing by instance 1, an indicator of 'B' marks a row for processing by instance 2, and an indicator of 'C' marks a row for processing by instance 3.

The procedure used to retrieve the records would then have an additional WHERE clause

to select all rows marked by a particular indicator. The inserts in this table would

involve the addition of the marker field, which would be defaulted to one of the

instances (such as 'A').

A simple batch application would be used to update the indicators, such as to redistribute the load between the different instances. When a sufficiently large number of new rows have been added, this batch can be run (anytime, except in the batch window) to redistribute the new rows to other instances.

Additional instances of the batch application only require the running of the batch application as described in the preceding paragraphs to redistribute the indicators to work with a new number of instances.

4.2 Database and Application Design Principles

An architecture that supports multi-partitioned applications which run against partitioned database tables using the key column approach should include a central partition repository for storing partition parameters. This provides flexibility and ensures maintainability. The repository generally consists of a single table, known as the partition table.

Information stored in the partition table is static and, in general, should be maintained by the DBA. The table should consist of one row of information for each partition of a multi-partitioned application. The table should have columns for Program ID Code, Partition Number (logical ID of the partition), Low Value of the db key column for this partition, and High Value of the db key column for this partition.

On program start-up, the program id and partition number should be passed to the

application from the architecture (specifically, from the Control Processing Tasklet). If

a key column approach is used, these variables are used to read the partition table in

order to determine what range of data the application is to process. In addition the

partition number must be used throughout the processing to:

-

Add to the output files/database updates in order for the merge process to work properly.

-

Report normal processing to the batch log and any errors to the architecture error handler.

4.3 Minimizing Deadlocks

When applications run in parallel or are partitioned, contention in database resources and deadlocks may occur. It is critical that the database design team eliminates potential contention situations as much as possible as part of the database design.

Also, the developers must ensure that the database index tables are designed with deadlock prevention and performance in mind.

Deadlocks or hot spots often occur in administration or architecture tables, such as log tables, control tables, and lock tables. The implications of these should be taken into account as well. A realistic stress test is crucial for identifying the possible bottlenecks in the architecture.

To minimize the impact of conflicts on data, the architecture should provide services such as wait-and-retry intervals when attaching to a database or when encountering a deadlock. This means a built-in mechanism to react to certain database return codes and, instead of issuing an immediate error, waiting a predetermined amount of time and retrying the database operation.

4.4 Parameter Passing and Validation

The partition architecture should be relatively transparent to application developers. The architecture should perform all tasks associated with running the application in a partitioned mode, including:

-

Retrieving partition parameters before application start-up.

-

Validating partition parameters before application start-up.

-

Passing parameters to the application at start-up.

The validation should include checks to ensure that:

-

The application has sufficient partitions to cover the whole data range.

-

There are no gaps between partitions.

If the database is partitioned, some additional validation may be necessary to ensure that a single partition does not span database partitions.

Also, the architecture should take into consideration the consolidation of partitions. Key questions include:

-

Must all the partitions be finished before going into the next job step?

-

What happens if one of the partitions aborts?