Configuring a Step

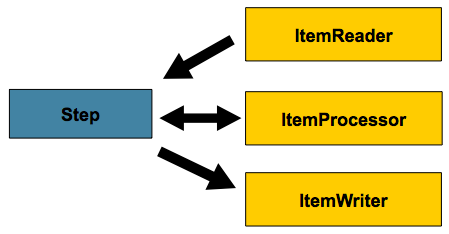

As discussed in the domain chapter, a Step is a

domain object that encapsulates an independent, sequential phase of a batch job and

contains all of the information necessary to define and control the actual batch

processing. This is a necessarily vague description because the contents of any given

Step are at the discretion of the developer writing a Job. A Step can be as simple

or complex as the developer desires. A simple Step might load data from a file into the

database, requiring little or no code (depending upon the implementations used). A more

complex Step might have complicated business rules that are applied as part of the

processing, as the following image shows:

Chunk-oriented Processing

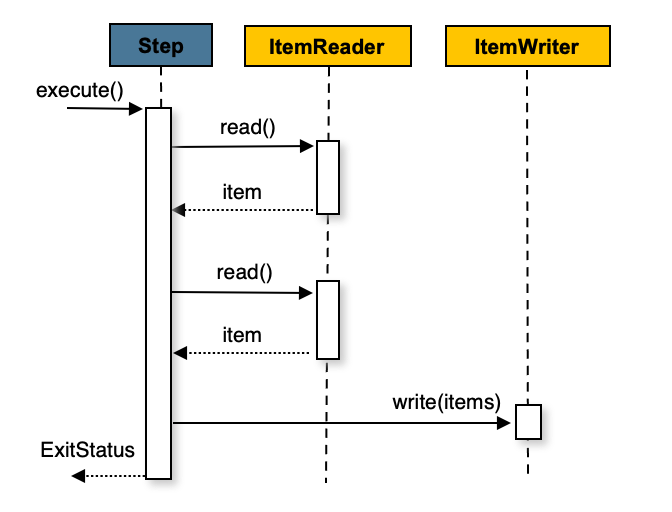

Spring Batch uses a “chunk-oriented” processing style in its most common

implementation. Chunk oriented processing refers to reading the data one at a time and

creating 'chunks' that are written out within a transaction boundary. Once the number of

items read equals the commit interval, the entire chunk is written out by the

ItemWriter, and then the transaction is committed. The following image shows the

process:

The following pseudo code shows the same concepts in a simplified form:

List items = new Arraylist();

for(int i = 0; i < commitInterval; i++){

Object item = itemReader.read();

if (item != null) {

items.add(item);

}

}

itemWriter.write(items);

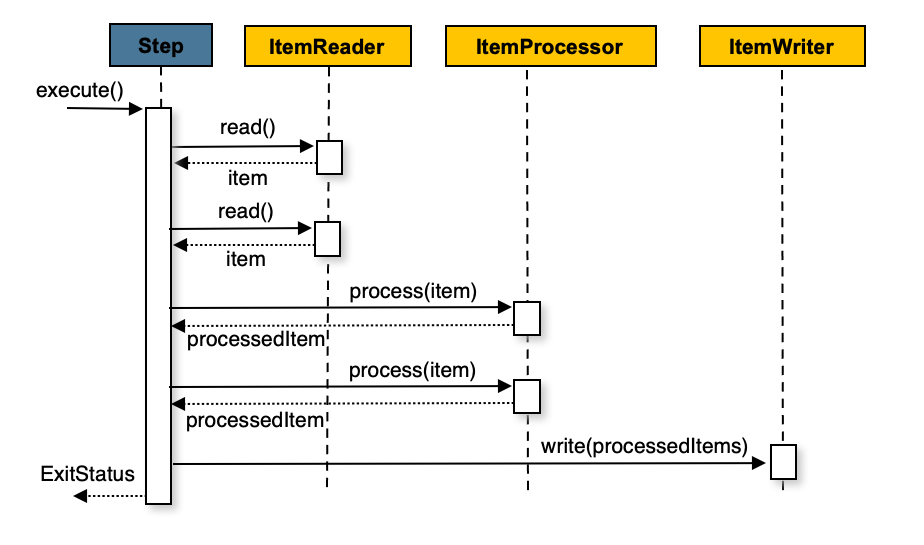

You can also configure a chunk-oriented step with an optional ItemProcessor

to process items before passing them to the ItemWriter. The following image

shows the process when an ItemProcessor is registered in the step:

The following pseudo code shows how this is implemented in a simplified form:

List items = new Arraylist();

for(int i = 0; i < commitInterval; i++){

Object item = itemReader.read();

if (item != null) {

items.add(item);

}

}

List processedItems = new Arraylist();

for(Object item: items){

Object processedItem = itemProcessor.process(item);

if (processedItem != null) {

processedItems.add(processedItem);

}

}

itemWriter.write(processedItems);

For more details about item processors and their use cases, see the Item processing section.

Configuring a Step

Despite the relatively short list of required dependencies for a Step, it is an

extremely complex class that can potentially contain many collaborators.

To ease configuration, you can use the Spring Batch XML namespace, as the following example shows:

<job id="sampleJob" job-repository="jobRepository">

<step id="step1">

<tasklet transaction-manager="transactionManager">

<chunk reader="itemReader" writer="itemWriter" commit-interval="10"/>

</tasklet>

</step>

</job>When using Java configuration, you can use the Spring Batch builders, as the following example shows:

/**

* Note the JobRepository is typically autowired in and not needed to be explicitly

* configured

*/

@Bean

public Job sampleJob(JobRepository jobRepository, Step sampleStep) {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("sampleJob")

.repository(jobRepository)

.start(sampleStep)

.build();

}

/**

* Note the TransactionManager is typically autowired in and not needed to be explicitly

* configured

*/

@Bean

public Step sampleStep(PlatformTransactionManager transactionManager) {

return this.stepBuilderFactory.get("sampleStep")

.transactionManager(transactionManager)

.<String, String>chunk(10)

.reader(itemReader())

.writer(itemWriter())

.build();

}

Inheriting from a Parent Step

If a group of Steps share similar configurations, then it may be helpful to define a

“parent” Step from which the concrete Steps may inherit properties. Similar to class

inheritance in Java, the “child” Step combines its elements and attributes with the

parent’s. The child also overrides any of the parent’s Steps.

In the following example, the Step, concreteStep1, inherits from parentStep. It is

instantiated with itemReader, itemProcessor, itemWriter, startLimit=5, and

allowStartIfComplete=true. Additionally, the commitInterval is 5, since it is

overridden by the concreteStep1 Step, as the following example shows:

<step id="parentStep">

<tasklet allow-start-if-complete="true">

<chunk reader="itemReader" writer="itemWriter" commit-interval="10"/>

</tasklet>

</step>

<step id="concreteStep1" parent="parentStep">

<tasklet start-limit="5">

<chunk processor="itemProcessor" commit-interval="5"/>

</tasklet>

</step>The id attribute is still required on the step within the job element. This is for two

reasons:

-

The

idis used as the step name when persisting theStepExecution. If the same standalone step is referenced in more than one step in the job, an error occurs.

-

When creating job flows, as described later in this chapter, the

nextattribute should refer to the step in the flow, not the standalone step.

Abstract Step

Sometimes, it may be necessary to define a parent Step that is not a complete Step

configuration. If, for instance, the reader, writer, and tasklet attributes are

left off of a Step configuration, then initialization fails. If a parent must be

defined without one or more of these properties, the abstract attribute should be used. An

abstract Step is only extended, never instantiated.

In the following example, the Step (abstractParentStep) would not be instantiated if it

were not declared to be abstract. The Step, (concreteStep2) has itemReader,

itemWriter, and commit-interval=10.

<step id="abstractParentStep" abstract="true">

<tasklet>

<chunk commit-interval="10"/>

</tasklet>

</step>

<step id="concreteStep2" parent="abstractParentStep">

<tasklet>

<chunk reader="itemReader" writer="itemWriter"/>

</tasklet>

</step>Merging Lists

Some of the configurable elements on Steps are lists, such as the <listeners/> element.

If both the parent and child Steps declare a <listeners/> element, the

child’s list overrides the parent’s. To allow a child to add additional

listeners to the list defined by the parent, every list element has a merge attribute.

If the element specifies that merge="true", then the child’s list is combined with the

parent’s instead of overriding it.

In the following example, the Step "concreteStep3", is created with two listeners:

listenerOne and listenerTwo:

<step id="listenersParentStep" abstract="true">

<listeners>

<listener ref="listenerOne"/>

<listeners>

</step>

<step id="concreteStep3" parent="listenersParentStep">

<tasklet>

<chunk reader="itemReader" writer="itemWriter" commit-interval="5"/>

</tasklet>

<listeners merge="true">

<listener ref="listenerTwo"/>

<listeners>

</step>The Commit Interval

As mentioned previously, a step reads in and writes out items, periodically committing

by using the supplied PlatformTransactionManager. With a commit-interval of 1, it

commits after writing each individual item. This is less than ideal in many situations,

since beginning and committing a transaction is expensive. Ideally, it is preferable to

process as many items as possible in each transaction, which is completely dependent upon

the type of data being processed and the resources with which the step is interacting.

For this reason, you can configure the number of items that are processed within a commit.

The following example shows a step whose tasklet has a commit-interval

value of 10 as it would be defined in XML:

<job id="sampleJob">

<step id="step1">

<tasklet>

<chunk reader="itemReader" writer="itemWriter" commit-interval="10"/>

</tasklet>

</step>

</job>The following example shows a step whose tasklet has a commit-interval

value of 10 as it would be defined in Java:

@Bean

public Job sampleJob() {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("sampleJob")

.start(step1())

.build();

}

@Bean

public Step step1() {

return this.stepBuilderFactory.get("step1")

.<String, String>chunk(10)

.reader(itemReader())

.writer(itemWriter())

.build();

}

In the preceding example, 10 items are processed within each transaction. At the

beginning of processing, a transaction is begun. Also, each time read is called on the

ItemReader, a counter is incremented. When it reaches 10, the list of aggregated items

is passed to the ItemWriter, and the transaction is committed.

Configuring a Step for Restart

In the “Configuring and Running a Job” section , restarting a

Job was discussed. Restart has numerous impacts on steps, and, consequently, may

require some specific configuration.

Setting a Start Limit

There are many scenarios where you may want to control the number of times a Step can

be started. For example, you might need to configure a particular Step might so that it

runs only once because it invalidates some resource that must be fixed manually before it can

be run again. This is configurable on the step level, since different steps may have

different requirements. A Step that can be executed only once can exist as part of the

same Job as a Step that can be run infinitely.

The following code fragment shows an example of a start limit configuration in XML:

<step id="step1">

<tasklet start-limit="1">

<chunk reader="itemReader" writer="itemWriter" commit-interval="10"/>

</tasklet>

</step>The following code fragment shows an example of a start limit configuration in Java:

@Bean

public Step step1() {

return this.stepBuilderFactory.get("step1")

.<String, String>chunk(10)

.reader(itemReader())

.writer(itemWriter())

.startLimit(1)

.build();

}

The step shown in the preceding example can be run only once. Attempting to run it again

causes a StartLimitExceededException to be thrown. Note that the default value for the

start-limit is Integer.MAX_VALUE.

Restarting a Completed Step

In the case of a restartable job, there may be one or more steps that should always be

run, regardless of whether or not they were successful the first time. An example might

be a validation step or a Step that cleans up resources before processing. During

normal processing of a restarted job, any step with a status of COMPLETED (meaning it

has already been completed successfully), is skipped. Setting allow-start-if-complete to

true overrides this so that the step always runs.

The following code fragment shows how to define a restartable job in XML:

<step id="step1">

<tasklet allow-start-if-complete="true">

<chunk reader="itemReader" writer="itemWriter" commit-interval="10"/>

</tasklet>

</step>The following code fragment shows how to define a restartable job in Java:

@Bean

public Step step1() {

return this.stepBuilderFactory.get("step1")

.<String, String>chunk(10)

.reader(itemReader())

.writer(itemWriter())

.allowStartIfComplete(true)

.build();

}

Step Restart Configuration Example

The following XML example shows how to configure a job to have steps that can be restarted:

<job id="footballJob" restartable="true">

<step id="playerload" next="gameLoad">

<tasklet>

<chunk reader="playerFileItemReader" writer="playerWriter"

commit-interval="10" />

</tasklet>

</step>

<step id="gameLoad" next="playerSummarization">

<tasklet allow-start-if-complete="true">

<chunk reader="gameFileItemReader" writer="gameWriter"

commit-interval="10"/>

</tasklet>

</step>

<step id="playerSummarization">

<tasklet start-limit="2">

<chunk reader="playerSummarizationSource" writer="summaryWriter"

commit-interval="10"/>

</tasklet>

</step>

</job>The following Java example shows how to configure a job to have steps that can be restarted:

@Bean

public Job footballJob() {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("footballJob")

.start(playerLoad())

.next(gameLoad())

.next(playerSummarization())

.build();

}

@Bean

public Step playerLoad() {

return this.stepBuilderFactory.get("playerLoad")

.<String, String>chunk(10)

.reader(playerFileItemReader())

.writer(playerWriter())

.build();

}

@Bean

public Step gameLoad() {

return this.stepBuilderFactory.get("gameLoad")

.allowStartIfComplete(true)

.<String, String>chunk(10)

.reader(gameFileItemReader())

.writer(gameWriter())

.build();

}

@Bean

public Step playerSummarization() {

return this.stepBuilderFactory.get("playerSummarization")

.startLimit(2)

.<String, String>chunk(10)

.reader(playerSummarizationSource())

.writer(summaryWriter())

.build();

}

The preceding example configuration is for a job that loads in information about football

games and summarizes them. It contains three steps: playerLoad, gameLoad, and

playerSummarization. The playerLoad step loads player information from a flat file,

while the gameLoad step does the same for games. The final step,

playerSummarization, then summarizes the statistics for each player, based upon the

provided games. It is assumed that the file loaded by playerLoad must be loaded only

once but that gameLoad can load any games found within a particular directory,

deleting them after they have been successfully loaded into the database. As a result,

the playerLoad step contains no additional configuration. It can be started any number

of times is skipped if complete. The gameLoad step, however, needs to be run

every time in case extra files have been added since it last ran. It has

allow-start-if-complete set to true to always be started. (It is assumed

that the database table that games are loaded into has a process indicator on it, to ensure

new games can be properly found by the summarization step). The summarization step,

which is the most important in the job, is configured to have a start limit of 2. This

is useful because, if the step continually fails, a new exit code is returned to the

operators that control job execution, and it can not start again until manual

intervention has taken place.

This job provides an example for this document and is not the same as the footballJob

found in the samples project.

|

The remainder of this section describes what happens for each of the three runs of the

footballJob example.

Run 1:

-

playerLoadruns and completes successfully, adding 400 players to thePLAYERStable. -

gameLoadruns and processes 11 files worth of game data, loading their contents into theGAMEStable. -

playerSummarizationbegins processing and fails after 5 minutes.

Run 2:

-

playerLoaddoes not run, since it has already completed successfully, andallow-start-if-completeisfalse(the default). -

gameLoadruns again and processes another 2 files, loading their contents into theGAMEStable as well (with a process indicator indicating they have yet to be processed). -

playerSummarizationbegins processing of all remaining game data (filtering using the process indicator) and fails again after 30 minutes.

Run 3:

-

playerLoaddoes not run, since it has already completed successfully, andallow-start-if-completeisfalse(the default). -

gameLoadruns again and processes another 2 files, loading their contents into theGAMEStable as well (with a process indicator indicating they have yet to be processed). -

playerSummarizationis not started and the job is immediately killed, since this is the third execution ofplayerSummarization, and its limit is only 2. Either the limit must be raised or theJobmust be executed as a newJobInstance.

Configuring Skip Logic

There are many scenarios where errors encountered while processing should not result in

Step failure but should be skipped instead. This is usually a decision that must be

made by someone who understands the data itself and what meaning it has. Financial data,

for example, may not be skippable because it results in money being transferred, which

needs to be completely accurate. Loading a list of vendors, on the other hand, might

allow for skips. If a vendor is not loaded because it was formatted incorrectly or was

missing necessary information, there probably are not issues. Usually, these bad

records are logged as well, which is covered later when discussing listeners.

The following XML example shows an example of using a skip limit:

<step id="step1">

<tasklet>

<chunk reader="flatFileItemReader" writer="itemWriter"

commit-interval="10" skip-limit="10">

<skippable-exception-classes>

<include class="org.springframework.batch.item.file.FlatFileParseException"/>

</skippable-exception-classes>

</chunk>

</tasklet>

</step>The following Java example shows an example of using a skip limit:

@Bean

public Step step1() {

return this.stepBuilderFactory.get("step1")

.<String, String>chunk(10)

.reader(flatFileItemReader())

.writer(itemWriter())

.faultTolerant()

.skipLimit(10)

.skip(FlatFileParseException.class)

.build();

}

In the preceding example, a FlatFileItemReader is used. If, at any point, a

FlatFileParseException is thrown, the item is skipped and counted against the total

skip limit of 10. Exceptions (and their subclasses) that are declared might be thrown

during any phase of the chunk processing (read, process, or write). Separate counts

are made of skips on read, process, and write inside

the step execution, but the limit applies across all skips. Once the skip limit is

reached, the next exception found causes the step to fail. In other words, the eleventh

skip triggers the exception, not the tenth.

One problem with the preceding example is that any other exception besides a

FlatFileParseException causes the Job to fail. In certain scenarios, this may be the

correct behavior. However, in other scenarios, it may be easier to identify which

exceptions should cause failure and skip everything else.

The following XML example shows an example excluding a particular exception:

<step id="step1">

<tasklet>

<chunk reader="flatFileItemReader" writer="itemWriter"

commit-interval="10" skip-limit="10">

<skippable-exception-classes>

<include class="java.lang.Exception"/>

<exclude class="java.io.FileNotFoundException"/>

</skippable-exception-classes>

</chunk>

</tasklet>

</step>The following Java example shows an example excluding a particular exception:

@Bean

public Step step1() {

return this.stepBuilderFactory.get("step1")

.<String, String>chunk(10)

.reader(flatFileItemReader())

.writer(itemWriter())

.faultTolerant()

.skipLimit(10)

.skip(Exception.class)

.noSkip(FileNotFoundException.class)

.build();

}

By identifying java.lang.Exception as a skippable exception class, the configuration

indicates that all Exceptions are skippable. However, by “excluding”

java.io.FileNotFoundException, the configuration refines the list of skippable

exception classes to be all Exceptions except FileNotFoundException. Any excluded

exception class is fatal if encountered (that is, they are not skipped).

For any exception encountered, the skippability is determined by the nearest superclass in the class hierarchy. Any unclassified exception is treated as 'fatal'.

Configuring Retry Logic

In most cases, you want an exception to cause either a skip or a Step failure. However,

not all exceptions are deterministic. If a FlatFileParseException is encountered while

reading, it is always thrown for that record. Resetting the ItemReader does not help.

However, for other exceptions (such as a DeadlockLoserDataAccessException, which

indicates that the current process has attempted to update a record that another process

holds a lock on), waiting and trying again might result in success.

In XML, retry should be configured as follows:

<step id="step1">

<tasklet>

<chunk reader="itemReader" writer="itemWriter"

commit-interval="2" retry-limit="3">

<retryable-exception-classes>

<include class="org.springframework.dao.DeadlockLoserDataAccessException"/>

</retryable-exception-classes>

</chunk>

</tasklet>

</step>In Java, retry should be configured as follows:

@Bean

public Step step1() {

return this.stepBuilderFactory.get("step1")

.<String, String>chunk(2)

.reader(itemReader())

.writer(itemWriter())

.faultTolerant()

.retryLimit(3)

.retry(DeadlockLoserDataAccessException.class)

.build();

}

The Step allows a limit for the number of times an individual item can be retried and a

list of exceptions that are “retryable”. You can find more details on how retry works in

retry.

Controlling Rollback

By default, regardless of retry or skip, any exceptions thrown from the ItemWriter

cause the transaction controlled by the Step to rollback. If skip is configured as

described earlier, exceptions thrown from the ItemReader do not cause a rollback.

However, there are many scenarios in which exceptions thrown from the ItemWriter should

not cause a rollback, because no action has taken place to invalidate the transaction.

For this reason, you can configure the Step with a list of exceptions that should not

cause rollback.

In XML, you can control rollback as follows:

<step id="step1">

<tasklet>

<chunk reader="itemReader" writer="itemWriter" commit-interval="2"/>

<no-rollback-exception-classes>

<include class="org.springframework.batch.item.validator.ValidationException"/>

</no-rollback-exception-classes>

</tasklet>

</step>In Java, you can control rollback as follows:

@Bean

public Step step1() {

return this.stepBuilderFactory.get("step1")

.<String, String>chunk(2)

.reader(itemReader())

.writer(itemWriter())

.faultTolerant()

.noRollback(ValidationException.class)

.build();

}

Transactional Readers

The basic contract of the ItemReader is that it is forward-only. The step buffers

reader input so that, in case of a rollback, the items do not need to be re-read

from the reader. However, there are certain scenarios in which the reader is built on

top of a transactional resource, such as a JMS queue. In this case, since the queue is

tied to the transaction that is rolled back, the messages that have been pulled from the

queue are put back on. For this reason, you can configure the step to not buffer the

items.

The following example shows how to create a reader that does not buffer items in XML:

<step id="step1">

<tasklet>

<chunk reader="itemReader" writer="itemWriter" commit-interval="2"

is-reader-transactional-queue="true"/>

</tasklet>

</step>The following example shows how to create a reader that does not buffer items in Java:

@Bean

public Step step1() {

return this.stepBuilderFactory.get("step1")

.<String, String>chunk(2)

.reader(itemReader())

.writer(itemWriter())

.readerIsTransactionalQueue()

.build();

}

Transaction Attributes

You can use transaction attributes to control the isolation, propagation, and

timeout settings. You can find more information on setting transaction attributes in

the

Spring

core documentation.

The following example sets the isolation, propagation, and timeout transaction

attributes in XML:

<step id="step1">

<tasklet>

<chunk reader="itemReader" writer="itemWriter" commit-interval="2"/>

<transaction-attributes isolation="DEFAULT"

propagation="REQUIRED"

timeout="30"/>

</tasklet>

</step>The following example sets the isolation, propagation, and timeout transaction

attributes in Java:

@Bean

public Step step1() {

DefaultTransactionAttribute attribute = new DefaultTransactionAttribute();

attribute.setPropagationBehavior(Propagation.REQUIRED.value());

attribute.setIsolationLevel(Isolation.DEFAULT.value());

attribute.setTimeout(30);

return this.stepBuilderFactory.get("step1")

.<String, String>chunk(2)

.reader(itemReader())

.writer(itemWriter())

.transactionAttribute(attribute)

.build();

}

Registering ItemStream with a Step

The step has to take care of ItemStream callbacks at the necessary points in its

lifecycle. (For more information on the ItemStream interface, see

ItemStream). This is vital if a step fails and might

need to be restarted, because the ItemStream interface is where the step gets the

information it needs about persistent state between executions.

If the ItemReader, ItemProcessor, or ItemWriter itself implements the ItemStream

interface, these are registered automatically. Any other streams need to be

registered separately. This is often the case where indirect dependencies, such as

delegates, are injected into the reader and writer. You can register a stream on the

step through the stream element.

The following example shows how to register a stream on a step in XML:

<step id="step1">

<tasklet>

<chunk reader="itemReader" writer="compositeWriter" commit-interval="2">

<streams>

<stream ref="fileItemWriter1"/>

<stream ref="fileItemWriter2"/>

</streams>

</chunk>

</tasklet>

</step>

<beans:bean id="compositeWriter"

class="org.springframework.batch.item.support.CompositeItemWriter">

<beans:property name="delegates">

<beans:list>

<beans:ref bean="fileItemWriter1" />

<beans:ref bean="fileItemWriter2" />

</beans:list>

</beans:property>

</beans:bean>The following example shows how to register a stream on a step in Java:

@Bean

public Step step1() {

return this.stepBuilderFactory.get("step1")

.<String, String>chunk(2)

.reader(itemReader())

.writer(compositeItemWriter())

.stream(fileItemWriter1())

.stream(fileItemWriter2())

.build();

}

/**

* In Spring Batch 4, the CompositeItemWriter implements ItemStream so this isn't

* necessary, but used for an example.

*/

@Bean

public CompositeItemWriter compositeItemWriter() {

List<ItemWriter> writers = new ArrayList<>(2);

writers.add(fileItemWriter1());

writers.add(fileItemWriter2());

CompositeItemWriter itemWriter = new CompositeItemWriter();

itemWriter.setDelegates(writers);

return itemWriter;

}

In the preceding example, the CompositeItemWriter is not an ItemStream, but both of its

delegates are. Therefore, both delegate writers must be explicitly registered as streams

for the framework to handle them correctly. The ItemReader does not need to be

explicitly registered as a stream because it is a direct property of the Step. The step

is now restartable, and the state of the reader and writer is correctly persisted in the

event of a failure.

Intercepting Step Execution

Just as with the Job, there are many events during the execution of a Step where a

user may need to perform some functionality. For example, to write out to a flat

file that requires a footer, the ItemWriter needs to be notified when the Step has

been completed so that the footer can be written. This can be accomplished with one of many

Step scoped listeners.

You can apply any class that implements one of the extensions of StepListener (but not that interface

itself, since it is empty) to a step through the listeners element.

The listeners element is valid inside a step, tasklet, or chunk declaration. We

recommend that you declare the listeners at the level at which its function applies

or, if it is multi-featured (such as StepExecutionListener and ItemReadListener),

declare it at the most granular level where it applies.

The following example shows a listener applied at the chunk level in XML:

<step id="step1">

<tasklet>

<chunk reader="reader" writer="writer" commit-interval="10"/>

<listeners>

<listener ref="chunkListener"/>

</listeners>

</tasklet>

</step>The following example shows a listener applied at the chunk level in Java:

@Bean

public Step step1() {

return this.stepBuilderFactory.get("step1")

.<String, String>chunk(10)

.reader(reader())

.writer(writer())

.listener(chunkListener())

.build();

}

An ItemReader, ItemWriter, or ItemProcessor that itself implements one of the

StepListener interfaces is registered automatically with the Step if using the

namespace <step> element or one of the *StepFactoryBean factories. This only

applies to components directly injected into the Step. If the listener is nested inside

another component, you need to explicitly register it (as described previously under

Registering ItemStream with a Step).

In addition to the StepListener interfaces, annotations are provided to address the

same concerns. Plain old Java objects can have methods with these annotations that are

then converted into the corresponding StepListener type. It is also common to annotate

custom implementations of chunk components, such as ItemReader or ItemWriter or

Tasklet. The annotations are analyzed by the XML parser for the <listener/> elements

as well as registered with the listener methods in the builders, so all you need to do

is use the XML namespace or builders to register the listeners with a step.

StepExecutionListener

StepExecutionListener represents the most generic listener for Step execution. It

allows for notification before a Step is started and after it ends, whether it ended

normally or failed, as the following example shows:

public interface StepExecutionListener extends StepListener {

void beforeStep(StepExecution stepExecution);

ExitStatus afterStep(StepExecution stepExecution);

}

ExitStatus has a return type of afterStep, to give listeners the chance to

modify the exit code that is returned upon completion of a Step.

The annotations corresponding to this interface are:

-

@BeforeStep -

@AfterStep

ChunkListener

A “chunk” is defined as the items processed within the scope of a transaction. Committing a

transaction, at each commit interval, commits a chunk. You can use a ChunkListener to

perform logic before a chunk begins processing or after a chunk has completed

successfully, as the following interface definition shows:

public interface ChunkListener extends StepListener {

void beforeChunk(ChunkContext context);

void afterChunk(ChunkContext context);

void afterChunkError(ChunkContext context);

}

The beforeChunk method is called after the transaction is started but before reading begins

on the ItemReader. Conversely, afterChunk is called after the chunk has been

committed (or not at all if there is a rollback).

The annotations corresponding to this interface are:

-

@BeforeChunk -

@AfterChunk -

@AfterChunkError

You can apply a ChunkListener when there is no chunk declaration. The TaskletStep is

responsible for calling the ChunkListener, so it applies to a non-item-oriented tasklet

as well (it is called before and after the tasklet).

ItemReadListener

When discussing skip logic previously, it was mentioned that it may be beneficial to log

the skipped records so that they can be dealt with later. In the case of read errors,

this can be done with an ItemReaderListener, as the following interface

definition shows:

public interface ItemReadListener<T> extends StepListener {

void beforeRead();

void afterRead(T item);

void onReadError(Exception ex);

}

The beforeRead method is called before each call to read on the ItemReader. The

afterRead method is called after each successful call to read and is passed the item

that was read. If there was an error while reading, the onReadError method is called.

The exception encountered is provided so that it can be logged.

The annotations corresponding to this interface are:

-

@BeforeRead -

@AfterRead -

@OnReadError

ItemProcessListener

As with the ItemReadListener, the processing of an item can be “listened” to, as

the following interface definition shows:

public interface ItemProcessListener<T, S> extends StepListener {

void beforeProcess(T item);

void afterProcess(T item, S result);

void onProcessError(T item, Exception e);

}

The beforeProcess method is called before process on the ItemProcessor and is

handed the item that is to be processed. The afterProcess method is called after the

item has been successfully processed. If there was an error while processing, the

onProcessError method is called. The exception encountered and the item that was

attempted to be processed are provided, so that they can be logged.

The annotations corresponding to this interface are:

-

@BeforeProcess -

@AfterProcess -

@OnProcessError

ItemWriteListener

You can “listen” to the writing of an item with the ItemWriteListener, as the

following interface definition shows:

public interface ItemWriteListener<S> extends StepListener {

void beforeWrite(List<? extends S> items);

void afterWrite(List<? extends S> items);

void onWriteError(Exception exception, List<? extends S> items);

}

The beforeWrite method is called before write on the ItemWriter and is handed the

list of items that is written. The afterWrite method is called after the item has been

successfully written. If there was an error while writing, the onWriteError method is

called. The exception encountered and the item that was attempted to be written are

provided, so that they can be logged.

The annotations corresponding to this interface are:

-

@BeforeWrite -

@AfterWrite -

@OnWriteError

SkipListener

ItemReadListener, ItemProcessListener, and ItemWriteListener all provide mechanisms

for being notified of errors, but none informs you that a record has actually been

skipped. onWriteError, for example, is called even if an item is retried and

successful. For this reason, there is a separate interface for tracking skipped items, as

the following interface definition shows:

public interface SkipListener<T,S> extends StepListener {

void onSkipInRead(Throwable t);

void onSkipInProcess(T item, Throwable t);

void onSkipInWrite(S item, Throwable t);

}

onSkipInRead is called whenever an item is skipped while reading. It should be noted

that rollbacks may cause the same item to be registered as skipped more than once.

onSkipInWrite is called when an item is skipped while writing. Because the item has

been read successfully (and not skipped), it is also provided the item itself as an

argument.

The annotations corresponding to this interface are:

-

@OnSkipInRead -

@OnSkipInWrite -

@OnSkipInProcess

SkipListeners and Transactions

One of the most common use cases for a SkipListener is to log out a skipped item, so

that another batch process or even human process can be used to evaluate and fix the

issue that leads to the skip. Because there are many cases in which the original transaction

may be rolled back, Spring Batch makes two guarantees:

-

The appropriate skip method (depending on when the error happened) is called only once per item.

-

The

SkipListeneris always called just before the transaction is committed. This is to ensure that any transactional resources call by the listener are not rolled back by a failure within theItemWriter.

TaskletStep

Chunk-oriented processing is not the only way to process in a

Step. What if a Step must consist of a stored procedure call? You could

implement the call as an ItemReader and return null after the procedure finishes.

However, doing so is a bit unnatural, since there would need to be a no-op ItemWriter.

Spring Batch provides the TaskletStep for this scenario.

The Tasklet interface has one method, execute, which is called

repeatedly by the TaskletStep until it either returns RepeatStatus.FINISHED or throws

an exception to signal a failure. Each call to a Tasklet is wrapped in a transaction.

Tasklet implementors might call a stored procedure, a script, or a SQL update

statement.

If it implements the StepListener interface, TaskletStep automatically registers the tasklet as a StepListener.

|

TaskletAdapter

As with other adapters for the ItemReader and ItemWriter interfaces, the Tasklet

interface contains an implementation that allows for adapting itself to any pre-existing

class: TaskletAdapter. An example where this may be useful is an existing DAO that is

used to update a flag on a set of records. You can use the TaskletAdapter to call this

class without having to write an adapter for the Tasklet interface.

The following example shows how to define a TaskletAdapter in XML:

<bean id="myTasklet" class="o.s.b.core.step.tasklet.MethodInvokingTaskletAdapter">

<property name="targetObject">

<bean class="org.mycompany.FooDao"/>

</property>

<property name="targetMethod" value="updateFoo" />

</bean>The following example shows how to define a TaskletAdapter in Java:

@Bean

public MethodInvokingTaskletAdapter myTasklet() {

MethodInvokingTaskletAdapter adapter = new MethodInvokingTaskletAdapter();

adapter.setTargetObject(fooDao());

adapter.setTargetMethod("updateFoo");

return adapter;

}

Example Tasklet Implementation

Many batch jobs contain steps that must be done before the main processing begins,

to set up various resources or after processing has completed to cleanup those

resources. In the case of a job that works heavily with files, it is often necessary to

delete certain files locally after they have been uploaded successfully to another

location. The following example (taken from the

Spring

Batch samples project) is a Tasklet implementation with just such a responsibility:

public class FileDeletingTasklet implements Tasklet, InitializingBean {

private Resource directory;

public RepeatStatus execute(StepContribution contribution,

ChunkContext chunkContext) throws Exception {

File dir = directory.getFile();

Assert.state(dir.isDirectory());

File[] files = dir.listFiles();

for (int i = 0; i < files.length; i++) {

boolean deleted = files[i].delete();

if (!deleted) {

throw new UnexpectedJobExecutionException("Could not delete file " +

files[i].getPath());

}

}

return RepeatStatus.FINISHED;

}

public void setDirectoryResource(Resource directory) {

this.directory = directory;

}

public void afterPropertiesSet() throws Exception {

Assert.notNull(directory, "directory must be set");

}

}

The preceding tasklet implementation deletes all files within a given directory. It

should be noted that the execute method is called only once. All that is left is to

reference the tasklet from the step.

The following example shows how to reference the tasklet from the step in XML:

<job id="taskletJob">

<step id="deleteFilesInDir">

<tasklet ref="fileDeletingTasklet"/>

</step>

</job>

<beans:bean id="fileDeletingTasklet"

class="org.springframework.batch.sample.tasklet.FileDeletingTasklet">

<beans:property name="directoryResource">

<beans:bean id="directory"

class="org.springframework.core.io.FileSystemResource">

<beans:constructor-arg value="target/test-outputs/test-dir" />

</beans:bean>

</beans:property>

</beans:bean>The following example shows how to reference the tasklet from the step in Java:

@Bean

public Job taskletJob() {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("taskletJob")

.start(deleteFilesInDir())

.build();

}

@Bean

public Step deleteFilesInDir() {

return this.stepBuilderFactory.get("deleteFilesInDir")

.tasklet(fileDeletingTasklet())

.build();

}

@Bean

public FileDeletingTasklet fileDeletingTasklet() {

FileDeletingTasklet tasklet = new FileDeletingTasklet();

tasklet.setDirectoryResource(new FileSystemResource("target/test-outputs/test-dir"));

return tasklet;

}

Controlling Step Flow

With the ability to group steps together within an owning job comes the need to be able

to control how the job “flows” from one step to another. The failure of a Step does not

necessarily mean that the Job should fail. Furthermore, there may be more than one type

of “success” that determines which Step should be executed next. Depending upon how a

group of Steps is configured, certain steps may not even be processed at all.

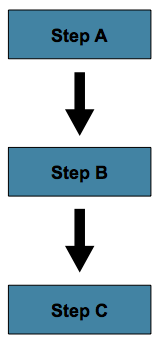

Sequential Flow

The simplest flow scenario is a job where all of the steps execute sequentially, as the following image shows:

This can be achieved by using next in a step.

The following example shows how to use the next attribute in XML:

<job id="job">

<step id="stepA" parent="s1" next="stepB" />

<step id="stepB" parent="s2" next="stepC"/>

<step id="stepC" parent="s3" />

</job>The following example shows how to use the next() method in Java:

@Bean

public Job job() {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("job")

.start(stepA())

.next(stepB())

.next(stepC())

.build();

}

In the scenario above, stepA runs first because it is the first Step listed. If

stepA completes normally, stepB runs, and so on. However, if step A fails,

the entire Job fails and stepB does not execute.

With the Spring Batch XML namespace, the first step listed in the configuration is

always the first step run by the Job. The order of the other step elements does not

matter, but the first step must always appear first in the XML.

|

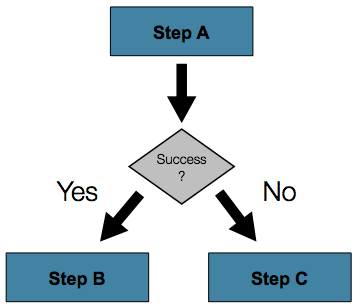

Conditional Flow

In the preceding example, there are only two possibilities:

-

The

stepis successful, and the nextstepshould be executed. -

The

stepfailed, and, thus, thejobshould fail.

In many cases, this may be sufficient. However, what about a scenario in which the

failure of a step should trigger a different step, rather than causing failure? The

following image shows such a flow:

To handle more complex scenarios, the Spring Batch XML namespace lets you define transitions

elements within the step element. One such transition is the next

element. Like the next attribute, the next element tells the Job which Step to

execute next. However, unlike the attribute, any number of next elements are allowed on

a given Step, and there is no default behavior in the case of failure. This means that, if

transition elements are used, all of the behavior for the Step transitions must be

defined explicitly. Note also that a single step cannot have both a next attribute and

a transition element.

The next element specifies a pattern to match and the step to execute next, as

the following example shows:

<job id="job">

<step id="stepA" parent="s1">

<next on="*" to="stepB" />

<next on="FAILED" to="stepC" />

</step>

<step id="stepB" parent="s2" next="stepC" />

<step id="stepC" parent="s3" />

</job>The Java API offers a fluent set of methods that let you specify the flow and what to do

when a step fails. The following example shows how to specify one step (stepA) and then

proceed to either of two different steps (stepB or stepC), depending on whether

stepA succeeds:

@Bean

public Job job() {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("job")

.start(stepA())

.on("*").to(stepB())

.from(stepA()).on("FAILED").to(stepC())

.end()

.build();

}

When using XML configuration, the on attribute of a transition element uses a simple

pattern-matching scheme to match the ExitStatus that results from the execution of the

Step.

When using java configuration, the on() method uses a simple pattern-matching scheme to

match the ExitStatus that results from the execution of the Step.

Only two special characters are allowed in the pattern:

-

*matches zero or more characters -

?matches exactly one character

For example, c*t matches cat and count, while c?t matches cat but not count.

While there is no limit to the number of transition elements on a Step, if the Step

execution results in an ExitStatus that is not covered by an element, the

framework throws an exception and the Job fails. The framework automatically orders

transitions from most specific to least specific. This means that, even if the ordering

were swapped for stepA in the preceding example, an ExitStatus of FAILED would still go

to stepC.

Batch Status Versus Exit Status

When configuring a Job for conditional flow, it is important to understand the

difference between BatchStatus and ExitStatus. BatchStatus is an enumeration that

is a property of both JobExecution and StepExecution and is used by the framework to

record the status of a Job or Step. It can be one of the following values:

COMPLETED, STARTING, STARTED, STOPPING, STOPPED, FAILED, ABANDONED, or

UNKNOWN. Most of them are self explanatory: COMPLETED is the status set when a step

or job has completed successfully, FAILED is set when it fails, and so on.

The following example contains the next element when using XML configuration:

<next on="FAILED" to="stepB" />The following example contains the on element when using Java Configuration:

...

.from(stepA()).on("FAILED").to(stepB())

...

At first glance, it would appear that on references the BatchStatus of the Step to

which it belongs. However, it actually references the ExitStatus of the Step. As the

name implies, ExitStatus represents the status of a Step after it finishes execution.

More specifically, when using XML configuration, the next element shown in the

preceding XML configuration example references the exit code of ExitStatus.

When using Java configuration, the on() method shown in the preceding

Java configuration example references the exit code of ExitStatus.

In English, it says: “go to stepB if the exit code is FAILED”. By default, the exit

code is always the same as the BatchStatus for the Step, which is why the preceding entry

works. However, what if the exit code needs to be different? A good example comes from

the skip sample job within the samples project:

The following example shows how to work with a different exit code in XML:

<step id="step1" parent="s1">

<end on="FAILED" />

<next on="COMPLETED WITH SKIPS" to="errorPrint1" />

<next on="*" to="step2" />

</step>The following example shows how to work with a different exit code in Java:

@Bean

public Job job() {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("job")

.start(step1()).on("FAILED").end()

.from(step1()).on("COMPLETED WITH SKIPS").to(errorPrint1())

.from(step1()).on("*").to(step2())

.end()

.build();

}

step1 has three possibilities:

-

The

Stepfailed, in which case the job should fail. -

The

Stepcompleted successfully. -

The

Stepcompleted successfully but with an exit code ofCOMPLETED WITH SKIPS. In this case, a different step should be run to handle the errors.

The preceding configuration works. However, something needs to change the exit code based on the condition of the execution having skipped records, as the following example shows:

public class SkipCheckingListener extends StepExecutionListenerSupport {

public ExitStatus afterStep(StepExecution stepExecution) {

String exitCode = stepExecution.getExitStatus().getExitCode();

if (!exitCode.equals(ExitStatus.FAILED.getExitCode()) &&

stepExecution.getSkipCount() > 0) {

return new ExitStatus("COMPLETED WITH SKIPS");

}

else {

return null;

}

}

}

The preceding code is a StepExecutionListener that first checks to make sure the Step was

successful and then checks to see if the skip count on the StepExecution is higher than

0. If both conditions are met, a new ExitStatus with an exit code of

COMPLETED WITH SKIPS is returned.

Configuring for Stop

After the discussion of BatchStatus and ExitStatus,

one might wonder how the BatchStatus and ExitStatus are determined for the Job.

While these statuses are determined for the Step by the code that is executed, the

statuses for the Job are determined based on the configuration.

So far, all of the job configurations discussed have had at least one final Step with

no transitions.

In the following XML example, after the step executes, the Job ends:

<step id="stepC" parent="s3"/>In the following Java example, after the step executes, the Job ends:

@Bean

public Job job() {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("job")

.start(step1())

.build();

}

If no transitions are defined for a Step, the status of the Job is defined as

follows:

-

If the

Stepends withExitStatusofFAILED, theBatchStatusandExitStatusof theJobare bothFAILED. -

Otherwise, the

BatchStatusandExitStatusof theJobare bothCOMPLETED.

While this method of terminating a batch job is sufficient for some batch jobs, such as a

simple sequential step job, custom defined job-stopping scenarios may be required. For

this purpose, Spring Batch provides three transition elements to stop a Job (in

addition to the next element that we discussed previously).

Each of these stopping elements stops a Job with a particular BatchStatus. It is

important to note that the stop transition elements have no effect on either the

BatchStatus or ExitStatus of any Steps in the Job. These elements affect only the

final statuses of the Job. For example, it is possible for every step in a job to have

a status of FAILED but for the job to have a status of COMPLETED.

Ending at a Step

Configuring a step end instructs a Job to stop with a BatchStatus of COMPLETED. A

Job that has finished with a status of COMPLETED cannot be restarted (the framework throws

a JobInstanceAlreadyCompleteException).

When using XML configuration, you can use the end element for this task. The end element

also allows for an optional exit-code attribute that you can use to customize the

ExitStatus of the Job. If no exit-code attribute is given, the ExitStatus is

COMPLETED by default, to match the BatchStatus.

When using Java configuration, the end method is used for this task. The end method

also allows for an optional exitStatus parameter that you can use to customize the

ExitStatus of the Job. If no exitStatus value is provided, the ExitStatus is

COMPLETED by default, to match the BatchStatus.

Consider the following scenario: If step2 fails, the Job stops with a

BatchStatus of COMPLETED and an ExitStatus of COMPLETED, and step3 does not run.

Otherwise, execution moves to step3. Note that if step2 fails, the Job is not

restartable (because the status is COMPLETED).

The following example shows the scenario in XML:

<step id="step1" parent="s1" next="step2">

<step id="step2" parent="s2">

<end on="FAILED"/>

<next on="*" to="step3"/>

</step>

<step id="step3" parent="s3">The following example shows the scenario in Java:

@Bean

public Job job() {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("job")

.start(step1())

.next(step2())

.on("FAILED").end()

.from(step2()).on("*").to(step3())

.end()

.build();

}

Failing a Step

Configuring a step to fail at a given point instructs a Job to stop with a

BatchStatus of FAILED. Unlike end, the failure of a Job does not prevent the Job

from being restarted.

When using XML configuration, the fail element also allows for an optional exit-code

attribute that can be used to customize the ExitStatus of the Job. If no exit-code

attribute is given, the ExitStatus is FAILED by default, to match the

BatchStatus.

Consider the following scenario: If step2 fails, the Job stops with a

BatchStatus of FAILED and an ExitStatus of EARLY TERMINATION and step3 does not

execute. Otherwise, execution moves to step3. Additionally, if step2 fails and the

Job is restarted, execution begins again on step2.

The following example shows the scenario in XML:

<step id="step1" parent="s1" next="step2">

<step id="step2" parent="s2">

<fail on="FAILED" exit-code="EARLY TERMINATION"/>

<next on="*" to="step3"/>

</step>

<step id="step3" parent="s3">The following example shows the scenario in Java:

@Bean

public Job job() {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("job")

.start(step1())

.next(step2()).on("FAILED").fail()

.from(step2()).on("*").to(step3())

.end()

.build();

}

Stopping a Job at a Given Step

Configuring a job to stop at a particular step instructs a Job to stop with a

BatchStatus of STOPPED. Stopping a Job can provide a temporary break in processing,

so that the operator can take some action before restarting the Job.

When using XML configuration, a stop element requires a restart attribute that specifies

the step where execution should pick up when the Job is restarted.

When using Java configuration, the stopAndRestart method requires a restart attribute

that specifies the step where execution should pick up when the Job is restarted.

Consider the following scenario: If step1 finishes with COMPLETE, the job then

stops. Once it is restarted, execution begins on step2.

The following listing shows the scenario in XML:

<step id="step1" parent="s1">

<stop on="COMPLETED" restart="step2"/>

</step>

<step id="step2" parent="s2"/>The following example shows the scenario in Java:

@Bean

public Job job() {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("job")

.start(step1()).on("COMPLETED").stopAndRestart(step2())

.end()

.build();

}

Programmatic Flow Decisions

In some situations, more information than the ExitStatus may be required to decide

which step to execute next. In this case, a JobExecutionDecider can be used to assist

in the decision, as the following example shows:

public class MyDecider implements JobExecutionDecider {

public FlowExecutionStatus decide(JobExecution jobExecution, StepExecution stepExecution) {

String status;

if (someCondition()) {

status = "FAILED";

}

else {

status = "COMPLETED";

}

return new FlowExecutionStatus(status);

}

}

In the following sample job configuration, a decision specifies the decider to use as

well as all of the transitions:

<job id="job">

<step id="step1" parent="s1" next="decision" />

<decision id="decision" decider="decider">

<next on="FAILED" to="step2" />

<next on="COMPLETED" to="step3" />

</decision>

<step id="step2" parent="s2" next="step3"/>

<step id="step3" parent="s3" />

</job>

<beans:bean id="decider" class="com.MyDecider"/>In the following example, a bean implementing the JobExecutionDecider is passed

directly to the next call when using Java configuration:

@Bean

public Job job() {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("job")

.start(step1())

.next(decider()).on("FAILED").to(step2())

.from(decider()).on("COMPLETED").to(step3())

.end()

.build();

}

Split Flows

Every scenario described so far has involved a Job that executes its steps one at a

time in a linear fashion. In addition to this typical style, Spring Batch also allows

for a job to be configured with parallel flows.

The XML namespace lets you use the split element. As the following example shows,

the split element contains one or more flow elements, where entire separate flows can

be defined. A split element can also contain any of the previously discussed transition

elements, such as the next attribute or the next, end, or fail elements.

<split id="split1" next="step4">

<flow>

<step id="step1" parent="s1" next="step2"/>

<step id="step2" parent="s2"/>

</flow>

<flow>

<step id="step3" parent="s3"/>

</flow>

</split>

<step id="step4" parent="s4"/>Java-based configuration lets you configure splits through the provided builders. As the

following example shows, the split element contains one or more flow elements, where

entire separate flows can be defined. A split element can also contain any of the

previously discussed transition elements, such as the next attribute or the next,

end, or fail elements.

@Bean

public Flow flow1() {

return new FlowBuilder<SimpleFlow>("flow1")

.start(step1())

.next(step2())

.build();

}

@Bean

public Flow flow2() {

return new FlowBuilder<SimpleFlow>("flow2")

.start(step3())

.build();

}

@Bean

public Job job(Flow flow1, Flow flow2) {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("job")

.start(flow1)

.split(new SimpleAsyncTaskExecutor())

.add(flow2)

.next(step4())

.end()

.build();

}

Externalizing Flow Definitions and Dependencies Between Jobs

Part of the flow in a job can be externalized as a separate bean definition and then re-used. There are two ways to do so. The first is to declare the flow as a reference to one defined elsewhere.

The following XML example shows how to declare a flow as a reference to a flow defined elsewhere:

<job id="job">

<flow id="job1.flow1" parent="flow1" next="step3"/>

<step id="step3" parent="s3"/>

</job>

<flow id="flow1">

<step id="step1" parent="s1" next="step2"/>

<step id="step2" parent="s2"/>

</flow>The following Java example shows how to declare a flow as a reference to a flow defined elsewhere:

@Bean

public Job job() {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("job")

.start(flow1())

.next(step3())

.end()

.build();

}

@Bean

public Flow flow1() {

return new FlowBuilder<SimpleFlow>("flow1")

.start(step1())

.next(step2())

.build();

}

The effect of defining an external flow, as shown in the preceding example, is to insert the steps from the external flow into the job as if they had been declared inline. In this way, many jobs can refer to the same template flow and compose such templates into different logical flows. This is also a good way to separate the integration testing of the individual flows.

The other form of an externalized flow is to use a JobStep. A JobStep is similar to a

FlowStep but actually creates and launches a separate job execution for the steps in

the flow specified.

The following example hows an example of a JobStep in XML:

<job id="jobStepJob" restartable="true">

<step id="jobStepJob.step1">

<job ref="job" job-launcher="jobLauncher"

job-parameters-extractor="jobParametersExtractor"/>

</step>

</job>

<job id="job" restartable="true">...</job>

<bean id="jobParametersExtractor" class="org.spr...DefaultJobParametersExtractor">

<property name="keys" value="input.file"/>

</bean>The following example shows an example of a JobStep in Java:

@Bean

public Job jobStepJob() {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("jobStepJob")

.start(jobStepJobStep1(null))

.build();

}

@Bean

public Step jobStepJobStep1(JobLauncher jobLauncher) {

return this.stepBuilderFactory.get("jobStepJobStep1")

.job(job())

.launcher(jobLauncher)

.parametersExtractor(jobParametersExtractor())

.build();

}

@Bean

public Job job() {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("job")

.start(step1())

.build();

}

@Bean

public DefaultJobParametersExtractor jobParametersExtractor() {

DefaultJobParametersExtractor extractor = new DefaultJobParametersExtractor();

extractor.setKeys(new String[]{"input.file"});

return extractor;

}

The job parameters extractor is a strategy that determines how the ExecutionContext for

the Step is converted into JobParameters for the Job that is run. The JobStep is

useful when you want to have some more granular options for monitoring and reporting on

jobs and steps. Using JobStep is also often a good answer to the question: “How do I

create dependencies between jobs?” It is a good way to break up a large system into

smaller modules and control the flow of jobs.

Late Binding of Job and Step Attributes

Both the XML and flat file examples shown earlier use the Spring Resource abstraction

to obtain a file. This works because Resource has a getFile method that returns a

java.io.File. You can configure both XML and flat file resources by using standard Spring

constructs:

The following example shows late binding in XML:

<bean id="flatFileItemReader"

class="org.springframework.batch.item.file.FlatFileItemReader">

<property name="resource"

value="file://outputs/file.txt" />

</bean>The following example shows late binding in Java:

@Bean

public FlatFileItemReader flatFileItemReader() {

FlatFileItemReader<Foo> reader = new FlatFileItemReaderBuilder<Foo>()

.name("flatFileItemReader")

.resource(new FileSystemResource("file://outputs/file.txt"))

...

}

The preceding Resource loads the file from the specified file system location. Note

that absolute locations have to start with a double slash (//). In most Spring

applications, this solution is good enough, because the names of these resources are

known at compile time. However, in batch scenarios, the file name may need to be

determined at runtime as a parameter to the job. This can be solved using -D parameters

to read a system property.

The following example shows how to read a file name from a property in XML:

<bean id="flatFileItemReader"

class="org.springframework.batch.item.file.FlatFileItemReader">

<property name="resource" value="${input.file.name}" />

</bean>The following shows how to read a file name from a property in Java:

@Bean

public FlatFileItemReader flatFileItemReader(@Value("${input.file.name}") String name) {

return new FlatFileItemReaderBuilder<Foo>()

.name("flatFileItemReader")

.resource(new FileSystemResource(name))

...

}

All that would be required for this solution to work would be a system argument (such as

-Dinput.file.name="file://outputs/file.txt").

Although you can use a PropertyPlaceholderConfigurer here, it is not

necessary if the system property is always set because the ResourceEditor in Spring

already filters and does placeholder replacement on system properties.

|

Often, in a batch setting, it is preferable to parameterize the file name in the

JobParameters of the job (instead of through system properties) and access them that

way. To accomplish this, Spring Batch allows for the late binding of various Job and

Step attributes.

The following example shows how to parameterize a file name in XML:

<bean id="flatFileItemReader" scope="step"

class="org.springframework.batch.item.file.FlatFileItemReader">

<property name="resource" value="#{jobParameters['input.file.name']}" />

</bean>The following example shows how to parameterize a file name in Java:

@StepScope

@Bean

public FlatFileItemReader flatFileItemReader(@Value("#{jobParameters['input.file.name']}") String name) {

return new FlatFileItemReaderBuilder<Foo>()

.name("flatFileItemReader")

.resource(new FileSystemResource(name))

...

}

You can access both the JobExecution and StepExecution level ExecutionContext in

the same way.

The following example shows how to access the ExecutionContext in XML:

<bean id="flatFileItemReader" scope="step"

class="org.springframework.batch.item.file.FlatFileItemReader">

<property name="resource" value="#{jobExecutionContext['input.file.name']}" />

</bean><bean id="flatFileItemReader" scope="step"

class="org.springframework.batch.item.file.FlatFileItemReader">

<property name="resource" value="#{stepExecutionContext['input.file.name']}" />

</bean>The following example shows how to access the ExecutionContext in Java:

@StepScope

@Bean

public FlatFileItemReader flatFileItemReader(@Value("#{jobExecutionContext['input.file.name']}") String name) {

return new FlatFileItemReaderBuilder<Foo>()

.name("flatFileItemReader")

.resource(new FileSystemResource(name))

...

}

@StepScope

@Bean

public FlatFileItemReader flatFileItemReader(@Value("#{stepExecutionContext['input.file.name']}") String name) {

return new FlatFileItemReaderBuilder<Foo>()

.name("flatFileItemReader")

.resource(new FileSystemResource(name))

...

}

Any bean that uses late binding must be declared with scope="step". See

Step Scope for more information.

A Step bean should not be step-scoped. If late binding is needed in a step

definition, the components of that step (tasklet, item reader or writer, and so on)

are the ones that should be scoped instead.

|

| If you use Spring 3.0 (or above), the expressions in step-scoped beans are in the Spring Expression Language, a powerful general purpose language with many interesting features. To provide backward compatibility, if Spring Batch detects the presence of older versions of Spring, it uses a native expression language that is less powerful and that has slightly different parsing rules. The main difference is that the map keys in the example above do not need to be quoted with Spring 2.5, but the quotes are mandatory in Spring 3.0. |

Step Scope

All of the late binding examples shown earlier have a scope of step declared on the

bean definition.

The following example shows an example of binding to step scope in XML:

<bean id="flatFileItemReader" scope="step"

class="org.springframework.batch.item.file.FlatFileItemReader">

<property name="resource" value="#{jobParameters[input.file.name]}" />

</bean>The following example shows an example of binding to step scope in Java:

@StepScope

@Bean

public FlatFileItemReader flatFileItemReader(@Value("#{jobParameters[input.file.name]}") String name) {

return new FlatFileItemReaderBuilder<Foo>()

.name("flatFileItemReader")

.resource(new FileSystemResource(name))

...

}

Using a scope of Step is required to use late binding, because the bean cannot

actually be instantiated until the Step starts, to let the attributes be found.

Because it is not part of the Spring container by default, the scope must be added

explicitly, by using the batch namespace, by including a bean definition explicitly

for the StepScope, or by using the @EnableBatchProcessing annotation. Use only one of

those methods. The following example uses the batch namespace:

<beans xmlns="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans"

xmlns:batch="http://www.springframework.org/schema/batch"

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xsi:schemaLocation="...">

<batch:job .../>

...

</beans>The following example includes the bean definition explicitly:

<bean class="org.springframework.batch.core.scope.StepScope" />Job Scope

Job scope, introduced in Spring Batch 3.0, is similar to Step scope in configuration

but is a scope for the Job context, so that there is only one instance of such a bean

per running job. Additionally, support is provided for late binding of references

accessible from the JobContext by using #{..} placeholders. Using this feature, you can pull bean

properties from the job or job execution context and the job parameters.

The following example shows an example of binding to job scope in XML:

<bean id="..." class="..." scope="job">

<property name="name" value="#{jobParameters[input]}" />

</bean><bean id="..." class="..." scope="job">

<property name="name" value="#{jobExecutionContext['input.name']}.txt" />

</bean>The following example shows an example of binding to job scope in Java:

@JobScope

@Bean

public FlatFileItemReader flatFileItemReader(@Value("#{jobParameters[input]}") String name) {

return new FlatFileItemReaderBuilder<Foo>()

.name("flatFileItemReader")

.resource(new FileSystemResource(name))

...

}

@JobScope

@Bean

public FlatFileItemReader flatFileItemReader(@Value("#{jobExecutionContext['input.name']}") String name) {

return new FlatFileItemReaderBuilder<Foo>()

.name("flatFileItemReader")

.resource(new FileSystemResource(name))

...

}

Because it is not part of the Spring container by default, the scope must be added

explicitly, by using the batch namespace, by including a bean definition explicitly for

the JobScope, or by using the @EnableBatchProcessing annotation (choose only one approach).

The following example uses the batch namespace:

<beans xmlns="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans"

xmlns:batch="http://www.springframework.org/schema/batch"

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xsi:schemaLocation="...">

<batch:job .../>

...

</beans>The following example includes a bean that explicitly defines the JobScope:

<bean class="org.springframework.batch.core.scope.JobScope" />| There are some practical limitations of using job-scoped beans in multi-threaded or partitioned steps. Spring Batch does not control the threads spawned in these use cases, so it is not possible to set them up correctly to use such beans. Hence, we do not recommend using job-scoped beans in multi-threaded or partitioned steps. |