Spring Framework is a Java platform that provides comprehensive infrastructure support for developing Java applications. Spring handles the infrastructure so you can focus on your application.

Spring enables you to build applications from "plain old Java objects" (POJOs) and to apply enterprise services non-invasively to POJOs. This capability applies to the Java SE programming model and to full and partial Java EE.

Examples of how you, as an application developer, can use the Spring platform advantage:

- Make a Java method execute in a database transaction without having to deal with transaction APIs.

- Make a local Java method a remote procedure without having to deal with remote APIs.

- Make a local Java method a management operation without having to deal with JMX APIs.

- Make a local Java method a message handler without having to deal with JMS APIs.

Java applications — a loose term that runs the gamut from constrained applets to n-tier server-side enterprise applications — typically consist of objects that collaborate to form the application proper. Thus the objects in an application have dependencies on each other.

Although the Java platform provides a wealth of application development functionality, it lacks the means to organize the basic building blocks into a coherent whole, leaving that task to architects and developers. True, you can use design patterns such as Factory, Abstract Factory, Builder, Decorator, and Service Locator to compose the various classes and object instances that make up an application. However, these patterns are simply that: best practices given a name, with a description of what the pattern does, where to apply it, the problems it addresses, and so forth. Patterns are formalized best practices that you must implement yourself in your application.

The Spring Framework Inversion of Control (IoC) component addresses this concern by providing a formalized means of composing disparate components into a fully working application ready for use. The Spring Framework codifies formalized design patterns as first-class objects that you can integrate into your own application(s). Numerous organizations and institutions use the Spring Framework in this manner to engineer robust, maintainable applications.

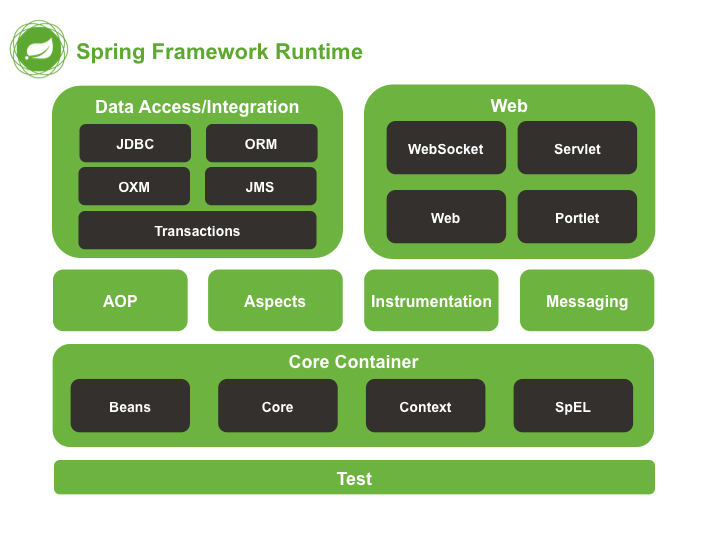

The Spring Framework consists of features organized into about 20 modules. These modules are grouped into Core Container, Data Access/Integration, Web, AOP (Aspect Oriented Programming), Instrumentation, and Test, as shown in the following diagram.

The Core Container consists of the Core, Beans, Context, and Expression Language modules.

The Core and Beans modules provide the fundamental parts of

the framework, including the IoC and Dependency Injection features. The BeanFactory is

a sophisticated implementation of the factory pattern. It removes the need for

programmatic singletons and allows you to decouple the configuration and specification

of dependencies from your actual program logic.

The Context module builds on the solid base provided by the

Core and Beans modules: it is a means to access objects in a

framework-style manner that is similar to a JNDI registry. The Context module inherits

its features from the Beans module and adds support for internationalization (using, for

example, resource bundles), event-propagation, resource-loading, and the transparent

creation of contexts by, for example, a servlet container. The Context module also

supports Java EE features such as EJB, JMX ,and basic remoting. The ApplicationContext

interface is the focal point of the Context module.

The Expression Language module provides a powerful expression language for querying and manipulating an object graph at runtime. It is an extension of the unified expression language (unified EL) as specified in the JSP 2.1 specification. The language supports setting and getting property values, property assignment, method invocation, accessing the context of arrays, collections and indexers, logical and arithmetic operators, named variables, and retrieval of objects by name from Spring’s IoC container. It also supports list projection and selection as well as common list aggregations.

The Data Access/Integration layer consists of the JDBC, ORM, OXM, JMS and Transaction modules.

The JDBC module provides a JDBC-abstraction layer that removes the need to do tedious JDBC coding and parsing of database-vendor specific error codes.

The ORM module provides integration layers for popular object-relational mapping APIs, including JPA, JDO, and Hibernate. Using the ORM package you can use all of these O/R-mapping frameworks in combination with all of the other features Spring offers, such as the simple declarative transaction management feature mentioned previously.

The OXM module provides an abstraction layer that supports Object/XML mapping implementations for JAXB, Castor, XMLBeans, JiBX and XStream.

The Java Messaging Service (JMS) module contains features for producing and consuming messages.

The Transaction module supports programmatic and declarative transaction management for classes that implement special interfaces and for all your POJOs (plain old Java objects).

The Web layer consists of the Web, Web-Servlet, WebSocket and Web-Portlet modules.

Spring’s Web module provides basic web-oriented integration features such as multipart file-upload functionality and the initialization of the IoC container using servlet listeners and a web-oriented application context. It also contains the web-related parts of Spring’s remoting support.

The Web-Servlet module contains Spring’s model-view-controller (MVC) implementation for web applications. Spring’s MVC framework provides a clean separation between domain model code and web forms, and integrates with all the other features of the Spring Framework.

The Web-Portlet module provides the MVC implementation to be used in a portlet environment and mirrors the functionality of Web-Servlet module.

Spring’s AOP module provides an AOP Alliance-compliant aspect-oriented programming implementation allowing you to define, for example, method-interceptors and pointcuts to cleanly decouple code that implements functionality that should be separated. Using source-level metadata functionality, you can also incorporate behavioral information into your code, in a manner similar to that of .NET attributes.

The separate Aspects module provides integration with AspectJ.

The Instrumentation module provides class instrumentation support and classloader implementations to be used in certain application servers.

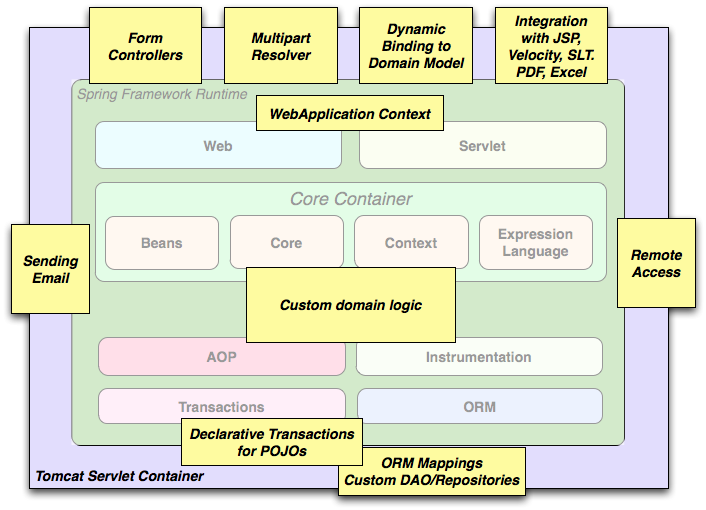

The building blocks described previously make Spring a logical choice in many scenarios, from applets to full-fledged enterprise applications that use Spring’s transaction management functionality and web framework integration.

Spring’s declarative transaction management features make

the web application fully transactional, just as it would be if you used EJB

container-managed transactions. All your custom business logic can be implemented with

simple POJOs and managed by Spring’s IoC container. Additional services include support

for sending email and validation that is independent of the web layer, which lets you

choose where to execute validation rules. Spring’s ORM support is integrated with JPA,

Hibernate and and JDO; for example, when using Hibernate, you can continue to use

your existing mapping files and standard Hibernate SessionFactory configuration. Form

controllers seamlessly integrate the web-layer with the domain model, removing the need

for ActionForms or other classes that transform HTTP parameters to values for your

domain model.

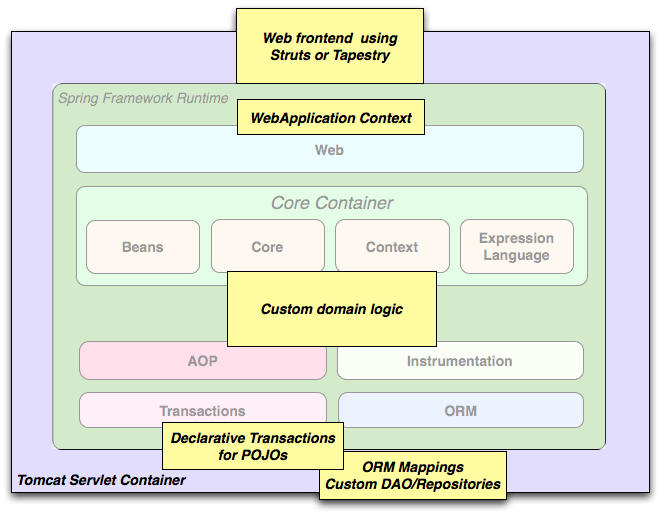

Sometimes circumstances do not allow you to completely switch to a different framework.

The Spring Framework does not force you to use everything within it; it is not an

all-or-nothing solution. Existing front-ends built with Struts, Tapestry, JSF

or other UI frameworks can be integrated with a Spring-based middle-tier, which allows

you to use Spring transaction features. You simply need to wire up your business logic

using an ApplicationContext and use a WebApplicationContext to integrate your web

layer.

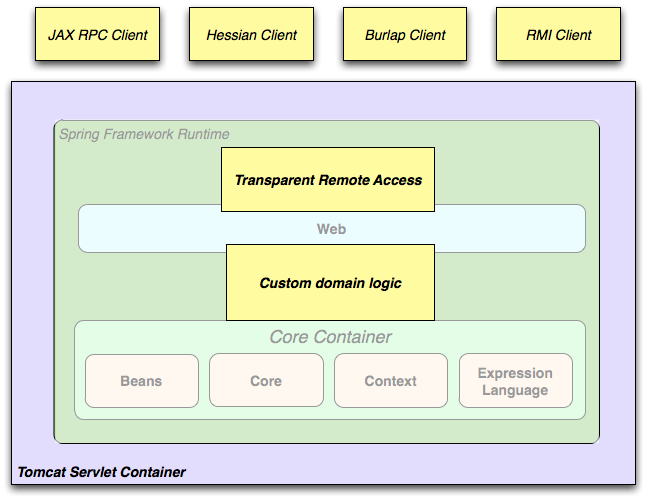

When you need to access existing code through web services, you can use Spring’s

Hessian-, Burlap-, Rmi- or JaxRpcProxyFactory classes. Enabling remote access to

existing applications is not difficult.

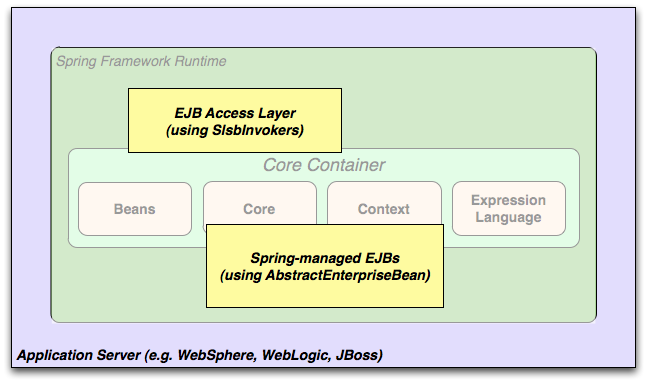

The Spring Framework also provides an access and abstraction layer for Enterprise JavaBeans, enabling you to reuse your existing POJOs and wrap them in stateless session beans for use in scalable, fail-safe web applications that might need declarative security.

Dependency management and dependency injection are different things. To get those nice

features of Spring into your application (like dependency injection) you need to

assemble all the libraries needed (jar files) and get them onto your classpath at

runtime, and possibly at compile time. These dependencies are not virtual components

that are injected, but physical resources in a file system (typically). The process of

dependency management involves locating those resources, storing them and adding them to

classpaths. Dependencies can be direct (e.g. my application depends on Spring at

runtime), or indirect (e.g. my application depends on commons-dbcp which depends on

commons-pool). The indirect dependencies are also known as "transitive" and it is

those dependencies that are hardest to identify and manage.

If you are going to use Spring you need to get a copy of the jar libraries that comprise

the pieces of Spring that you need. To make this easier Spring is packaged as a set of

modules that separate the dependencies as much as possible, so for example if you don’t

want to write a web application you don’t need the spring-web modules. To refer to

Spring library modules in this guide we use a shorthand naming convention spring-* or

spring-*.jar, where * represents the short name for the module (e.g. spring-core,

spring-webmvc, spring-jms, etc.). The actual jar file name that you use is normally

the module name concatenated with the version number

(e.g. spring-core-4.0.0.RELEASE.jar).

Each release of the Spring Framework will publish artifacts to the following places:

-

Maven Central, which is the default repository that Maven queries, and does not

require any special configuration to use. Many of the common libraries that Spring

depends on also are available from Maven Central and a large section of the Spring

community uses Maven for dependency management, so this is convenient for them. The

names of the jars here are in the form

spring-*-<version>.jarand the Maven groupId isorg.springframework. - In a public Maven repository hosted specifically for Spring. In addition to the final GA releases, this repository also hosts development snapshots and milestones. The jar file names are in the same form as Maven Central, so this is a useful place to get development versions of Spring to use with other libraries deployed in Maven Central. This repository also contains a bundle distribution zip file that contains all Spring jars bundled together for easy download.

So the first thing you need to decide is how to manage your dependencies: we generally recommend the use of an automated system like Maven, Gradle or Ivy, but you can also do it manually by downloading all the jars yourself. We provide detailed instructions later in this chapter.

Although Spring provides integration and support for a huge range of enterprise and other external tools, it intentionally keeps its mandatory dependencies to an absolute minimum: you shouldn’t have to locate and download (even automatically) a large number of jar libraries in order to use Spring for simple use cases. For basic dependency injection there is only one mandatory external dependency, and that is for logging (see below for a more detailed description of logging options).

Next we outline the basic steps needed to configure an application that depends on Spring, first with Maven and then with Gradle and finally using Ivy. In all cases, if anything is unclear, refer to the documentation of your dependency management system, or look at some sample code - Spring itself uses Gradle to manage dependencies when it is building, and our samples mostly use Gradle or Maven.

If you are using Maven for dependency management you don’t even need to supply the logging dependency explicitly. For example, to create an application context and use dependency injection to configure an application, your Maven dependencies will look like this:

<dependencies> <dependency> <groupId>org.springframework</groupId> <artifactId>spring-context</artifactId> <version>4.0.0.RELEASE</version> <scope>runtime</scope> </dependency> </dependencies>

That’s it. Note the scope can be declared as runtime if you don’t need to compile against Spring APIs, which is typically the case for basic dependency injection use cases.

The example above works with the Maven Central repository. To use the Spring Maven repository (e.g. for milestones or developer snapshots), you need to specify the repository location in your Maven configuration. For full releases:

<repositories> <repository> <id>io.spring.repo.maven.release</id> <url>http://repo.spring.io/release/</url> <snapshots><enabled>false</enabled></snapshots> </repository> </repositories>

For milestones:

<repositories> <repository> <id>io.spring.repo.maven.milestone</id> <url>http://repo.spring.io/milestone/</url> <snapshots><enabled>false</enabled></snapshots> </repository> </repositories>

And for snapshots:

<repositories> <repository> <id>io.spring.repo.maven.snapshot</id> <url>http://repo.spring.io/snapshot/</url> <snapshots><enabled>true</enabled></snapshots> </repository> </repositories>

It is possible to accidentally mix different versions of Spring JARs when using Maven. For example, you may find that a third-party library, or another Spring project, pulls in a transitive dependency to an older release. If you forget to explicitly declare a direct dependency yourself, all sorts of unexpected issues can arise.

To overcome such problems Maven supports the concept of a "bill of materials" (BOM)

dependency. You can import the spring-framework-bom in your dependencyManagement

section to ensure that all spring dependencies (both direct and transitive) are at

the same version.

<dependencyManagement> <dependencies> <dependency> <groupId>org.springframework</groupId> <artifactId>spring-framework-bom</artifactId> <version>4.0.0.RELEASE</version> <type>pom</type> <scope>import</scope> </dependency> </dependencies> </dependencyManagement>

An added benefit of using the BOM is that you no longer need to specify the <version>

attribute when depending on Spring Framework artifacts:

<dependencies> <dependency> <groupId>org.springframework</groupId> <artifactId>spring-context</artifactId> </dependency> <dependency> <groupId>org.springframework</groupId> <artifactId>spring-web</artifactId> </dependency> <dependencies>

To use the Spring repository with the Gradle build system,

include the appropriate URL in the repositories section:

repositories {

mavenCentral()

// and optionally...

maven { url "http://repo.spring.io/release" }

}

You can change the repositories URL from /release to /milestone or /snapshot as

appropriate. Once a repository has been configured, you can declare dependencies in the

usual Gradle way:

dependencies {

compile("org.springframework:spring-context:4.0.0.RELEASE")

testCompile("org.springframework:spring-test:4.0.0.RELEASE")

}

If you prefer to use Ivy to manage dependencies then there are similar configuration options.

To configure Ivy to point to the Spring repository add the following resolver to your

ivysettings.xml:

<resolvers> <ibiblio name="io.spring.repo.maven.release" m2compatible="true" root="http://repo.spring.io/release/"/> </resolvers>

You can change the root URL from /release/ to /milestone/ or /snapshot/ as

appropriate.

Once configured, you can add dependencies in the usual way. For example (in ivy.xml):

<dependency org="org.springframework" name="spring-core" rev="4.0.0.RELEASE" conf="compile->runtime"/>

Although using a build system that supports dependency management is the recommended way to obtain the Spring Framework, it is still possible to download a distribution zip file.

Distribution zips are published to the Spring Maven Repository (this is just for our convenience, you don’t need Maven or any other build system in order to download them).

To download a distribution zip open a web browser to

http://repo.spring.io/release/org/springframework/spring and select the appropriate

subfolder for the version that you want. Distribution files end -dist.zip, for example

spring-framework-4.0.0.RELEASE-RELEASE-dist.zip. Distributions are also published

for milestones and

snapshots.

Logging is a very important dependency for Spring because a) it is the only mandatory external dependency, b) everyone likes to see some output from the tools they are using, and c) Spring integrates with lots of other tools all of which have also made a choice of logging dependency. One of the goals of an application developer is often to have unified logging configured in a central place for the whole application, including all external components. This is more difficult than it might have been since there are so many choices of logging framework.

The mandatory logging dependency in Spring is the Jakarta Commons Logging API (JCL). We

compile against JCL and we also make JCL Log objects visible for classes that extend

the Spring Framework. It’s important to users that all versions of Spring use the same

logging library: migration is easy because backwards compatibility is preserved even

with applications that extend Spring. The way we do this is to make one of the modules

in Spring depend explicitly on commons-logging (the canonical implementation of JCL),

and then make all the other modules depend on that at compile time. If you are using

Maven for example, and wondering where you picked up the dependency on

commons-logging, then it is from Spring and specifically from the central module

called spring-core.

The nice thing about commons-logging is that you don’t need anything else to make your

application work. It has a runtime discovery algorithm that looks for other logging

frameworks in well known places on the classpath and uses one that it thinks is

appropriate (or you can tell it which one if you need to). If nothing else is available

you get pretty nice looking logs just from the JDK (java.util.logging or JUL for short).

You should find that your Spring application works and logs happily to the console out

of the box in most situations, and that’s important.

Unfortunately, the runtime discovery algorithm in commons-logging, while convenient

for the end-user, is problematic. If we could turn back the clock and start Spring now

as a new project it would use a different logging dependency. The first choice would

probably be the Simple Logging Facade for Java ( SLF4J), which is

also used by a lot of other tools that people use with Spring inside their applications.

Switching off commons-logging is easy: just make sure it isn’t on the classpath at

runtime. In Maven terms you exclude the dependency, and because of the way that the

Spring dependencies are declared, you only have to do that once.

<dependencies> <dependency> <groupId>org.springframework</groupId> <artifactId>spring-context</artifactId> <version>4.0.0.RELEASE</version> <scope>runtime</scope> <exclusions> <exclusion> <groupId>commons-logging</groupId> <artifactId>commons-logging</artifactId> </exclusion> </exclusions> </dependency> </dependencies>

Now this application is probably broken because there is no implementation of the JCL API on the classpath, so to fix it a new one has to be provided. In the next section we show you how to provide an alternative implementation of JCL using SLF4J as an example.

SLF4J is a cleaner dependency and more efficient at runtime than commons-logging

because it uses compile-time bindings instead of runtime discovery of the other logging

frameworks it integrates. This also means that you have to be more explicit about what

you want to happen at runtime, and declare it or configure it accordingly. SLF4J

provides bindings to many common logging frameworks, so you can usually choose one that

you already use, and bind to that for configuration and management.

SLF4J provides bindings to many common logging frameworks, including JCL, and it also

does the reverse: bridges between other logging frameworks and itself. So to use SLF4J

with Spring you need to replace the commons-logging dependency with the SLF4J-JCL

bridge. Once you have done that then logging calls from within Spring will be translated

into logging calls to the SLF4J API, so if other libraries in your application use that

API, then you have a single place to configure and manage logging.

A common choice might be to bridge Spring to SLF4J, and then provide explicit binding

from SLF4J to Log4J. You need to supply 4 dependencies (and exclude the existing

commons-logging): the bridge, the SLF4J API, the binding to Log4J, and the Log4J

implementation itself. In Maven you would do that like this

<dependencies> <dependency> <groupId>org.springframework</groupId> <artifactId>spring-context</artifactId> <version>4.0.0.RELEASE</version> <scope>runtime</scope> <exclusions> <exclusion> <groupId>commons-logging</groupId> <artifactId>commons-logging</artifactId> </exclusion> </exclusions> </dependency> <dependency> <groupId>org.slf4j</groupId> <artifactId>jcl-over-slf4j</artifactId> <version>1.5.8</version> <scope>runtime</scope> </dependency> <dependency> <groupId>org.slf4j</groupId> <artifactId>slf4j-api</artifactId> <version>1.5.8</version> <scope>runtime</scope> </dependency> <dependency> <groupId>org.slf4j</groupId> <artifactId>slf4j-log4j12</artifactId> <version>1.5.8</version> <scope>runtime</scope> </dependency> <dependency> <groupId>log4j</groupId> <artifactId>log4j</artifactId> <version>1.2.14</version> <scope>runtime</scope> </dependency> </dependencies>

That might seem like a lot of dependencies just to get some logging. Well it is, but it

is optional, and it should behave better than the vanilla commons-logging with

respect to classloader issues, notably if you are in a strict container like an OSGi

platform. Allegedly there is also a performance benefit because the bindings are at

compile-time not runtime.

A more common choice amongst SLF4J users, which uses fewer steps and generates fewer

dependencies, is to bind directly to Logback. This removes the

extra binding step because Logback implements SLF4J directly, so you only need to depend

on two libraries not four ( jcl-over-slf4j and logback). If you do that you might

also need to exclude the slf4j-api dependency from other external dependencies (not

Spring), because you only want one version of that API on the classpath.

Many people use Log4j as a logging framework for configuration and management purposes. It’s efficient and well-established, and in fact it’s what we use at runtime when we build and test Spring. Spring also provides some utilities for configuring and initializing Log4j, so it has an optional compile-time dependency on Log4j in some modules.

To make Log4j work with the default JCL dependency ( commons-logging) all you need to

do is put Log4j on the classpath, and provide it with a configuration file (

log4j.properties or log4j.xml in the root of the classpath). So for Maven users this

is your dependency declaration:

<dependencies> <dependency> <groupId>org.springframework</groupId> <artifactId>spring-context</artifactId> <version>4.0.0.RELEASE</version> <scope>runtime</scope> </dependency> <dependency> <groupId>log4j</groupId> <artifactId>log4j</artifactId> <version>1.2.14</version> <scope>runtime</scope> </dependency> </dependencies>

And here’s a sample log4j.properties for logging to the console:

log4j.rootCategory=INFO, stdout

log4j.appender.stdout=org.apache.log4j.ConsoleAppender

log4j.appender.stdout.layout=org.apache.log4j.PatternLayout

log4j.appender.stdout.layout.ConversionPattern=%d{ABSOLUTE} %5p %t %c{2}:%L - %m%n

log4j.category.org.springframework.beans.factory=DEBUG

Many people run their Spring applications in a container that itself provides an

implementation of JCL. IBM Websphere Application Server (WAS) is the archetype. This

often causes problems, and unfortunately there is no silver bullet solution; simply

excluding commons-logging from your application is not enough in most situations.

To be clear about this: the problems reported are usually not with JCL per se, or even

with commons-logging: rather they are to do with binding commons-logging to another

framework (often Log4J). This can fail because commons-logging changed the way they do

the runtime discovery in between the older versions (1.0) found in some containers and

the modern versions that most people use now (1.1). Spring does not use any unusual

parts of the JCL API, so nothing breaks there, but as soon as Spring or your application

tries to do any logging you can find that the bindings to Log4J are not working.

In such cases with WAS the easiest thing to do is to invert the class loader hierarchy (IBM calls it "parent last") so that the application controls the JCL dependency, not the container. That option isn’t always open, but there are plenty of other suggestions in the public domain for alternative approaches, and your mileage may vary depending on the exact version and feature set of the container.