Running a Job

At a minimum, launching a batch job requires two things: the

Job to be launched and a

JobOperator. Both can be contained within the same

context or different contexts. For example, if you launch jobs from the

command line, a new JVM is instantiated for each Job. Thus, every

job has its own JobOperator. However, if

you run from within a web container that is within the scope of an

HttpRequest, there is usually one

JobOperator (configured for asynchronous job

launching) that multiple requests invoke to launch their jobs.

Running Jobs from the Command Line

If you want to run your jobs from an enterprise

scheduler, the command line is the primary interface. This is because

most schedulers (with the exception of Quartz, unless using

NativeJob) work directly with operating system

processes, primarily kicked off with shell scripts. There are many ways

to launch a Java process besides a shell script, such as Perl, Ruby, or

even build tools, such as Ant or Maven. However, because most people

are familiar with shell scripts, this example focuses on them.

The CommandLineJobOperator

Because the script launching the job must kick off a Java

Virtual Machine, there needs to be a class with a main method to act

as the primary entry point. Spring Batch provides an implementation

that serves this purpose:

CommandLineJobOperator. Note

that this is just one way to bootstrap your application. There are

many ways to launch a Java process, and this class should in no way be

viewed as definitive. The CommandLineJobOperator

performs four tasks:

-

Load the appropriate

ApplicationContext. -

Parse command line arguments into

JobParameters. -

Locate the appropriate job based on arguments.

-

Use the

JobOperatorprovided in the application context to launch the job.

All of these tasks are accomplished with only the arguments passed in. The following table describes the required arguments:

|

The fully qualified name of the job configuration class used to

create an |

|

The name of the operation to execute on the job. Can be one of [ |

|

Depending on the operation, this can be the name of the job to start or the execution ID of the job to stop, restart, abandon or recover. |

When starting a job, all arguments after these are considered to be job parameters, are turned into a JobParameters object,

and must be in the format of name=value,type,identifying. In the case of stopping, restarting, abandoning or recovering a job, the jobExecutionId is

expected as the 4th argument, and all remaining arguments are ignored.

The following example shows a date passed as a job parameter to a job defined in Java:

<bash$ java CommandLineJobOperator io.spring.EndOfDayJobConfiguration start endOfDay schedule.date=2007-05-05,java.time.LocalDateBy default, the CommandLineJobOperator uses a DefaultJobParametersConverter that implicitly converts

key/value pairs to identifying job parameters. However, you can explicitly specify

which job parameters are identifying and which are not by suffixing them with true or false, respectively.

In the following example, schedule.date is an identifying job parameter, while vendor.id is not:

<bash$ java CommandLineJobOperator io.spring.EndOfDayJobConfiguration start endOfDay \

schedule.date=2007-05-05,java.time.LocalDate,true \

vendor.id=123,java.lang.Long,falseYou can override this behavior by setting a custom JobParametersConverter on the CommandLineJobOperator.

Exit Codes

When launching a batch job from the command-line, an enterprise

scheduler is often used. Most schedulers are fairly dumb and work only

at the process level. This means that they only know about some

operating system process (such as a shell script that they invoke).

In this scenario, the only way to communicate back to the scheduler

about the success or failure of a job is through return codes. A

return code is a number that is returned to a scheduler by the process

to indicate the result of the run. In the simplest case, 0 is

success and 1 is failure. However, there may be more complex

scenarios, such as “If job A returns 4, kick off job B, and, if it returns 5, kick

off job C.” This type of behavior is configured at the scheduler level,

but it is important that a processing framework such as Spring Batch

provide a way to return a numeric representation of the exit code

for a particular batch job. In Spring Batch, this is encapsulated

within an ExitStatus, which is covered in more

detail in Chapter 5. For the purposes of discussing exit codes, the

only important thing to know is that an

ExitStatus has an exit code property that is

set by the framework (or the developer) and is returned as part of the

JobExecution returned from the JobOperator. The

CommandLineJobOperator converts this string value

to a number by using the ExitCodeMapper

interface:

public interface ExitCodeMapper {

int intValue(String exitCode);

}The essential contract of an ExitCodeMapper is that, given a string exit

code, a number representation will be returned. The default implementation

used by the job runner is the SimpleJvmExitCodeMapper

that returns 0 for completion, 1 for generic errors, and 2 for any job

runner errors such as not being able to find a

Job in the provided context. If anything more

complex than the three values above is needed, a custom

implementation of the ExitCodeMapper interface

must be supplied by setting it on the CommandLineJobOperator.

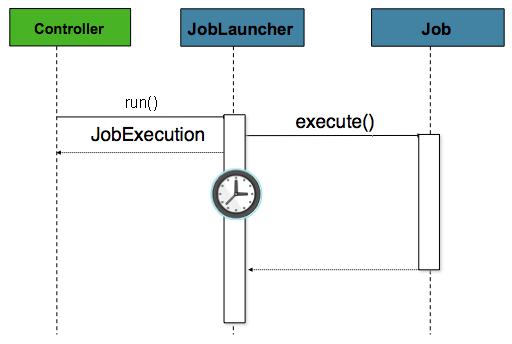

Running Jobs from within a Web Container

Historically, offline processing (such as batch jobs) has been

launched from the command-line, as described earlier. However, there are

many cases where launching from an HttpRequest is

a better option. Many such use cases include reporting, ad-hoc job

running, and web application support. Because a batch job (by definition)

is long running, the most important concern is to launch the

job asynchronously:

The controller in this case is a Spring MVC controller. See the

Spring Framework Reference Guide for more about Spring MVC.

The controller launches a Job by using a

JobOperator that has been configured to launch

asynchronously, which

immediately returns a JobExecution. The

Job is likely still running. However, this

nonblocking behavior lets the controller return immediately, which

is required when handling an HttpRequest. The following listing

shows an example:

@Controller

public class JobOperatorController {

@Autowired

JobOperator jobOperator;

@Autowired

Job job;

@RequestMapping("/jobOperator.html")

public void handle() throws Exception{

jobOperator.start(job, new JobParameters());

}

}