This part of the reference documentation covers all of those technologies that are absolutely integral to the Spring Framework.

Foremost amongst these is the Spring Framework’s Inversion of Control (IoC) container. A thorough treatment of the Spring Framework’s IoC container is closely followed by comprehensive coverage of Spring’s Aspect-Oriented Programming (AOP) technologies. The Spring Framework has its own AOP framework, which is conceptually easy to understand, and which successfully addresses the 80% sweet spot of AOP requirements in Java enterprise programming.

Coverage of Spring’s integration with AspectJ (currently the richest - in terms of features - and certainly most mature AOP implementation in the Java enterprise space) is also provided.

1. The IoC container

1.1. Introduction to the Spring IoC container and beans

This chapter covers the Spring Framework implementation of the Inversion of Control (IoC) [1] principle. IoC is also known as dependency injection (DI). It is a process whereby objects define their dependencies, that is, the other objects they work with, only through constructor arguments, arguments to a factory method, or properties that are set on the object instance after it is constructed or returned from a factory method. The container then injects those dependencies when it creates the bean. This process is fundamentally the inverse, hence the name Inversion of Control (IoC), of the bean itself controlling the instantiation or location of its dependencies by using direct construction of classes, or a mechanism such as the Service Locator pattern.

The org.springframework.beans and org.springframework.context packages are the basis

for Spring Framework’s IoC container. The

BeanFactory

interface provides an advanced configuration mechanism capable of managing any type of

object.

ApplicationContext

is a sub-interface of BeanFactory. It adds easier integration with Spring’s AOP

features; message resource handling (for use in internationalization), event

publication; and application-layer specific contexts such as the WebApplicationContext

for use in web applications.

In short, the BeanFactory provides the configuration framework and basic

functionality, and the ApplicationContext adds more enterprise-specific functionality.

The ApplicationContext is a complete superset of the BeanFactory, and is used

exclusively in this chapter in descriptions of Spring’s IoC container. For more

information on using the BeanFactory instead of the ApplicationContext, refer to

The BeanFactory.

In Spring, the objects that form the backbone of your application and that are managed by the Spring IoC container are called beans. A bean is an object that is instantiated, assembled, and otherwise managed by a Spring IoC container. Otherwise, a bean is simply one of many objects in your application. Beans, and the dependencies among them, are reflected in the configuration metadata used by a container.

1.2. Container overview

The interface org.springframework.context.ApplicationContext represents the Spring IoC

container and is responsible for instantiating, configuring, and assembling the

aforementioned beans. The container gets its instructions on what objects to

instantiate, configure, and assemble by reading configuration metadata. The

configuration metadata is represented in XML, Java annotations, or Java code. It allows

you to express the objects that compose your application and the rich interdependencies

between such objects.

Several implementations of the ApplicationContext interface are supplied

out-of-the-box with Spring. In standalone applications it is common to create an

instance of

ClassPathXmlApplicationContext

or FileSystemXmlApplicationContext.

While XML has been the traditional format for defining configuration metadata you can

instruct the container to use Java annotations or code as the metadata format by

providing a small amount of XML configuration to declaratively enable support for these

additional metadata formats.

In most application scenarios, explicit user code is not required to instantiate one or

more instances of a Spring IoC container. For example, in a web application scenario, a

simple eight (or so) lines of boilerplate web descriptor XML in the web.xml file

of the application will typically suffice (see Convenient ApplicationContext instantiation for web applications). If you are using the

Spring Tool Suite Eclipse-powered development

environment this boilerplate configuration can be easily created with few mouse clicks or

keystrokes.

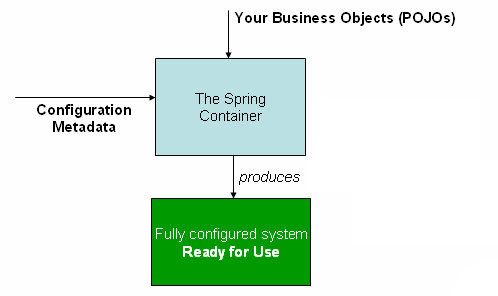

The following diagram is a high-level view of how Spring works. Your application classes

are combined with configuration metadata so that after the ApplicationContext is

created and initialized, you have a fully configured and executable system or

application.

1.2.1. Configuration metadata

As the preceding diagram shows, the Spring IoC container consumes a form of configuration metadata; this configuration metadata represents how you as an application developer tell the Spring container to instantiate, configure, and assemble the objects in your application.

Configuration metadata is traditionally supplied in a simple and intuitive XML format, which is what most of this chapter uses to convey key concepts and features of the Spring IoC container.

|

XML-based metadata is not the only allowed form of configuration metadata. The Spring IoC container itself is totally decoupled from the format in which this configuration metadata is actually written. These days many developers choose Java-based configuration for their Spring applications. |

For information about using other forms of metadata with the Spring container, see:

-

Annotation-based configuration: Spring 2.5 introduced support for annotation-based configuration metadata.

-

Java-based configuration: Starting with Spring 3.0, many features provided by the Spring JavaConfig project became part of the core Spring Framework. Thus you can define beans external to your application classes by using Java rather than XML files. To use these new features, see the

@Configuration,@Bean,@Importand@DependsOnannotations.

Spring configuration consists of at least one and typically more than one bean

definition that the container must manage. XML-based configuration metadata shows these

beans configured as <bean/> elements inside a top-level <beans/> element. Java

configuration typically uses @Bean annotated methods within a @Configuration class.

These bean definitions correspond to the actual objects that make up your application.

Typically you define service layer objects, data access objects (DAOs), presentation

objects such as Struts Action instances, infrastructure objects such as Hibernate

SessionFactories, JMS Queues, and so forth. Typically one does not configure

fine-grained domain objects in the container, because it is usually the responsibility

of DAOs and business logic to create and load domain objects. However, you can use

Spring’s integration with AspectJ to configure objects that have been created outside

the control of an IoC container. See Using AspectJ to

dependency-inject domain objects with Spring.

The following example shows the basic structure of XML-based configuration metadata:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<beans xmlns="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans"

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans

http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans/spring-beans.xsd">

<bean id="..." class="...">

<!-- collaborators and configuration for this bean go here -->

</bean>

<bean id="..." class="...">

<!-- collaborators and configuration for this bean go here -->

</bean>

<!-- more bean definitions go here -->

</beans>The id attribute is a string that you use to identify the individual bean definition.

The class attribute defines the type of the bean and uses the fully qualified

classname. The value of the id attribute refers to collaborating objects. The XML for

referring to collaborating objects is not shown in this example; see

Dependencies for more information.

1.2.2. Instantiating a container

Instantiating a Spring IoC container is straightforward. The location path or paths

supplied to an ApplicationContext constructor are actually resource strings that allow

the container to load configuration metadata from a variety of external resources such

as the local file system, from the Java CLASSPATH, and so on.

ApplicationContext context = new ClassPathXmlApplicationContext("services.xml", "daos.xml");|

After you learn about Spring’s IoC container, you may want to know more about Spring’s

|

The following example shows the service layer objects (services.xml) configuration file:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<beans xmlns="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans"

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans

http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans/spring-beans.xsd">

<!-- services -->

<bean id="petStore" class="org.springframework.samples.jpetstore.services.PetStoreServiceImpl">

<property name="accountDao" ref="accountDao"/>

<property name="itemDao" ref="itemDao"/>

<!-- additional collaborators and configuration for this bean go here -->

</bean>

<!-- more bean definitions for services go here -->

</beans>The following example shows the data access objects daos.xml file:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<beans xmlns="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans"

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans

http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans/spring-beans.xsd">

<bean id="accountDao"

class="org.springframework.samples.jpetstore.dao.jpa.JpaAccountDao">

<!-- additional collaborators and configuration for this bean go here -->

</bean>

<bean id="itemDao" class="org.springframework.samples.jpetstore.dao.jpa.JpaItemDao">

<!-- additional collaborators and configuration for this bean go here -->

</bean>

<!-- more bean definitions for data access objects go here -->

</beans>In the preceding example, the service layer consists of the class PetStoreServiceImpl,

and two data access objects of the type JpaAccountDao and JpaItemDao (based

on the JPA Object/Relational mapping standard). The property name element refers to the

name of the JavaBean property, and the ref element refers to the name of another bean

definition. This linkage between id and ref elements expresses the dependency between

collaborating objects. For details of configuring an object’s dependencies, see

Dependencies.

Composing XML-based configuration metadata

It can be useful to have bean definitions span multiple XML files. Often each individual XML configuration file represents a logical layer or module in your architecture.

You can use the application context constructor to load bean definitions from all these

XML fragments. This constructor takes multiple Resource locations, as was shown in the

previous section. Alternatively, use one or more occurrences of the <import/> element

to load bean definitions from another file or files. For example:

<beans>

<import resource="services.xml"/>

<import resource="resources/messageSource.xml"/>

<import resource="/resources/themeSource.xml"/>

<bean id="bean1" class="..."/>

<bean id="bean2" class="..."/>

</beans>In the preceding example, external bean definitions are loaded from three files:

services.xml, messageSource.xml, and themeSource.xml. All location paths are

relative to the definition file doing the importing, so services.xml must be in the

same directory or classpath location as the file doing the importing, while

messageSource.xml and themeSource.xml must be in a resources location below the

location of the importing file. As you can see, a leading slash is ignored, but given

that these paths are relative, it is better form not to use the slash at all. The

contents of the files being imported, including the top level <beans/> element, must

be valid XML bean definitions according to the Spring Schema.

|

It is possible, but not recommended, to reference files in parent directories using a relative "../" path. Doing so creates a dependency on a file that is outside the current application. In particular, this reference is not recommended for "classpath:" URLs (for example, "classpath:../services.xml"), where the runtime resolution process chooses the "nearest" classpath root and then looks into its parent directory. Classpath configuration changes may lead to the choice of a different, incorrect directory. You can always use fully qualified resource locations instead of relative paths: for example, "file:C:/config/services.xml" or "classpath:/config/services.xml". However, be aware that you are coupling your application’s configuration to specific absolute locations. It is generally preferable to keep an indirection for such absolute locations, for example, through "${…}" placeholders that are resolved against JVM system properties at runtime. |

The import directive is a feature provided by the beans namespace itself. Further configuration features beyond plain bean definitions are available in a selection of XML namespaces provided by Spring, e.g. the "context" and the "util" namespace.

The Groovy Bean Definition DSL

As a further example for externalized configuration metadata, bean definitions can also be expressed in Spring’s Groovy Bean Definition DSL, as known from the Grails framework. Typically, such configuration will live in a ".groovy" file with a structure as follows:

beans {

dataSource(BasicDataSource) {

driverClassName = "org.hsqldb.jdbcDriver"

url = "jdbc:hsqldb:mem:grailsDB"

username = "sa"

password = ""

settings = [mynew:"setting"]

}

sessionFactory(SessionFactory) {

dataSource = dataSource

}

myService(MyService) {

nestedBean = { AnotherBean bean ->

dataSource = dataSource

}

}

}This configuration style is largely equivalent to XML bean definitions and even supports Spring’s XML configuration namespaces. It also allows for importing XML bean definition files through an "importBeans" directive.

1.2.3. Using the container

The ApplicationContext is the interface for an advanced factory capable of maintaining

a registry of different beans and their dependencies. Using the method T getBean(String

name, Class<T> requiredType) you can retrieve instances of your beans.

The ApplicationContext enables you to read bean definitions and access them as follows:

// create and configure beans

ApplicationContext context = new ClassPathXmlApplicationContext("services.xml", "daos.xml");

// retrieve configured instance

PetStoreService service = context.getBean("petStore", PetStoreService.class);

// use configured instance

List<String> userList = service.getUsernameList();With Groovy configuration, bootstrapping looks very similar, just a different context implementation class which is Groovy-aware (but also understands XML bean definitions):

ApplicationContext context = new GenericGroovyApplicationContext("services.groovy", "daos.groovy");The most flexible variant is GenericApplicationContext in combination with reader

delegates, e.g. with XmlBeanDefinitionReader for XML files:

GenericApplicationContext context = new GenericApplicationContext();

new XmlBeanDefinitionReader(context).loadBeanDefinitions("services.xml", "daos.xml");

context.refresh();Or with GroovyBeanDefinitionReader for Groovy files:

GenericApplicationContext context = new GenericApplicationContext();

new GroovyBeanDefinitionReader(context).loadBeanDefinitions("services.groovy", "daos.groovy");

context.refresh();Such reader delegates can be mixed and matched on the same ApplicationContext,

reading bean definitions from diverse configuration sources, if desired.

You can then use getBean to retrieve instances of your beans. The ApplicationContext

interface has a few other methods for retrieving beans, but ideally your application

code should never use them. Indeed, your application code should have no calls to the

getBean() method at all, and thus no dependency on Spring APIs at all. For example,

Spring’s integration with web frameworks provides dependency injection for various web

framework components such as controllers and JSF-managed beans, allowing you to declare

a dependency on a specific bean through metadata (e.g. an autowiring annotation).

1.3. Bean overview

A Spring IoC container manages one or more beans. These beans are created with the

configuration metadata that you supply to the container, for example, in the form of XML

<bean/> definitions.

Within the container itself, these bean definitions are represented as BeanDefinition

objects, which contain (among other information) the following metadata:

-

A package-qualified class name: typically the actual implementation class of the bean being defined.

-

Bean behavioral configuration elements, which state how the bean should behave in the container (scope, lifecycle callbacks, and so forth).

-

References to other beans that are needed for the bean to do its work; these references are also called collaborators or dependencies.

-

Other configuration settings to set in the newly created object, for example, the number of connections to use in a bean that manages a connection pool, or the size limit of the pool.

This metadata translates to a set of properties that make up each bean definition.

| Property | Explained in… |

|---|---|

class |

|

name |

|

scope |

|

constructor arguments |

|

properties |

|

autowiring mode |

|

lazy-initialization mode |

|

initialization method |

|

destruction method |

In addition to bean definitions that contain information on how to create a specific

bean, the ApplicationContext implementations also permit the registration of existing

objects that are created outside the container, by users. This is done by accessing the

ApplicationContext’s BeanFactory via the method getBeanFactory() which returns the

BeanFactory implementation DefaultListableBeanFactory. DefaultListableBeanFactory

supports this registration through the methods registerSingleton(..) and

registerBeanDefinition(..). However, typical applications work solely with beans

defined through metadata bean definitions.

|

Bean metadata and manually supplied singleton instances need to be registered as early as possible, in order for the container to properly reason about them during autowiring and other introspection steps. While overriding of existing metadata and existing singleton instances is supported to some degree, the registration of new beans at runtime (concurrently with live access to factory) is not officially supported and may lead to concurrent access exceptions and/or inconsistent state in the bean container. |

1.3.1. Naming beans

Every bean has one or more identifiers. These identifiers must be unique within the container that hosts the bean. A bean usually has only one identifier, but if it requires more than one, the extra ones can be considered aliases.

In XML-based configuration metadata, you use the id and/or name attributes

to specify the bean identifier(s). The id attribute allows you to specify

exactly one id. Conventionally these names are alphanumeric ('myBean',

'fooService', etc.), but may contain special characters as well. If you want to

introduce other aliases to the bean, you can also specify them in the name

attribute, separated by a comma (,), semicolon (;), or white space. As a

historical note, in versions prior to Spring 3.1, the id attribute was

defined as an xsd:ID type, which constrained possible characters. As of 3.1,

it is defined as an xsd:string type. Note that bean id uniqueness is still

enforced by the container, though no longer by XML parsers.

You are not required to supply a name or id for a bean. If no name or id is supplied

explicitly, the container generates a unique name for that bean. However, if you want to

refer to that bean by name, through the use of the ref element or

Service Locator style lookup, you must provide a name.

Motivations for not supplying a name are related to using inner

beans and autowiring collaborators.

|

With component scanning in the classpath, Spring generates bean names for unnamed

components, following the rules above: essentially, taking the simple class name

and turning its initial character to lower-case. However, in the (unusual) special

case when there is more than one character and both the first and second characters

are upper case, the original casing gets preserved. These are the same rules as

defined by |

Aliasing a bean outside the bean definition

In a bean definition itself, you can supply more than one name for the bean, by using a

combination of up to one name specified by the id attribute, and any number of other

names in the name attribute. These names can be equivalent aliases to the same bean,

and are useful for some situations, such as allowing each component in an application to

refer to a common dependency by using a bean name that is specific to that component

itself.

Specifying all aliases where the bean is actually defined is not always adequate,

however. It is sometimes desirable to introduce an alias for a bean that is defined

elsewhere. This is commonly the case in large systems where configuration is split

amongst each subsystem, each subsystem having its own set of object definitions. In

XML-based configuration metadata, you can use the <alias/> element to accomplish this.

<alias name="fromName" alias="toName"/>In this case, a bean in the same container which is named fromName, may also,

after the use of this alias definition, be referred to as toName.

For example, the configuration metadata for subsystem A may refer to a DataSource via

the name subsystemA-dataSource. The configuration metadata for subsystem B may refer to

a DataSource via the name subsystemB-dataSource. When composing the main application

that uses both these subsystems the main application refers to the DataSource via the

name myApp-dataSource. To have all three names refer to the same object you add to the

MyApp configuration metadata the following aliases definitions:

<alias name="subsystemA-dataSource" alias="subsystemB-dataSource"/>

<alias name="subsystemA-dataSource" alias="myApp-dataSource" />Now each component and the main application can refer to the dataSource through a name that is unique and guaranteed not to clash with any other definition (effectively creating a namespace), yet they refer to the same bean.

1.3.2. Instantiating beans

A bean definition essentially is a recipe for creating one or more objects. The container looks at the recipe for a named bean when asked, and uses the configuration metadata encapsulated by that bean definition to create (or acquire) an actual object.

If you use XML-based configuration metadata, you specify the type (or class) of object

that is to be instantiated in the class attribute of the <bean/> element. This

class attribute, which internally is a Class property on a BeanDefinition

instance, is usually mandatory. (For exceptions, see

Instantiation using an instance factory method and Bean definition inheritance.)

You use the Class property in one of two ways:

-

Typically, to specify the bean class to be constructed in the case where the container itself directly creates the bean by calling its constructor reflectively, somewhat equivalent to Java code using the

newoperator. -

To specify the actual class containing the

staticfactory method that will be invoked to create the object, in the less common case where the container invokes astaticfactory method on a class to create the bean. The object type returned from the invocation of thestaticfactory method may be the same class or another class entirely.

Instantiation with a constructor

When you create a bean by the constructor approach, all normal classes are usable by and compatible with Spring. That is, the class being developed does not need to implement any specific interfaces or to be coded in a specific fashion. Simply specifying the bean class should suffice. However, depending on what type of IoC you use for that specific bean, you may need a default (empty) constructor.

The Spring IoC container can manage virtually any class you want it to manage; it is not limited to managing true JavaBeans. Most Spring users prefer actual JavaBeans with only a default (no-argument) constructor and appropriate setters and getters modeled after the properties in the container. You can also have more exotic non-bean-style classes in your container. If, for example, you need to use a legacy connection pool that absolutely does not adhere to the JavaBean specification, Spring can manage it as well.

With XML-based configuration metadata you can specify your bean class as follows:

<bean id="exampleBean" class="examples.ExampleBean"/>

<bean name="anotherExample" class="examples.ExampleBeanTwo"/>For details about the mechanism for supplying arguments to the constructor (if required) and setting object instance properties after the object is constructed, see Injecting Dependencies.

Instantiation with a static factory method

When defining a bean that you create with a static factory method, you use the class

attribute to specify the class containing the static factory method and an attribute

named factory-method to specify the name of the factory method itself. You should be

able to call this method (with optional arguments as described later) and return a live

object, which subsequently is treated as if it had been created through a constructor.

One use for such a bean definition is to call static factories in legacy code.

The following bean definition specifies that the bean will be created by calling a

factory-method. The definition does not specify the type (class) of the returned object,

only the class containing the factory method. In this example, the createInstance()

method must be a static method.

<bean id="clientService"

class="examples.ClientService"

factory-method="createInstance"/>public class ClientService {

private static ClientService clientService = new ClientService();

private ClientService() {}

public static ClientService createInstance() {

return clientService;

}

}For details about the mechanism for supplying (optional) arguments to the factory method and setting object instance properties after the object is returned from the factory, see Dependencies and configuration in detail.

Instantiation using an instance factory method

Similar to instantiation through a static

factory method, instantiation with an instance factory method invokes a non-static

method of an existing bean from the container to create a new bean. To use this

mechanism, leave the class attribute empty, and in the factory-bean attribute,

specify the name of a bean in the current (or parent/ancestor) container that contains

the instance method that is to be invoked to create the object. Set the name of the

factory method itself with the factory-method attribute.

<!-- the factory bean, which contains a method called createInstance() -->

<bean id="serviceLocator" class="examples.DefaultServiceLocator">

<!-- inject any dependencies required by this locator bean -->

</bean>

<!-- the bean to be created via the factory bean -->

<bean id="clientService"

factory-bean="serviceLocator"

factory-method="createClientServiceInstance"/>public class DefaultServiceLocator {

private static ClientService clientService = new ClientServiceImpl();

public ClientService createClientServiceInstance() {

return clientService;

}

}One factory class can also hold more than one factory method as shown here:

<bean id="serviceLocator" class="examples.DefaultServiceLocator">

<!-- inject any dependencies required by this locator bean -->

</bean>

<bean id="clientService"

factory-bean="serviceLocator"

factory-method="createClientServiceInstance"/>

<bean id="accountService"

factory-bean="serviceLocator"

factory-method="createAccountServiceInstance"/>public class DefaultServiceLocator {

private static ClientService clientService = new ClientServiceImpl();

private static AccountService accountService = new AccountServiceImpl();

public ClientService createClientServiceInstance() {

return clientService;

}

public AccountService createAccountServiceInstance() {

return accountService;

}

}This approach shows that the factory bean itself can be managed and configured through dependency injection (DI). See Dependencies and configuration in detail.

|

In Spring documentation, factory bean refers to a bean that is configured in the

Spring container that will create objects through an

instance or

static factory method. By contrast,

|

1.4. Dependencies

A typical enterprise application does not consist of a single object (or bean in the Spring parlance). Even the simplest application has a few objects that work together to present what the end-user sees as a coherent application. This next section explains how you go from defining a number of bean definitions that stand alone to a fully realized application where objects collaborate to achieve a goal.

1.4.1. Dependency Injection

Dependency injection (DI) is a process whereby objects define their dependencies, that is, the other objects they work with, only through constructor arguments, arguments to a factory method, or properties that are set on the object instance after it is constructed or returned from a factory method. The container then injects those dependencies when it creates the bean. This process is fundamentally the inverse, hence the name Inversion of Control (IoC), of the bean itself controlling the instantiation or location of its dependencies on its own by using direct construction of classes, or the Service Locator pattern.

Code is cleaner with the DI principle and decoupling is more effective when objects are provided with their dependencies. The object does not look up its dependencies, and does not know the location or class of the dependencies. As such, your classes become easier to test, in particular when the dependencies are on interfaces or abstract base classes, which allow for stub or mock implementations to be used in unit tests.

DI exists in two major variants, Constructor-based dependency injection and Setter-based dependency injection.

Constructor-based dependency injection

Constructor-based DI is accomplished by the container invoking a constructor with a

number of arguments, each representing a dependency. Calling a static factory method

with specific arguments to construct the bean is nearly equivalent, and this discussion

treats arguments to a constructor and to a static factory method similarly. The

following example shows a class that can only be dependency-injected with constructor

injection. Notice that there is nothing special about this class, it is a POJO that

has no dependencies on container specific interfaces, base classes or annotations.

public class SimpleMovieLister {

// the SimpleMovieLister has a dependency on a MovieFinder

private MovieFinder movieFinder;

// a constructor so that the Spring container can inject a MovieFinder

public SimpleMovieLister(MovieFinder movieFinder) {

this.movieFinder = movieFinder;

}

// business logic that actually uses the injected MovieFinder is omitted...

}Constructor argument resolution

Constructor argument resolution matching occurs using the argument’s type. If no potential ambiguity exists in the constructor arguments of a bean definition, then the order in which the constructor arguments are defined in a bean definition is the order in which those arguments are supplied to the appropriate constructor when the bean is being instantiated. Consider the following class:

package x.y;

public class Foo {

public Foo(Bar bar, Baz baz) {

// ...

}

}No potential ambiguity exists, assuming that Bar and Baz classes are not related by

inheritance. Thus the following configuration works fine, and you do not need to specify

the constructor argument indexes and/or types explicitly in the <constructor-arg/>

element.

<beans>

<bean id="foo" class="x.y.Foo">

<constructor-arg ref="bar"/>

<constructor-arg ref="baz"/>

</bean>

<bean id="bar" class="x.y.Bar"/>

<bean id="baz" class="x.y.Baz"/>

</beans>When another bean is referenced, the type is known, and matching can occur (as was the

case with the preceding example). When a simple type is used, such as

<value>true</value>, Spring cannot determine the type of the value, and so cannot match

by type without help. Consider the following class:

package examples;

public class ExampleBean {

// Number of years to calculate the Ultimate Answer

private int years;

// The Answer to Life, the Universe, and Everything

private String ultimateAnswer;

public ExampleBean(int years, String ultimateAnswer) {

this.years = years;

this.ultimateAnswer = ultimateAnswer;

}

}In the preceding scenario, the container can use type matching with simple types if

you explicitly specify the type of the constructor argument using the type attribute.

For example:

<bean id="exampleBean" class="examples.ExampleBean">

<constructor-arg type="int" value="7500000"/>

<constructor-arg type="java.lang.String" value="42"/>

</bean>Use the index attribute to specify explicitly the index of constructor arguments. For

example:

<bean id="exampleBean" class="examples.ExampleBean">

<constructor-arg index="0" value="7500000"/>

<constructor-arg index="1" value="42"/>

</bean>In addition to resolving the ambiguity of multiple simple values, specifying an index resolves ambiguity where a constructor has two arguments of the same type. Note that the index is 0 based.

You can also use the constructor parameter name for value disambiguation:

<bean id="exampleBean" class="examples.ExampleBean">

<constructor-arg name="years" value="7500000"/>

<constructor-arg name="ultimateAnswer" value="42"/>

</bean>Keep in mind that to make this work out of the box your code must be compiled with the debug flag enabled so that Spring can look up the parameter name from the constructor. If you can’t compile your code with debug flag (or don’t want to) you can use @ConstructorProperties JDK annotation to explicitly name your constructor arguments. The sample class would then have to look as follows:

package examples;

public class ExampleBean {

// Fields omitted

@ConstructorProperties({"years", "ultimateAnswer"})

public ExampleBean(int years, String ultimateAnswer) {

this.years = years;

this.ultimateAnswer = ultimateAnswer;

}

}Setter-based dependency injection

Setter-based DI is accomplished by the container calling setter methods on your

beans after invoking a no-argument constructor or no-argument static factory method to

instantiate your bean.

The following example shows a class that can only be dependency-injected using pure setter injection. This class is conventional Java. It is a POJO that has no dependencies on container specific interfaces, base classes or annotations.

public class SimpleMovieLister {

// the SimpleMovieLister has a dependency on the MovieFinder

private MovieFinder movieFinder;

// a setter method so that the Spring container can inject a MovieFinder

public void setMovieFinder(MovieFinder movieFinder) {

this.movieFinder = movieFinder;

}

// business logic that actually uses the injected MovieFinder is omitted...

}The ApplicationContext supports constructor-based and setter-based DI for the beans it

manages. It also supports setter-based DI after some dependencies have already been

injected through the constructor approach. You configure the dependencies in the form of

a BeanDefinition, which you use in conjunction with PropertyEditor instances to

convert properties from one format to another. However, most Spring users do not work

with these classes directly (i.e., programmatically) but rather with XML bean

definitions, annotated components (i.e., classes annotated with @Component,

@Controller, etc.), or @Bean methods in Java-based @Configuration classes. These

sources are then converted internally into instances of BeanDefinition and used to

load an entire Spring IoC container instance.

Dependency resolution process

The container performs bean dependency resolution as follows:

-

The

ApplicationContextis created and initialized with configuration metadata that describes all the beans. Configuration metadata can be specified via XML, Java code, or annotations. -

For each bean, its dependencies are expressed in the form of properties, constructor arguments, or arguments to the static-factory method if you are using that instead of a normal constructor. These dependencies are provided to the bean, when the bean is actually created.

-

Each property or constructor argument is an actual definition of the value to set, or a reference to another bean in the container.

-

Each property or constructor argument which is a value is converted from its specified format to the actual type of that property or constructor argument. By default Spring can convert a value supplied in string format to all built-in types, such as

int,long,String,boolean, etc.

The Spring container validates the configuration of each bean as the container is created. However, the bean properties themselves are not set until the bean is actually created. Beans that are singleton-scoped and set to be pre-instantiated (the default) are created when the container is created. Scopes are defined in Bean scopes. Otherwise, the bean is created only when it is requested. Creation of a bean potentially causes a graph of beans to be created, as the bean’s dependencies and its dependencies' dependencies (and so on) are created and assigned. Note that resolution mismatches among those dependencies may show up late, i.e. on first creation of the affected bean.

You can generally trust Spring to do the right thing. It detects configuration problems,

such as references to non-existent beans and circular dependencies, at container

load-time. Spring sets properties and resolves dependencies as late as possible, when

the bean is actually created. This means that a Spring container which has loaded

correctly can later generate an exception when you request an object if there is a

problem creating that object or one of its dependencies. For example, the bean throws an

exception as a result of a missing or invalid property. This potentially delayed

visibility of some configuration issues is why ApplicationContext implementations by

default pre-instantiate singleton beans. At the cost of some upfront time and memory to

create these beans before they are actually needed, you discover configuration issues

when the ApplicationContext is created, not later. You can still override this default

behavior so that singleton beans will lazy-initialize, rather than be pre-instantiated.

If no circular dependencies exist, when one or more collaborating beans are being injected into a dependent bean, each collaborating bean is totally configured prior to being injected into the dependent bean. This means that if bean A has a dependency on bean B, the Spring IoC container completely configures bean B prior to invoking the setter method on bean A. In other words, the bean is instantiated (if not a pre-instantiated singleton), its dependencies are set, and the relevant lifecycle methods (such as a configured init method or the InitializingBean callback method) are invoked.

Examples of dependency injection

The following example uses XML-based configuration metadata for setter-based DI. A small part of a Spring XML configuration file specifies some bean definitions:

<bean id="exampleBean" class="examples.ExampleBean">

<!-- setter injection using the nested ref element -->

<property name="beanOne">

<ref bean="anotherExampleBean"/>

</property>

<!-- setter injection using the neater ref attribute -->

<property name="beanTwo" ref="yetAnotherBean"/>

<property name="integerProperty" value="1"/>

</bean>

<bean id="anotherExampleBean" class="examples.AnotherBean"/>

<bean id="yetAnotherBean" class="examples.YetAnotherBean"/>public class ExampleBean {

private AnotherBean beanOne;

private YetAnotherBean beanTwo;

private int i;

public void setBeanOne(AnotherBean beanOne) {

this.beanOne = beanOne;

}

public void setBeanTwo(YetAnotherBean beanTwo) {

this.beanTwo = beanTwo;

}

public void setIntegerProperty(int i) {

this.i = i;

}

}In the preceding example, setters are declared to match against the properties specified in the XML file. The following example uses constructor-based DI:

<bean id="exampleBean" class="examples.ExampleBean">

<!-- constructor injection using the nested ref element -->

<constructor-arg>

<ref bean="anotherExampleBean"/>

</constructor-arg>

<!-- constructor injection using the neater ref attribute -->

<constructor-arg ref="yetAnotherBean"/>

<constructor-arg type="int" value="1"/>

</bean>

<bean id="anotherExampleBean" class="examples.AnotherBean"/>

<bean id="yetAnotherBean" class="examples.YetAnotherBean"/>public class ExampleBean {

private AnotherBean beanOne;

private YetAnotherBean beanTwo;

private int i;

public ExampleBean(

AnotherBean anotherBean, YetAnotherBean yetAnotherBean, int i) {

this.beanOne = anotherBean;

this.beanTwo = yetAnotherBean;

this.i = i;

}

}The constructor arguments specified in the bean definition will be used as arguments to

the constructor of the ExampleBean.

Now consider a variant of this example, where instead of using a constructor, Spring is

told to call a static factory method to return an instance of the object:

<bean id="exampleBean" class="examples.ExampleBean" factory-method="createInstance">

<constructor-arg ref="anotherExampleBean"/>

<constructor-arg ref="yetAnotherBean"/>

<constructor-arg value="1"/>

</bean>

<bean id="anotherExampleBean" class="examples.AnotherBean"/>

<bean id="yetAnotherBean" class="examples.YetAnotherBean"/>public class ExampleBean {

// a private constructor

private ExampleBean(...) {

...

}

// a static factory method; the arguments to this method can be

// considered the dependencies of the bean that is returned,

// regardless of how those arguments are actually used.

public static ExampleBean createInstance (

AnotherBean anotherBean, YetAnotherBean yetAnotherBean, int i) {

ExampleBean eb = new ExampleBean (...);

// some other operations...

return eb;

}

}Arguments to the static factory method are supplied via <constructor-arg/> elements,

exactly the same as if a constructor had actually been used. The type of the class being

returned by the factory method does not have to be of the same type as the class that

contains the static factory method, although in this example it is. An instance

(non-static) factory method would be used in an essentially identical fashion (aside

from the use of the factory-bean attribute instead of the class attribute), so

details will not be discussed here.

1.4.2. Dependencies and configuration in detail

As mentioned in the previous section, you can define bean properties and constructor

arguments as references to other managed beans (collaborators), or as values defined

inline. Spring’s XML-based configuration metadata supports sub-element types within its

<property/> and <constructor-arg/> elements for this purpose.

Straight values (primitives, Strings, and so on)

The value attribute of the <property/> element specifies a property or constructor

argument as a human-readable string representation. Spring’s

conversion service is used to convert these

values from a String to the actual type of the property or argument.

<bean id="myDataSource" class="org.apache.commons.dbcp.BasicDataSource" destroy-method="close">

<!-- results in a setDriverClassName(String) call -->

<property name="driverClassName" value="com.mysql.jdbc.Driver"/>

<property name="url" value="jdbc:mysql://localhost:3306/mydb"/>

<property name="username" value="root"/>

<property name="password" value="masterkaoli"/>

</bean>The following example uses the p-namespace for even more succinct XML configuration.

<beans xmlns="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans"

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xmlns:p="http://www.springframework.org/schema/p"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans

http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans/spring-beans.xsd">

<bean id="myDataSource" class="org.apache.commons.dbcp.BasicDataSource"

destroy-method="close"

p:driverClassName="com.mysql.jdbc.Driver"

p:url="jdbc:mysql://localhost:3306/mydb"

p:username="root"

p:password="masterkaoli"/>

</beans>The preceding XML is more succinct; however, typos are discovered at runtime rather than design time, unless you use an IDE such as IntelliJ IDEA or the Spring Tool Suite (STS) that support automatic property completion when you create bean definitions. Such IDE assistance is highly recommended.

You can also configure a java.util.Properties instance as:

<bean id="mappings"

class="org.springframework.beans.factory.config.PropertyPlaceholderConfigurer">

<!-- typed as a java.util.Properties -->

<property name="properties">

<value>

jdbc.driver.className=com.mysql.jdbc.Driver

jdbc.url=jdbc:mysql://localhost:3306/mydb

</value>

</property>

</bean>The Spring container converts the text inside the <value/> element into a

java.util.Properties instance by using the JavaBeans PropertyEditor mechanism. This

is a nice shortcut, and is one of a few places where the Spring team do favor the use of

the nested <value/> element over the value attribute style.

The idref element

The idref element is simply an error-proof way to pass the id (string value - not

a reference) of another bean in the container to a <constructor-arg/> or <property/>

element.

<bean id="theTargetBean" class="..."/>

<bean id="theClientBean" class="...">

<property name="targetName">

<idref bean="theTargetBean"/>

</property>

</bean>The above bean definition snippet is exactly equivalent (at runtime) to the following snippet:

<bean id="theTargetBean" class="..." />

<bean id="client" class="...">

<property name="targetName" value="theTargetBean"/>

</bean>The first form is preferable to the second, because using the idref tag allows the

container to validate at deployment time that the referenced, named bean actually

exists. In the second variation, no validation is performed on the value that is passed

to the targetName property of the client bean. Typos are only discovered (with most

likely fatal results) when the client bean is actually instantiated. If the client

bean is a prototype bean, this typo and the resulting exception

may only be discovered long after the container is deployed.

|

The |

A common place (at least in versions earlier than Spring 2.0) where the <idref/> element

brings value is in the configuration of AOP interceptors in a

ProxyFactoryBean bean definition. Using <idref/> elements when you specify the

interceptor names prevents you from misspelling an interceptor id.

References to other beans (collaborators)

The ref element is the final element inside a <constructor-arg/> or <property/>

definition element. Here you set the value of the specified property of a bean to be a

reference to another bean (a collaborator) managed by the container. The referenced bean

is a dependency of the bean whose property will be set, and it is initialized on demand

as needed before the property is set. (If the collaborator is a singleton bean, it may

be initialized already by the container.) All references are ultimately a reference to

another object. Scoping and validation depend on whether you specify the id/name of the

other object through the bean, local, or parent attributes.

Specifying the target bean through the bean attribute of the <ref/> tag is the most

general form, and allows creation of a reference to any bean in the same container or

parent container, regardless of whether it is in the same XML file. The value of the

bean attribute may be the same as the id attribute of the target bean, or as one of

the values in the name attribute of the target bean.

<ref bean="someBean"/>Specifying the target bean through the parent attribute creates a reference to a bean

that is in a parent container of the current container. The value of the parent

attribute may be the same as either the id attribute of the target bean, or one of the

values in the name attribute of the target bean, and the target bean must be in a

parent container of the current one. You use this bean reference variant mainly when you

have a hierarchy of containers and you want to wrap an existing bean in a parent

container with a proxy that will have the same name as the parent bean.

<!-- in the parent context -->

<bean id="accountService" class="com.foo.SimpleAccountService">

<!-- insert dependencies as required as here -->

</bean><!-- in the child (descendant) context -->

<bean id="accountService" <!-- bean name is the same as the parent bean -->

class="org.springframework.aop.framework.ProxyFactoryBean">

<property name="target">

<ref parent="accountService"/> <!-- notice how we refer to the parent bean -->

</property>

<!-- insert other configuration and dependencies as required here -->

</bean>|

The |

Inner beans

A <bean/> element inside the <property/> or <constructor-arg/> elements defines a

so-called inner bean.

<bean id="outer" class="...">

<!-- instead of using a reference to a target bean, simply define the target bean inline -->

<property name="target">

<bean class="com.example.Person"> <!-- this is the inner bean -->

<property name="name" value="Fiona Apple"/>

<property name="age" value="25"/>

</bean>

</property>

</bean>An inner bean definition does not require a defined id or name; if specified, the container

does not use such a value as an identifier. The container also ignores the scope flag on

creation: Inner beans are always anonymous and they are always created with the outer

bean. It is not possible to inject inner beans into collaborating beans other than into

the enclosing bean or to access them independently.

As a corner case, it is possible to receive destruction callbacks from a custom scope, e.g. for a request-scoped inner bean contained within a singleton bean: The creation of the inner bean instance will be tied to its containing bean, but destruction callbacks allow it to participate in the request scope’s lifecycle. This is not a common scenario; inner beans typically simply share their containing bean’s scope.

Collections

In the <list/>, <set/>, <map/>, and <props/> elements, you set the properties

and arguments of the Java Collection types List, Set, Map, and Properties,

respectively.

<bean id="moreComplexObject" class="example.ComplexObject">

<!-- results in a setAdminEmails(java.util.Properties) call -->

<property name="adminEmails">

<props>

<prop key="administrator">[email protected]</prop>

<prop key="support">[email protected]</prop>

<prop key="development">[email protected]</prop>

</props>

</property>

<!-- results in a setSomeList(java.util.List) call -->

<property name="someList">

<list>

<value>a list element followed by a reference</value>

<ref bean="myDataSource" />

</list>

</property>

<!-- results in a setSomeMap(java.util.Map) call -->

<property name="someMap">

<map>

<entry key="an entry" value="just some string"/>

<entry key ="a ref" value-ref="myDataSource"/>

</map>

</property>

<!-- results in a setSomeSet(java.util.Set) call -->

<property name="someSet">

<set>

<value>just some string</value>

<ref bean="myDataSource" />

</set>

</property>

</bean>The value of a map key or value, or a set value, can also again be any of the following elements:

bean | ref | idref | list | set | map | props | value | nullCollection merging

The Spring container also supports the merging of collections. An application

developer can define a parent-style <list/>, <map/>, <set/> or <props/> element,

and have child-style <list/>, <map/>, <set/> or <props/> elements inherit and

override values from the parent collection. That is, the child collection’s values are

the result of merging the elements of the parent and child collections, with the child’s

collection elements overriding values specified in the parent collection.

This section on merging discusses the parent-child bean mechanism. Readers unfamiliar with parent and child bean definitions may wish to read the relevant section before continuing.

The following example demonstrates collection merging:

<beans>

<bean id="parent" abstract="true" class="example.ComplexObject">

<property name="adminEmails">

<props>

<prop key="administrator">[email protected]</prop>

<prop key="support">[email protected]</prop>

</props>

</property>

</bean>

<bean id="child" parent="parent">

<property name="adminEmails">

<!-- the merge is specified on the child collection definition -->

<props merge="true">

<prop key="sales">[email protected]</prop>

<prop key="support">[email protected]</prop>

</props>

</property>

</bean>

<beans>Notice the use of the merge=true attribute on the <props/> element of the

adminEmails property of the child bean definition. When the child bean is resolved

and instantiated by the container, the resulting instance has an adminEmails

Properties collection that contains the result of the merging of the child’s

adminEmails collection with the parent’s adminEmails collection.

The child Properties collection’s value set inherits all property elements from the

parent <props/>, and the child’s value for the support value overrides the value in

the parent collection.

This merging behavior applies similarly to the <list/>, <map/>, and <set/>

collection types. In the specific case of the <list/> element, the semantics

associated with the List collection type, that is, the notion of an ordered

collection of values, is maintained; the parent’s values precede all of the child list’s

values. In the case of the Map, Set, and Properties collection types, no ordering

exists. Hence no ordering semantics are in effect for the collection types that underlie

the associated Map, Set, and Properties implementation types that the container

uses internally.

Limitations of collection merging

You cannot merge different collection types (such as a Map and a List), and if you

do attempt to do so an appropriate Exception is thrown. The merge attribute must be

specified on the lower, inherited, child definition; specifying the merge attribute on

a parent collection definition is redundant and will not result in the desired merging.

Strongly-typed collection

With the introduction of generic types in Java 5, you can use strongly typed collections.

That is, it is possible to declare a Collection type such that it can only contain

String elements (for example). If you are using Spring to dependency-inject a

strongly-typed Collection into a bean, you can take advantage of Spring’s

type-conversion support such that the elements of your strongly-typed Collection

instances are converted to the appropriate type prior to being added to the Collection.

public class Foo {

private Map<String, Float> accounts;

public void setAccounts(Map<String, Float> accounts) {

this.accounts = accounts;

}

}<beans>

<bean id="foo" class="x.y.Foo">

<property name="accounts">

<map>

<entry key="one" value="9.99"/>

<entry key="two" value="2.75"/>

<entry key="six" value="3.99"/>

</map>

</property>

</bean>

</beans>When the accounts property of the foo bean is prepared for injection, the generics

information about the element type of the strongly-typed Map<String, Float> is

available by reflection. Thus Spring’s type conversion infrastructure recognizes the

various value elements as being of type Float, and the string values 9.99, 2.75, and

3.99 are converted into an actual Float type.

Null and empty string values

Spring treats empty arguments for properties and the like as empty Strings. The

following XML-based configuration metadata snippet sets the email property to the empty

String value ("").

<bean class="ExampleBean">

<property name="email" value=""/>

</bean>The preceding example is equivalent to the following Java code:

exampleBean.setEmail("");The <null/> element handles null values. For example:

<bean class="ExampleBean">

<property name="email">

<null/>

</property>

</bean>The above configuration is equivalent to the following Java code:

exampleBean.setEmail(null);XML shortcut with the p-namespace

The p-namespace enables you to use the bean element’s attributes, instead of nested

<property/> elements, to describe your property values and/or collaborating beans.

Spring supports extensible configuration formats

with namespaces,

which are based on an XML Schema definition. The beans configuration format discussed in this

chapter is defined in an XML Schema document. However, the p-namespace is not defined in

an XSD file and exists only in the core of Spring.

The following example shows two XML snippets that resolve to the same result: The first uses standard XML format and the second uses the p-namespace.

<beans xmlns="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans"

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xmlns:p="http://www.springframework.org/schema/p"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans

http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans/spring-beans.xsd">

<bean name="classic" class="com.example.ExampleBean">

<property name="email" value="[email protected]"/>

</bean>

<bean name="p-namespace" class="com.example.ExampleBean"

p:email="[email protected]"/>

</beans>The example shows an attribute in the p-namespace called email in the bean definition. This tells Spring to include a property declaration. As previously mentioned, the p-namespace does not have a schema definition, so you can set the name of the attribute to the property name.

This next example includes two more bean definitions that both have a reference to another bean:

<beans xmlns="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans"

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xmlns:p="http://www.springframework.org/schema/p"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans

http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans/spring-beans.xsd">

<bean name="john-classic" class="com.example.Person">

<property name="name" value="John Doe"/>

<property name="spouse" ref="jane"/>

</bean>

<bean name="john-modern"

class="com.example.Person"

p:name="John Doe"

p:spouse-ref="jane"/>

<bean name="jane" class="com.example.Person">

<property name="name" value="Jane Doe"/>

</bean>

</beans>As you can see, this example includes not only a property value using the p-namespace,

but also uses a special format to declare property references. Whereas the first bean

definition uses <property name="spouse" ref="jane"/> to create a reference from bean

john to bean jane, the second bean definition uses p:spouse-ref="jane" as an

attribute to do the exact same thing. In this case spouse is the property name,

whereas the -ref part indicates that this is not a straight value but rather a

reference to another bean.

|

The p-namespace is not as flexible as the standard XML format. For example, the format

for declaring property references clashes with properties that end in |

XML shortcut with the c-namespace

Similar to the XML shortcut with the p-namespace, the c-namespace, newly introduced in Spring

3.1, allows usage of inlined attributes for configuring the constructor arguments rather

then nested constructor-arg elements.

Let’s review the examples from Constructor-based dependency injection with the c: namespace:

<beans xmlns="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans"

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xmlns:c="http://www.springframework.org/schema/c"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans

http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans/spring-beans.xsd">

<bean id="bar" class="x.y.Bar"/>

<bean id="baz" class="x.y.Baz"/>

<!-- traditional declaration -->

<bean id="foo" class="x.y.Foo">

<constructor-arg ref="bar"/>

<constructor-arg ref="baz"/>

<constructor-arg value="[email protected]"/>

</bean>

<!-- c-namespace declaration -->

<bean id="foo" class="x.y.Foo" c:bar-ref="bar" c:baz-ref="baz" c:email="[email protected]"/>

</beans>The c: namespace uses the same conventions as the p: one (trailing -ref for bean

references) for setting the constructor arguments by their names. And just as well, it

needs to be declared even though it is not defined in an XSD schema (but it exists

inside the Spring core).

For the rare cases where the constructor argument names are not available (usually if the bytecode was compiled without debugging information), one can use fallback to the argument indexes:

<!-- c-namespace index declaration -->

<bean id="foo" class="x.y.Foo" c:_0-ref="bar" c:_1-ref="baz"/>|

Due to the XML grammar, the index notation requires the presence of the leading |

In practice, the constructor resolution mechanism is quite efficient in matching arguments so unless one really needs to, we recommend using the name notation through-out your configuration.

Compound property names

You can use compound or nested property names when you set bean properties, as long as

all components of the path except the final property name are not null. Consider the

following bean definition.

<bean id="foo" class="foo.Bar">

<property name="fred.bob.sammy" value="123" />

</bean>The foo bean has a fred property, which has a bob property, which has a sammy

property, and that final sammy property is being set to the value 123. In order for

this to work, the fred property of foo, and the bob property of fred must not be

null after the bean is constructed, or a NullPointerException is thrown.

1.4.3. Using depends-on

If a bean is a dependency of another that usually means that one bean is set as a

property of another. Typically you accomplish this with the <ref/>

element in XML-based configuration metadata. However, sometimes dependencies between

beans are less direct; for example, a static initializer in a class needs to be

triggered, such as database driver registration. The depends-on attribute can

explicitly force one or more beans to be initialized before the bean using this element

is initialized. The following example uses the depends-on attribute to express a

dependency on a single bean:

<bean id="beanOne" class="ExampleBean" depends-on="manager"/>

<bean id="manager" class="ManagerBean" />To express a dependency on multiple beans, supply a list of bean names as the value of

the depends-on attribute, with commas, whitespace and semicolons, used as valid

delimiters:

<bean id="beanOne" class="ExampleBean" depends-on="manager,accountDao">

<property name="manager" ref="manager" />

</bean>

<bean id="manager" class="ManagerBean" />

<bean id="accountDao" class="x.y.jdbc.JdbcAccountDao" />|

The |

1.4.4. Lazy-initialized beans

By default, ApplicationContext implementations eagerly create and configure all

singleton beans as part of the initialization

process. Generally, this pre-instantiation is desirable, because errors in the

configuration or surrounding environment are discovered immediately, as opposed to hours

or even days later. When this behavior is not desirable, you can prevent

pre-instantiation of a singleton bean by marking the bean definition as

lazy-initialized. A lazy-initialized bean tells the IoC container to create a bean

instance when it is first requested, rather than at startup.

In XML, this behavior is controlled by the lazy-init attribute on the <bean/>

element; for example:

<bean id="lazy" class="com.foo.ExpensiveToCreateBean" lazy-init="true"/>

<bean name="not.lazy" class="com.foo.AnotherBean"/>When the preceding configuration is consumed by an ApplicationContext, the bean named

lazy is not eagerly pre-instantiated when the ApplicationContext is starting up,

whereas the not.lazy bean is eagerly pre-instantiated.

However, when a lazy-initialized bean is a dependency of a singleton bean that is

not lazy-initialized, the ApplicationContext creates the lazy-initialized bean at

startup, because it must satisfy the singleton’s dependencies. The lazy-initialized bean

is injected into a singleton bean elsewhere that is not lazy-initialized.

You can also control lazy-initialization at the container level by using the

default-lazy-init attribute on the <beans/> element; for example:

<beans default-lazy-init="true">

<!-- no beans will be pre-instantiated... -->

</beans>1.4.5. Autowiring collaborators

The Spring container can autowire relationships between collaborating beans. You can

allow Spring to resolve collaborators (other beans) automatically for your bean by

inspecting the contents of the ApplicationContext. Autowiring has the following

advantages:

-

Autowiring can significantly reduce the need to specify properties or constructor arguments. (Other mechanisms such as a bean template discussed elsewhere in this chapter are also valuable in this regard.)

-

Autowiring can update a configuration as your objects evolve. For example, if you need to add a dependency to a class, that dependency can be satisfied automatically without you needing to modify the configuration. Thus autowiring can be especially useful during development, without negating the option of switching to explicit wiring when the code base becomes more stable.

When using XML-based configuration metadata [2], you specify autowire

mode for a bean definition with the autowire attribute of the <bean/> element. The

autowiring functionality has four modes. You specify autowiring per bean and thus

can choose which ones to autowire.

| Mode | Explanation |

|---|---|

no |

(Default) No autowiring. Bean references must be defined via a |

byName |

Autowiring by property name. Spring looks for a bean with the same name as the

property that needs to be autowired. For example, if a bean definition is set to

autowire by name, and it contains a master property (that is, it has a

setMaster(..) method), Spring looks for a bean definition named |

byType |

Allows a property to be autowired if exactly one bean of the property type exists in the container. If more than one exists, a fatal exception is thrown, which indicates that you may not use byType autowiring for that bean. If there are no matching beans, nothing happens; the property is not set. |

constructor |

Analogous to byType, but applies to constructor arguments. If there is not exactly one bean of the constructor argument type in the container, a fatal error is raised. |

With byType or constructor autowiring mode, you can wire arrays and

typed-collections. In such cases all autowire candidates within the container that

match the expected type are provided to satisfy the dependency. You can autowire

strongly-typed Maps if the expected key type is String. An autowired Maps values will

consist of all bean instances that match the expected type, and the Maps keys will

contain the corresponding bean names.

You can combine autowire behavior with dependency checking, which is performed after autowiring completes.

Limitations and disadvantages of autowiring

Autowiring works best when it is used consistently across a project. If autowiring is not used in general, it might be confusing to developers to use it to wire only one or two bean definitions.

Consider the limitations and disadvantages of autowiring:

-

Explicit dependencies in

propertyandconstructor-argsettings always override autowiring. You cannot autowire so-called simple properties such as primitives,Strings, andClasses(and arrays of such simple properties). This limitation is by-design. -

Autowiring is less exact than explicit wiring. Although, as noted in the above table, Spring is careful to avoid guessing in case of ambiguity that might have unexpected results, the relationships between your Spring-managed objects are no longer documented explicitly.

-

Wiring information may not be available to tools that may generate documentation from a Spring container.

-

Multiple bean definitions within the container may match the type specified by the setter method or constructor argument to be autowired. For arrays, collections, or Maps, this is not necessarily a problem. However for dependencies that expect a single value, this ambiguity is not arbitrarily resolved. If no unique bean definition is available, an exception is thrown.

In the latter scenario, you have several options:

-

Abandon autowiring in favor of explicit wiring.

-

Avoid autowiring for a bean definition by setting its

autowire-candidateattributes tofalseas described in the next section. -

Designate a single bean definition as the primary candidate by setting the

primaryattribute of its<bean/>element totrue. -

Implement the more fine-grained control available with annotation-based configuration, as described in Annotation-based container configuration.

Excluding a bean from autowiring

On a per-bean basis, you can exclude a bean from autowiring. In Spring’s XML format, set

the autowire-candidate attribute of the <bean/> element to false; the container

makes that specific bean definition unavailable to the autowiring infrastructure

(including annotation style configurations such as @Autowired).

|

The |

You can also limit autowire candidates based on pattern-matching against bean names. The

top-level <beans/> element accepts one or more patterns within its

default-autowire-candidates attribute. For example, to limit autowire candidate status

to any bean whose name ends with Repository, provide a value of *Repository. To

provide multiple patterns, define them in a comma-separated list. An explicit value of

true or false for a bean definitions autowire-candidate attribute always takes

precedence, and for such beans, the pattern matching rules do not apply.

These techniques are useful for beans that you never want to be injected into other beans by autowiring. It does not mean that an excluded bean cannot itself be configured using autowiring. Rather, the bean itself is not a candidate for autowiring other beans.

1.4.6. Method injection

In most application scenarios, most beans in the container are singletons. When a singleton bean needs to collaborate with another singleton bean, or a non-singleton bean needs to collaborate with another non-singleton bean, you typically handle the dependency by defining one bean as a property of the other. A problem arises when the bean lifecycles are different. Suppose singleton bean A needs to use non-singleton (prototype) bean B, perhaps on each method invocation on A. The container only creates the singleton bean A once, and thus only gets one opportunity to set the properties. The container cannot provide bean A with a new instance of bean B every time one is needed.

A solution is to forego some inversion of control. You can make

bean A aware of the container by implementing the ApplicationContextAware interface,

and by making a getBean("B") call to the container ask for (a

typically new) bean B instance every time bean A needs it. The following is an example

of this approach:

// a class that uses a stateful Command-style class to perform some processing

package fiona.apple;

// Spring-API imports

import org.springframework.beans.BeansException;

import org.springframework.context.ApplicationContext;

import org.springframework.context.ApplicationContextAware;

public class CommandManager implements ApplicationContextAware {

private ApplicationContext applicationContext;

public Object process(Map commandState) {

// grab a new instance of the appropriate Command

Command command = createCommand();

// set the state on the (hopefully brand new) Command instance

command.setState(commandState);

return command.execute();

}

protected Command createCommand() {

// notice the Spring API dependency!

return this.applicationContext.getBean("command", Command.class);

}

public void setApplicationContext(

ApplicationContext applicationContext) throws BeansException {

this.applicationContext = applicationContext;

}

}The preceding is not desirable, because the business code is aware of and coupled to the Spring Framework. Method Injection, a somewhat advanced feature of the Spring IoC container, allows this use case to be handled in a clean fashion.

Lookup method injection

Lookup method injection is the ability of the container to override methods on container managed beans, to return the lookup result for another named bean in the container. The lookup typically involves a prototype bean as in the scenario described in the preceding section. The Spring Framework implements this method injection by using bytecode generation from the CGLIB library to generate dynamically a subclass that overrides the method.

|

Looking at the CommandManager class in the previous code snippet, you see that the

Spring container will dynamically override the implementation of the createCommand()

method. Your CommandManager class will not have any Spring dependencies, as can be

seen in the reworked example:

package fiona.apple;

// no more Spring imports!

public abstract class CommandManager {

public Object process(Object commandState) {

// grab a new instance of the appropriate Command interface

Command command = createCommand();

// set the state on the (hopefully brand new) Command instance

command.setState(commandState);

return command.execute();

}

// okay... but where is the implementation of this method?

protected abstract Command createCommand();

}In the client class containing the method to be injected (the CommandManager in this

case), the method to be injected requires a signature of the following form:

<public|protected> [abstract] <return-type> theMethodName(no-arguments);If the method is abstract, the dynamically-generated subclass implements the method.

Otherwise, the dynamically-generated subclass overrides the concrete method defined in