The advanced authorization capabilities within Spring Security represent one of the most compelling reasons for its popularity. Irrespective of how you choose to authenticate - whether using a Spring Security-provided mechanism and provider, or integrating with a container or other non-Spring Security authentication authority - you will find the authorization services can be used within your application in a consistent and simple way.

In this part we’ll explore the different AbstractSecurityInterceptor implementations, which were introduced in Part I.

We then move on to explore how to fine-tune authorization through use of domain access control lists.

As we saw in the technical overview, all Authentication implementations store a list of GrantedAuthority objects.

These represent the authorities that have been granted to the principal.

the GrantedAuthority objects are inserted into the Authentication object by the AuthenticationManager and are later read by AccessDecisionManager s when making authorization decisions.

GrantedAuthority is an interface with only one method:

String getAuthority();

This method allows

AccessDecisionManager s to obtain a precise String representation of the GrantedAuthority.

By returning a representation as a String, a GrantedAuthority can be easily "read" by most AccessDecisionManager s.

If a GrantedAuthority cannot be precisely represented as a String, the GrantedAuthority is considered "complex" and getAuthority() must return null.

An example of a "complex" GrantedAuthority would be an implementation that stores a list of operations and authority thresholds that apply to different customer account numbers.

Representing this complex GrantedAuthority as a String would be quite difficult, and as a result the getAuthority() method should return null.

This will indicate to any AccessDecisionManager that it will need to specifically support the GrantedAuthority implementation in order to understand its contents.

Spring Security includes one concrete GrantedAuthority implementation, SimpleGrantedAuthority.

This allows any user-specified String to be converted into a GrantedAuthority.

All AuthenticationProvider s included with the security architecture use SimpleGrantedAuthority to populate the Authentication object.

As we’ve also seen in the Technical Overview chapter, Spring Security provides interceptors which control access to secure objects such as method invocations or web requests.

A pre-invocation decision on whether the invocation is allowed to proceed is made by the AccessDecisionManager.

The AccessDecisionManager is called by the AbstractSecurityInterceptor and is responsible for making final access control decisions.

The AccessDecisionManager interface contains three methods:

void decide(Authentication authentication, Object secureObject, Collection<ConfigAttribute> attrs) throws AccessDeniedException; boolean supports(ConfigAttribute attribute); boolean supports(Class clazz);

The AccessDecisionManager's decide method is passed all the relevant information it needs in order to make an authorization decision.

In particular, passing the secure Object enables those arguments contained in the actual secure object invocation to be inspected.

For example, let’s assume the secure object was a MethodInvocation.

It would be easy to query the MethodInvocation for any Customer argument, and then implement some sort of security logic in the AccessDecisionManager to ensure the principal is permitted to operate on that customer.

Implementations are expected to throw an AccessDeniedException if access is denied.

The supports(ConfigAttribute) method is called by the AbstractSecurityInterceptor at startup time to determine if the AccessDecisionManager can process the passed ConfigAttribute.

The supports(Class) method is called by a security interceptor implementation to ensure the configured AccessDecisionManager supports the type of secure object that the security interceptor will present.

Whilst users can implement their own AccessDecisionManager to control all aspects of authorization, Spring Security includes several AccessDecisionManager implementations that are based on voting.

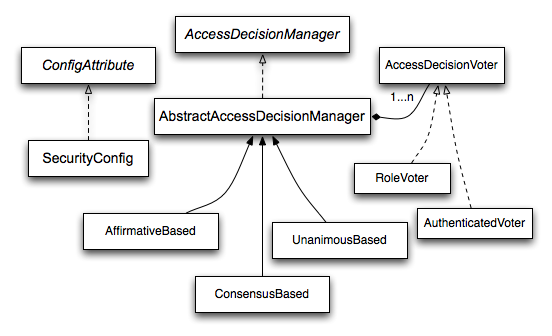

Figure 11.1, “Voting Decision Manager” illustrates the relevant classes.

Using this approach, a series of AccessDecisionVoter implementations are polled on an authorization decision.

The AccessDecisionManager then decides whether or not to throw an AccessDeniedException based on its assessment of the votes.

The AccessDecisionVoter interface has three methods:

int vote(Authentication authentication, Object object, Collection<ConfigAttribute> attrs); boolean supports(ConfigAttribute attribute); boolean supports(Class clazz);

Concrete implementations return an int, with possible values being reflected in the AccessDecisionVoter static fields ACCESS_ABSTAIN, ACCESS_DENIED and ACCESS_GRANTED.

A voting implementation will return ACCESS_ABSTAIN if it has no opinion on an authorization decision.

If it does have an opinion, it must return either ACCESS_DENIED or ACCESS_GRANTED.

There are three concrete AccessDecisionManager s provided with Spring Security that tally the votes.

The ConsensusBased implementation will grant or deny access based on the consensus of non-abstain votes.

Properties are provided to control behavior in the event of an equality of votes or if all votes are abstain.

The AffirmativeBased implementation will grant access if one or more ACCESS_GRANTED votes were received (i.e. a deny vote will be ignored, provided there was at least one grant vote).

Like the ConsensusBased implementation, there is a parameter that controls the behavior if all voters abstain.

The UnanimousBased provider expects unanimous ACCESS_GRANTED votes in order to grant access, ignoring abstains.

It will deny access if there is any ACCESS_DENIED vote.

Like the other implementations, there is a parameter that controls the behaviour if all voters abstain.

It is possible to implement a custom AccessDecisionManager that tallies votes differently.

For example, votes from a particular AccessDecisionVoter might receive additional weighting, whilst a deny vote from a particular voter may have a veto effect.

The most commonly used AccessDecisionVoter provided with Spring Security is the simple RoleVoter, which treats configuration attributes as simple role names and votes to grant access if the user has been assigned that role.

It will vote if any ConfigAttribute begins with the prefix ROLE_.

It will vote to grant access if there is a GrantedAuthority which returns a String representation (via the getAuthority() method) exactly equal to one or more ConfigAttributes starting with the prefix ROLE_.

If there is no exact match of any ConfigAttribute starting with ROLE_, the RoleVoter will vote to deny access.

If no ConfigAttribute begins with ROLE_, the voter will abstain.

Another voter which we’ve implicitly seen is the AuthenticatedVoter, which can be used to differentiate between anonymous, fully-authenticated and remember-me authenticated users.

Many sites allow certain limited access under remember-me authentication, but require a user to confirm their identity by logging in for full access.

When we’ve used the attribute IS_AUTHENTICATED_ANONYMOUSLY to grant anonymous access, this attribute was being processed by the AuthenticatedVoter.

See the Javadoc for this class for more information.

Obviously, you can also implement a custom AccessDecisionVoter and you can put just about any access-control logic you want in it.

It might be specific to your application (business-logic related) or it might implement some security administration logic.

For example, you’ll find a blog article on the Spring web site which describes how to use a voter to deny access in real-time to users whose accounts have been suspended.

Whilst the AccessDecisionManager is called by the AbstractSecurityInterceptor before proceeding with the secure object invocation, some applications need a way of modifying the object actually returned by the secure object invocation.

Whilst you could easily implement your own AOP concern to achieve this, Spring Security provides a convenient hook that has several concrete implementations that integrate with its ACL capabilities.

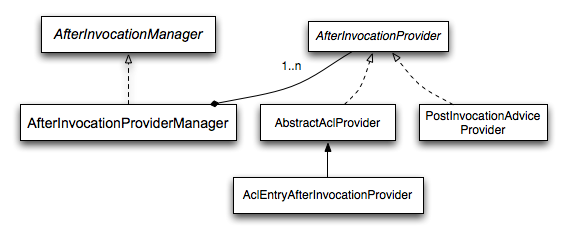

Figure 11.2, “After Invocation Implementation” illustrates Spring Security’s AfterInvocationManager and its concrete implementations.

Like many other parts of Spring Security, AfterInvocationManager has a single concrete implementation, AfterInvocationProviderManager, which polls a list of AfterInvocationProvider s.

Each AfterInvocationProvider is allowed to modify the return object or throw an AccessDeniedException.

Indeed multiple providers can modify the object, as the result of the previous provider is passed to the next in the list.

Please be aware that if you’re using AfterInvocationManager, you will still need configuration attributes that allow the MethodSecurityInterceptor's AccessDecisionManager to allow an operation.

If you’re using the typical Spring Security included AccessDecisionManager implementations, having no configuration attributes defined for a particular secure method invocation will cause each AccessDecisionVoter to abstain from voting.

In turn, if the AccessDecisionManager property “allowIfAllAbstainDecisions” is false, an AccessDeniedException will be thrown.

You may avoid this potential issue by either (i) setting “allowIfAllAbstainDecisions” to true (although this is generally not recommended) or (ii) simply ensure that there is at least one configuration attribute that an AccessDecisionVoter will vote to grant access for.

This latter (recommended) approach is usually achieved through a ROLE_USER or ROLE_AUTHENTICATED configuration attribute.

It is a common requirement that a particular role in an application should automatically "include" other roles. For example, in an application which has the concept of an "admin" and a "user" role, you may want an admin to be able to do everything a normal user can. To achieve this, you can either make sure that all admin users are also assigned the "user" role. Alternatively, you can modify every access constraint which requires the "user" role to also include the "admin" role. This can get quite complicated if you have a lot of different roles in your application.

The use of a role-hierarchy allows you to configure which roles (or authorities) should include others.

An extended version of Spring Security’s RoleVoter, RoleHierarchyVoter, is configured with a RoleHierarchy, from which it obtains all the "reachable authorities" which the user is assigned.

A typical configuration might look like this:

<bean id="roleVoter" class="org.springframework.security.access.vote.RoleHierarchyVoter"> <constructor-arg ref="roleHierarchy" /> </bean> <bean id="roleHierarchy" class="org.springframework.security.access.hierarchicalroles.RoleHierarchyImpl"> <property name="hierarchy"> <value> ROLE_ADMIN > ROLE_STAFF ROLE_STAFF > ROLE_USER ROLE_USER > ROLE_GUEST </value> </property> </bean>

Here we have four roles in a hierarchy ROLE_ADMIN ⇒ ROLE_STAFF ⇒ ROLE_USER ⇒ ROLE_GUEST.

A user who is authenticated with ROLE_ADMIN, will behave as if they have all four roles when security constraints are evaluated against an AccessDecisionManager configured with the above RoleHierarchyVoter.

The > symbol can be thought of as meaning "includes".

Role hierarchies offer a convenient means of simplifying the access-control configuration data for your application and/or reducing the number of authorities which you need to assign to a user. For more complex requirements you may wish to define a logical mapping between the specific access-rights your application requires and the roles that are assigned to users, translating between the two when loading the user information.

Prior to Spring Security 2.0, securing MethodInvocation s needed quite a lot of boiler plate configuration.

Now the recommended approach for method security is to use namespace configuration.

This way the method security infrastructure beans are configured automatically for you so you don’t really need to know about the implementation classes.

We’ll just provide a quick overview of the classes that are involved here.

Method security is enforced using a MethodSecurityInterceptor, which secures MethodInvocation s.

Depending on the configuration approach, an interceptor may be specific to a single bean or shared between multiple beans.

The interceptor uses a MethodSecurityMetadataSource instance to obtain the configuration attributes that apply to a particular method invocation.

MapBasedMethodSecurityMetadataSource is used to store configuration attributes keyed by method names (which can be wildcarded) and will be used internally when the attributes are defined in the application context using the <intercept-methods> or <protect-point> elements.

Other implementations will be used to handle annotation-based configuration.

You can of course configure a MethodSecurityIterceptor directly in your application context for use with one of Spring AOP’s proxying mechanisms:

<bean id="bankManagerSecurity" class= "org.springframework.security.access.intercept.aopalliance.MethodSecurityInterceptor"> <property name="authenticationManager" ref="authenticationManager"/> <property name="accessDecisionManager" ref="accessDecisionManager"/> <property name="afterInvocationManager" ref="afterInvocationManager"/> <property name="securityMetadataSource"> <sec:method-security-metadata-source> <sec:protect method="com.mycompany.BankManager.delete*" access="ROLE_SUPERVISOR"/> <sec:protect method="com.mycompany.BankManager.getBalance" access="ROLE_TELLER,ROLE_SUPERVISOR"/> </sec:method-security-metadata-source> </property> </bean>

The AspectJ security interceptor is very similar to the AOP Alliance security interceptor discussed in the previous section. Indeed we will only discuss the differences in this section.

The AspectJ interceptor is named AspectJSecurityInterceptor.

Unlike the AOP Alliance security interceptor, which relies on the Spring application context to weave in the security interceptor via proxying, the AspectJSecurityInterceptor is weaved in via the AspectJ compiler.

It would not be uncommon to use both types of security interceptors in the same application, with AspectJSecurityInterceptor being used for domain object instance security and the AOP Alliance MethodSecurityInterceptor being used for services layer security.

Let’s first consider how the AspectJSecurityInterceptor is configured in the Spring application context:

<bean id="bankManagerSecurity" class= "org.springframework.security.access.intercept.aspectj.AspectJMethodSecurityInterceptor"> <property name="authenticationManager" ref="authenticationManager"/> <property name="accessDecisionManager" ref="accessDecisionManager"/> <property name="afterInvocationManager" ref="afterInvocationManager"/> <property name="securityMetadataSource"> <sec:method-security-metadata-source> <sec:protect method="com.mycompany.BankManager.delete*" access="ROLE_SUPERVISOR"/> <sec:protect method="com.mycompany.BankManager.getBalance" access="ROLE_TELLER,ROLE_SUPERVISOR"/> </sec:method-security-metadata-source> </property> </bean>

As you can see, aside from the class name, the AspectJSecurityInterceptor is exactly the same as the AOP Alliance security interceptor.

Indeed the two interceptors can share the same securityMetadataSource, as the SecurityMetadataSource works with java.lang.reflect.Method s rather than an AOP library-specific class.

Of course, your access decisions have access to the relevant AOP library-specific invocation (ie MethodInvocation or JoinPoint) and as such can consider a range of addition criteria when making access decisions (such as method arguments).

Next you’ll need to define an AspectJ aspect.

For example:

package org.springframework.security.samples.aspectj; import org.springframework.security.access.intercept.aspectj.AspectJSecurityInterceptor; import org.springframework.security.access.intercept.aspectj.AspectJCallback; import org.springframework.beans.factory.InitializingBean; public aspect DomainObjectInstanceSecurityAspect implements InitializingBean { private AspectJSecurityInterceptor securityInterceptor; pointcut domainObjectInstanceExecution(): target(PersistableEntity) && execution(public * *(..)) && !within(DomainObjectInstanceSecurityAspect); Object around(): domainObjectInstanceExecution() { if (this.securityInterceptor == null) { return proceed(); } AspectJCallback callback = new AspectJCallback() { public Object proceedWithObject() { return proceed(); } }; return this.securityInterceptor.invoke(thisJoinPoint, callback); } public AspectJSecurityInterceptor getSecurityInterceptor() { return securityInterceptor; } public void setSecurityInterceptor(AspectJSecurityInterceptor securityInterceptor) { this.securityInterceptor = securityInterceptor; } public void afterPropertiesSet() throws Exception { if (this.securityInterceptor == null) throw new IllegalArgumentException("securityInterceptor required"); } } }

In the above example, the security interceptor will be applied to every instance of PersistableEntity, which is an abstract class not shown (you can use any other class or pointcut expression you like).

For those curious, AspectJCallback is needed because the proceed(); statement has special meaning only within an around() body.

The AspectJSecurityInterceptor calls this anonymous AspectJCallback class when it wants the target object to continue.

You will need to configure Spring to load the aspect and wire it with the AspectJSecurityInterceptor.

A bean declaration which achieves this is shown below:

<bean id="domainObjectInstanceSecurityAspect" class="security.samples.aspectj.DomainObjectInstanceSecurityAspect" factory-method="aspectOf"> <property name="securityInterceptor" ref="bankManagerSecurity"/> </bean>

That’s it!

Now you can create your beans from anywhere within your application, using whatever means you think fit (eg new Person();) and they will have the security interceptor applied.

Spring Security 3.0 introduced the ability to use Spring EL expressions as an authorization mechanism in addition to the simple use of configuration attributes and access-decision voters which have seen before. Expression-based access control is built on the same architecture but allows complicated Boolean logic to be encapsulated in a single expression.

Spring Security uses Spring EL for expression support and you should look at how that works if you are interested in understanding the topic in more depth. Expressions are evaluated with a "root object" as part of the evaluation context. Spring Security uses specific classes for web and method security as the root object, in order to provide built-in expressions and access to values such as the current principal.

The base class for expression root objects is SecurityExpressionRoot.

This provides some common expressions which are available in both web and method security.

Table 11.1. Common built-in expressions

| Expression | Description |

|---|---|

| Returns For example, By default if the supplied role does not start with 'ROLE_' it will be added.

This can be customized by modifying the |

| Returns For example, By default if the supplied role does not start with 'ROLE_' it will be added.

This can be customized by modifying the |

| Returns For example, |

| Returns For example, |

| Allows direct access to the principal object representing the current user |

| Allows direct access to the current |

| Always evaluates to |

| Always evaluates to |

| Returns |

| Returns |

| Returns |

| Returns |

| Returns |

| Returns |

To use expressions to secure individual URLs, you would first need to set the use-expressions attribute in the <http> element to true.

Spring Security will then expect the access attributes of the <intercept-url> elements to contain Spring EL expressions.

The expressions should evaluate to a Boolean, defining whether access should be allowed or not.

For example:

<http> <intercept-url pattern="/admin*" access="hasRole('admin') and hasIpAddress('192.168.1.0/24')"/> ... </http>

Here we have defined that the "admin" area of an application (defined by the URL pattern) should only be available to users who have the granted authority "admin" and whose IP address matches a local subnet.

We’ve already seen the built-in hasRole expression in the previous section.

The expression hasIpAddress is an additional built-in expression which is specific to web security.

It is defined by the WebSecurityExpressionRoot class, an instance of which is used as the expression root object when evaluation web-access expressions.

This object also directly exposed the HttpServletRequest object under the name request so you can invoke the request directly in an expression.

If expressions are being used, a WebExpressionVoter will be added to the AccessDecisionManager which is used by the namespace.

So if you aren’t using the namespace and want to use expressions, you will have to add one of these to your configuration.

If you wish to extend the expressions that are available, you can easily refer to any Spring Bean you expose.

For example, assuming you have a Bean with the name of webSecurity that contains the following method signature:

public class WebSecurity { public boolean check(Authentication authentication, HttpServletRequest request) { ... } }

You could refer to the method using:

<http> <intercept-url pattern="/user/**" access="@webSecurity.check(authentication,request)"/> ... </http>

or in Java configuration

http

.authorizeRequests()

.antMatchers("/user/**").access("@webSecurity.check(authentication,request)")

...

At times it is nice to be able to refer to path variables within a URL.

For example, consider a RESTful application that looks up a user by id from the URL path in the format /user/{userId}.

You can easily refer to the path variable by placing it in the pattern.

For example, if you had a Bean with the name of webSecurity that contains the following method signature:

public class WebSecurity { public boolean checkUserId(Authentication authentication, int id) { ... } }

You could refer to the method using:

<http> <intercept-url pattern="/user/{userId}/**" access="@webSecurity.checkUserId(authentication,#userId)"/> ... </http>

or in Java configuration

http

.authorizeRequests(authorizeRequests ->

authorizeRequests

.antMatchers("/user/{userId}/**").access("@webSecurity.checkUserId(authentication,#userId)")

...

);

In both configurations URLs that match would pass in the path variable (and convert it) into checkUserId method.

For example, if the URL were /user/123/resource, then the id passed in would be 123.

Method security is a bit more complicated than a simple allow or deny rule. Spring Security 3.0 introduced some new annotations in order to allow comprehensive support for the use of expressions.

There are four annotations which support expression attributes to allow pre and post-invocation authorization checks and also to support filtering of submitted collection arguments or return values.

They are @PreAuthorize, @PreFilter, @PostAuthorize and @PostFilter.

Their use is enabled through the global-method-security namespace element:

<global-method-security pre-post-annotations="enabled"/>

The most obviously useful annotation is @PreAuthorize which decides whether a method can actually be invoked or not.

For example (from the"Contacts" sample application)

@PreAuthorize("hasRole('USER')") public void create(Contact contact);

which means that access will only be allowed for users with the role "ROLE_USER". Obviously the same thing could easily be achieved using a traditional configuration and a simple configuration attribute for the required role. But what about:

@PreAuthorize("hasPermission(#contact, 'admin')") public void deletePermission(Contact contact, Sid recipient, Permission permission);

Here we’re actually using a method argument as part of the expression to decide whether the current user has the "admin"permission for the given contact.

The built-in hasPermission() expression is linked into the Spring Security ACL module through the application context, as we’llsee below.

You can access any of the method arguments by name as expression variables.

There are a number of ways in which Spring Security can resolve the method arguments.

Spring Security uses DefaultSecurityParameterNameDiscoverer to discover the parameter names.

By default, the following options are tried for a method as a whole.

-

If Spring Security’s

@Pannotation is present on a single argument to the method, the value will be used. This is useful for interfaces compiled with a JDK prior to JDK 8 which do not contain any information about the parameter names. For example:import org.springframework.security.access.method.P; ... @PreAuthorize("#c.name == authentication.name") public void doSomething(@P("c") Contact contact);

Behind the scenes this use implemented using

AnnotationParameterNameDiscovererwhich can be customized to support the value attribute of any specified annotation. -

If Spring Data’s

@Paramannotation is present on at least one parameter for the method, the value will be used. This is useful for interfaces compiled with a JDK prior to JDK 8 which do not contain any information about the parameter names. For example:import org.springframework.data.repository.query.Param; ... @PreAuthorize("#n == authentication.name") Contact findContactByName(@Param("n") String name);

Behind the scenes this use implemented using

AnnotationParameterNameDiscovererwhich can be customized to support the value attribute of any specified annotation. - If JDK 8 was used to compile the source with the -parameters argument and Spring 4+ is being used, then the standard JDK reflection API is used to discover the parameter names. This works on both classes and interfaces.

- Last, if the code was compiled with the debug symbols, the parameter names will be discovered using the debug symbols. This will not work for interfaces since they do not have debug information about the parameter names. For interfaces, annotations or the JDK 8 approach must be used.

Any Spring-EL functionality is available within the expression, so you can also access properties on the arguments. For example, if you wanted a particular method to only allow access to a user whose username matched that of the contact, you could write

@PreAuthorize("#contact.name == authentication.name") public void doSomething(Contact contact);

Here we are accessing another built-in expression, authentication, which is the Authentication stored in the security context.

You can also access its "principal" property directly, using the expression principal.

The value will often be a UserDetails instance, so you might use an expression like principal.username or principal.enabled.

Less commonly, you may wish to perform an access-control check after the method has been invoked.

This can be achieved using the @PostAuthorize annotation.

To access the return value from a method, use the built-in name returnObject in the expression.

As you may already be aware, Spring Security supports filtering of collections and arrays and this can now be achieved using expressions. This is most commonly performed on the return value of a method. For example:

@PreAuthorize("hasRole('USER')") @PostFilter("hasPermission(filterObject, 'read') or hasPermission(filterObject, 'admin')") public List<Contact> getAll();

When using the @PostFilter annotation, Spring Security iterates through the returned collection and removes any elements for which the supplied expression is false.

The name filterObject refers to the current object in the collection.

You can also filter before the method call, using @PreFilter, though this is a less common requirement.

The syntax is just the same, but if there is more than one argument which is a collection type then you have to select one by name using the filterTarget property of this annotation.

Note that filtering is obviously not a substitute for tuning your data retrieval queries. If you are filtering large collections and removing many of the entries then this is likely to be inefficient.

There are some built-in expressions which are specific to method security, which we have already seen in use above.

The filterTarget and returnValue values are simple enough, but the use of the hasPermission() expression warrants a closer look.

hasPermission() expressions are delegated to an instance of PermissionEvaluator.

It is intended to bridge between the expression system and Spring Security’s ACL system, allowing you to specify authorization constraints on domain objects, based on abstract permissions.

It has no explicit dependencies on the ACL module, so you could swap that out for an alternative implementation if required.

The interface has two methods:

boolean hasPermission(Authentication authentication, Object targetDomainObject, Object permission); boolean hasPermission(Authentication authentication, Serializable targetId, String targetType, Object permission);

which map directly to the available versions of the expression, with the exception that the first argument (the Authentication object) is not supplied.

The first is used in situations where the domain object, to which access is being controlled, is already loaded.

Then expression will return true if the current user has the given permission for that object.

The second version is used in cases where the object is not loaded, but its identifier is known.

An abstract "type" specifier for the domain object is also required, allowing the correct ACL permissions to be loaded.

This has traditionally been the Java class of the object, but does not have to be as long as it is consistent with how the permissions are loaded.

To use hasPermission() expressions, you have to explicitly configure a PermissionEvaluator in your application context.

This would look something like this:

<security:global-method-security pre-post-annotations="enabled"> <security:expression-handler ref="expressionHandler"/> </security:global-method-security> <bean id="expressionHandler" class= "org.springframework.security.access.expression.method.DefaultMethodSecurityExpressionHandler"> <property name="permissionEvaluator" ref="myPermissionEvaluator"/> </bean>

Where myPermissionEvaluator is the bean which implements PermissionEvaluator.

Usually this will be the implementation from the ACL module which is called AclPermissionEvaluator.

See the "Contacts" sample application configuration for more details.

You can make use of meta annotations for method security to make your code more readable. This is especially convenient if you find that you are repeating the same complex expression throughout your code base. For example, consider the following:

@PreAuthorize("#contact.name == authentication.name")

Instead of repeating this everywhere, we can create a meta annotation that can be used instead.

@Retention(RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME) @PreAuthorize("#contact.name == authentication.name") public @interface ContactPermission {}

Meta annotations can be used for any of the Spring Security method security annotations. In order to remain compliant with the specification JSR-250 annotations do not support meta annotations.

Our examples have only required users to be authenticated and have done so for every URL in our application.

We can specify custom requirements for our URLs by adding multiple children to our http.authorizeRequests() method.

For example:

protected void configure(HttpSecurity http) throws Exception { http .authorizeRequests(authorizeRequests ->authorizeRequests .antMatchers("/resources/**", "/signup", "/about").permitAll()

.antMatchers("/admin/**").hasRole("ADMIN")

.antMatchers("/db/**").access("hasRole('ADMIN') and hasRole('DBA')")

.anyRequest().authenticated()

) .formLogin(withDefaults()); }

|

There are multiple children to the | |

|

We specified multiple URL patterns that any user can access. Specifically, any user can access a request if the URL starts with "/resources/", equals "/signup", or equals "/about". | |

|

Any URL that starts with "/admin/" will be restricted to users who have the role "ROLE_ADMIN".

You will notice that since we are invoking the | |

|

Any URL that starts with "/db/" requires the user to have both "ROLE_ADMIN" and "ROLE_DBA".

You will notice that since we are using the | |

|

Any URL that has not already been matched on only requires that the user be authenticated |

From version 2.0 onwards Spring Security has improved support substantially for adding security to your service layer methods.

It provides support for JSR-250 annotation security as well as the framework’s original @Secured annotation.

From 3.0 you can also make use of new expression-based annotations.

You can apply security to a single bean, using the intercept-methods element to decorate the bean declaration, or you can secure multiple beans across the entire service layer using the AspectJ style pointcuts.

We can enable annotation-based security using the @EnableGlobalMethodSecurity annotation on any @Configuration instance.

For example, the following would enable Spring Security’s @Secured annotation.

@EnableGlobalMethodSecurity(securedEnabled = true) public class MethodSecurityConfig { // ... }

Adding an annotation to a method (on a class or interface) would then limit the access to that method accordingly. Spring Security’s native annotation support defines a set of attributes for the method. These will be passed to the AccessDecisionManager for it to make the actual decision:

public interface BankService { @Secured("IS_AUTHENTICATED_ANONYMOUSLY") public Account readAccount(Long id); @Secured("IS_AUTHENTICATED_ANONYMOUSLY") public Account[] findAccounts(); @Secured("ROLE_TELLER") public Account post(Account account, double amount); }

Support for JSR-250 annotations can be enabled using

@EnableGlobalMethodSecurity(jsr250Enabled = true) public class MethodSecurityConfig { // ... }

These are standards-based and allow simple role-based constraints to be applied but do not have the power Spring Security’s native annotations. To use the new expression-based syntax, you would use

@EnableGlobalMethodSecurity(prePostEnabled = true) public class MethodSecurityConfig { // ... }

and the equivalent Java code would be

public interface BankService { @PreAuthorize("isAnonymous()") public Account readAccount(Long id); @PreAuthorize("isAnonymous()") public Account[] findAccounts(); @PreAuthorize("hasAuthority('ROLE_TELLER')") public Account post(Account account, double amount); }

Sometimes you may need to perform operations that are more complicated than are possible with the @EnableGlobalMethodSecurity annotation allow.

For these instances, you can extend the GlobalMethodSecurityConfiguration ensuring that the @EnableGlobalMethodSecurity annotation is present on your subclass.

For example, if you wanted to provide a custom MethodSecurityExpressionHandler, you could use the following configuration:

@EnableGlobalMethodSecurity(prePostEnabled = true) public class MethodSecurityConfig extends GlobalMethodSecurityConfiguration { @Override protected MethodSecurityExpressionHandler createExpressionHandler() { // ... create and return custom MethodSecurityExpressionHandler ... return expressionHandler; } }

For additional information about methods that can be overridden, refer to the GlobalMethodSecurityConfiguration Javadoc.

This element is used to enable annotation-based security in your application (by setting the appropriate attributes on the element), and also to group together security pointcut declarations which will be applied across your entire application context.

You should only declare one <global-method-security> element.

The following declaration would enable support for Spring Security’s @Secured:

<global-method-security secured-annotations="enabled" />

Adding an annotation to a method (on an class or interface) would then limit the access to that method accordingly.

Spring Security’s native annotation support defines a set of attributes for the method.

These will be passed to the AccessDecisionManager for it to make the actual decision:

public interface BankService { @Secured("IS_AUTHENTICATED_ANONYMOUSLY") public Account readAccount(Long id); @Secured("IS_AUTHENTICATED_ANONYMOUSLY") public Account[] findAccounts(); @Secured("ROLE_TELLER") public Account post(Account account, double amount); }

Support for JSR-250 annotations can be enabled using

<global-method-security jsr250-annotations="enabled" />

These are standards-based and allow simple role-based constraints to be applied but do not have the power Spring Security’s native annotations. To use the new expression-based syntax, you would use

<global-method-security pre-post-annotations="enabled" />

and the equivalent Java code would be

public interface BankService { @PreAuthorize("isAnonymous()") public Account readAccount(Long id); @PreAuthorize("isAnonymous()") public Account[] findAccounts(); @PreAuthorize("hasAuthority('ROLE_TELLER')") public Account post(Account account, double amount); }

Expression-based annotations are a good choice if you need to define simple rules that go beyond checking the role names against the user’s list of authorities.

![[Note]](images/note.png) | Note |

|---|---|

|

===

The annotated methods will only be secured for instances which are defined as Spring beans (in the same application context in which method-security is enabled).

If you want to secure instances which are not created by Spring (using the |

![[Note]](images/note.png) | Note |

|---|---|

|

=== You can enable more than one type of annotation in the same application, but only one type should be used for any interface or class as the behaviour will not be well-defined otherwise. If two annotations are found which apply to a particular method, then only one of them will be applied. === |

The use of protect-pointcut is particularly powerful, as it allows you to apply security to many beans with only a simple declaration.

Consider the following example:

<global-method-security> <protect-pointcut expression="execution(* com.mycompany.*Service.*(..))" access="ROLE_USER"/> </global-method-security>

This will protect all methods on beans declared in the application context whose classes are in the com.mycompany package and whose class names end in "Service".

Only users with the ROLE_USER role will be able to invoke these methods.

As with URL matching, the most specific matches must come first in the list of pointcuts, as the first matching expression will be used.

Security annotations take precedence over pointcuts.

Complex applications often will find the need to define access permissions not simply at a web request or method invocation level.

Instead, security decisions need to comprise both who (Authentication), where (MethodInvocation) and what (SomeDomainObject).

In other words, authorization decisions also need to consider the actual domain object instance subject of a method invocation.

Imagine you’re designing an application for a pet clinic. There will be two main groups of users of your Spring-based application: staff of the pet clinic, as well as the pet clinic’s customers. The staff will have access to all of the data, whilst your customers will only be able to see their own customer records. To make it a little more interesting, your customers can allow other users to see their customer records, such as their "puppy preschool" mentor or president of their local "Pony Club". Using Spring Security as the foundation, you have several approaches that can be used:

-

Write your business methods to enforce the security.

You could consult a collection within the

Customerdomain object instance to determine which users have access. By using theSecurityContextHolder.getContext().getAuthentication(), you’ll be able to access theAuthenticationobject. -

Write an

AccessDecisionVoterto enforce the security from theGrantedAuthority[]s stored in theAuthenticationobject. This would mean yourAuthenticationManagerwould need to populate theAuthenticationwith customGrantedAuthority[]s representing each of theCustomerdomain object instances the principal has access to. -

Write an

AccessDecisionVoterto enforce the security and open the targetCustomerdomain object directly. This would mean your voter needs access to a DAO that allows it to retrieve theCustomerobject. It would then access theCustomerobject’s collection of approved users and make the appropriate decision.

Each one of these approaches is perfectly legitimate.

However, the first couples your authorization checking to your business code.

The main problems with this include the enhanced difficulty of unit testing and the fact it would be more difficult to reuse the Customer authorization logic elsewhere.

Obtaining the GrantedAuthority[] s from the Authentication object is also fine, but will not scale to large numbers of Customer s.

If a user might be able to access 5,000 Customer s (unlikely in this case, but imagine if it were a popular vet for a large Pony Club!) the amount of memory consumed and time required to construct the Authentication object would be undesirable.

The final method, opening the Customer directly from external code, is probably the best of the three.

It achieves separation of concerns, and doesn’t misuse memory or CPU cycles, but it is still inefficient in that both the AccessDecisionVoter and the eventual business method itself will perform a call to the DAO responsible for retrieving the Customer object.

Two accesses per method invocation is clearly undesirable.

In addition, with every approach listed you’ll need to write your own access control list (ACL) persistence and business logic from scratch.

Fortunately, there is another alternative, which we’ll talk about below.

Spring Security’s ACL services are shipped in the spring-security-acl-xxx.jar.

You will need to add this JAR to your classpath to use Spring Security’s domain object instance security capabilities.

Spring Security’s domain object instance security capabilities centre on the concept of an access control list (ACL). Every domain object instance in your system has its own ACL, and the ACL records details of who can and can’t work with that domain object. With this in mind, Spring Security delivers three main ACL-related capabilities to your application:

- A way of efficiently retrieving ACL entries for all of your domain objects (and modifying those ACLs)

- A way of ensuring a given principal is permitted to work with your objects, before methods are called

- A way of ensuring a given principal is permitted to work with your objects (or something they return), after methods are called

As indicated by the first bullet point, one of the main capabilities of the Spring Security ACL module is providing a high-performance way of retrieving ACLs. This ACL repository capability is extremely important, because every domain object instance in your system might have several access control entries, and each ACL might inherit from other ACLs in a tree-like structure (this is supported out-of-the-box by Spring Security, and is very commonly used). Spring Security’s ACL capability has been carefully designed to provide high performance retrieval of ACLs, together with pluggable caching, deadlock-minimizing database updates, independence from ORM frameworks (we use JDBC directly), proper encapsulation, and transparent database updating.

Given databases are central to the operation of the ACL module, let’s explore the four main tables used by default in the implementation. The tables are presented below in order of size in a typical Spring Security ACL deployment, with the table with the most rows listed last:

-

ACL_SID allows us to uniquely identify any principal or authority in the system ("SID" stands for "security identity").

The only columns are the ID, a textual representation of the SID, and a flag to indicate whether the textual representation refers to a principal name or a

GrantedAuthority. Thus, there is a single row for each unique principal orGrantedAuthority. When used in the context of receiving a permission, a SID is generally called a "recipient". - ACL_CLASS allows us to uniquely identify any domain object class in the system. The only columns are the ID and the Java class name. Thus, there is a single row for each unique Class we wish to store ACL permissions for.

- ACL_OBJECT_IDENTITY stores information for each unique domain object instance in the system. Columns include the ID, a foreign key to the ACL_CLASS table, a unique identifier so we know which ACL_CLASS instance we’re providing information for, the parent, a foreign key to the ACL_SID table to represent the owner of the domain object instance, and whether we allow ACL entries to inherit from any parent ACL. We have a single row for every domain object instance we’re storing ACL permissions for.

- Finally, ACL_ENTRY stores the individual permissions assigned to each recipient. Columns include a foreign key to the ACL_OBJECT_IDENTITY, the recipient (ie a foreign key to ACL_SID), whether we’ll be auditing or not, and the integer bit mask that represents the actual permission being granted or denied. We have a single row for every recipient that receives a permission to work with a domain object.

As mentioned in the last paragraph, the ACL system uses integer bit masking.

Don’t worry, you need not be aware of the finer points of bit shifting to use the ACL system, but suffice to say that we have 32 bits we can switch on or off.

Each of these bits represents a permission, and by default the permissions are read (bit 0), write (bit 1), create (bit 2), delete (bit 3) and administer (bit 4).

It’s easy to implement your own Permission instance if you wish to use other permissions, and the remainder of the ACL framework will operate without knowledge of your extensions.

It is important to understand that the number of domain objects in your system has absolutely no bearing on the fact we’ve chosen to use integer bit masking. Whilst you have 32 bits available for permissions, you could have billions of domain object instances (which will mean billions of rows in ACL_OBJECT_IDENTITY and quite probably ACL_ENTRY). We make this point because we’ve found sometimes people mistakenly believe they need a bit for each potential domain object, which is not the case.

Now that we’ve provided a basic overview of what the ACL system does, and what it looks like at a table structure, let’s explore the key interfaces. The key interfaces are:

-

Acl: Every domain object has one and only oneAclobject, which internally holds theAccessControlEntrys as well as knows the owner of theAcl. An Acl does not refer directly to the domain object, but instead to anObjectIdentity. TheAclis stored in the ACL_OBJECT_IDENTITY table. -

AccessControlEntry: AnAclholds multipleAccessControlEntrys, which are often abbreviated as ACEs in the framework. Each ACE refers to a specific tuple ofPermission,SidandAcl. An ACE can also be granting or non-granting and contain audit settings. The ACE is stored in the ACL_ENTRY table. -

Permission: A permission represents a particular immutable bit mask, and offers convenience functions for bit masking and outputting information. The basic permissions presented above (bits 0 through 4) are contained in theBasePermissionclass. -

Sid: The ACL module needs to refer to principals andGrantedAuthority[]s. A level of indirection is provided by theSidinterface, which is an abbreviation of "security identity". Common classes includePrincipalSid(to represent the principal inside anAuthenticationobject) andGrantedAuthoritySid. The security identity information is stored in the ACL_SID table. -

ObjectIdentity: Each domain object is represented internally within the ACL module by anObjectIdentity. The default implementation is calledObjectIdentityImpl. -

AclService: Retrieves theAclapplicable for a givenObjectIdentity. In the included implementation (JdbcAclService), retrieval operations are delegated to aLookupStrategy. TheLookupStrategyprovides a highly optimized strategy for retrieving ACL information, using batched retrievals(BasicLookupStrategy) and supporting custom implementations that leverage materialized views, hierarchical queries and similar performance-centric, non-ANSI SQL capabilities. -

MutableAclService: Allows a modifiedAclto be presented for persistence. It is not essential to use this interface if you do not wish.

Please note that our out-of-the-box AclService and related database classes all use ANSI SQL. This should therefore work with all major databases. At the time of writing, the system had been successfully tested using Hypersonic SQL, PostgreSQL, Microsoft SQL Server and Oracle.

Two samples ship with Spring Security that demonstrate the ACL module. The first is the Contacts Sample, and the other is the Document Management System (DMS) Sample. We suggest taking a look over these for examples.

To get starting using Spring Security’s ACL capability, you will need to store your ACL information somewhere.

This necessitates the instantiation of a DataSource using Spring.

The DataSource is then injected into a JdbcMutableAclService and BasicLookupStrategy instance.

The latter provides high-performance ACL retrieval capabilities, and the former provides mutator capabilities.

Refer to one of the samples that ship with Spring Security for an example configuration.

You’ll also need to populate the database with the four ACL-specific tables listed in the last section (refer to the ACL samples for the appropriate SQL statements).

Once you’ve created the required schema and instantiated JdbcMutableAclService, you’ll next need to ensure your domain model supports interoperability with the Spring Security ACL package.

Hopefully ObjectIdentityImpl will prove sufficient, as it provides a large number of ways in which it can be used.

Most people will have domain objects that contain a public Serializable getId() method.

If the return type is long, or compatible with long (eg an int), you will find you need not give further consideration to ObjectIdentity issues.

Many parts of the ACL module rely on long identifiers.

If you’re not using long (or an int, byte etc), there is a very good chance you’ll need to reimplement a number of classes.

We do not intend to support non-long identifiers in Spring Security’s ACL module, as longs are already compatible with all database sequences, the most common identifier data type, and are of sufficient length to accommodate all common usage scenarios.

The following fragment of code shows how to create an Acl, or modify an existing Acl:

// Prepare the information we'd like in our access control entry (ACE) ObjectIdentity oi = new ObjectIdentityImpl(Foo.class, new Long(44)); Sid sid = new PrincipalSid("Samantha"); Permission p = BasePermission.ADMINISTRATION; // Create or update the relevant ACL MutableAcl acl = null; try { acl = (MutableAcl) aclService.readAclById(oi); } catch (NotFoundException nfe) { acl = aclService.createAcl(oi); } // Now grant some permissions via an access control entry (ACE) acl.insertAce(acl.getEntries().length, p, sid, true); aclService.updateAcl(acl);

In the example above, we’re retrieving the ACL associated with the "Foo" domain object with identifier number 44. We’re then adding an ACE so that a principal named "Samantha" can "administer" the object. The code fragment is relatively self-explanatory, except the insertAce method. The first argument to the insertAce method is determining at what position in the Acl the new entry will be inserted. In the example above, we’re just putting the new ACE at the end of the existing ACEs. The final argument is a Boolean indicating whether the ACE is granting or denying. Most of the time it will be granting (true), but if it is denying (false), the permissions are effectively being blocked.

Spring Security does not provide any special integration to automatically create, update or delete ACLs as part of your DAO or repository operations. Instead, you will need to write code like shown above for your individual domain objects. It’s worth considering using AOP on your services layer to automatically integrate the ACL information with your services layer operations. We’ve found this quite an effective approach in the past.

Once you’ve used the above techniques to store some ACL information in the database, the next step is to actually use the ACL information as part of authorization decision logic.

You have a number of choices here.

You could write your own AccessDecisionVoter or AfterInvocationProvider that respectively fires before or after a method invocation.

Such classes would use AclService to retrieve the relevant ACL and then call Acl.isGranted(Permission[] permission, Sid[] sids, boolean administrativeMode) to decide whether permission is granted or denied.

Alternately, you could use our AclEntryVoter, AclEntryAfterInvocationProvider or AclEntryAfterInvocationCollectionFilteringProvider classes.

All of these classes provide a declarative-based approach to evaluating ACL information at runtime, freeing you from needing to write any code.

Please refer to the sample applications to learn how to use these classes.